“Turbulent visions of a vengeful God, doomed sinners, and prophets crying in the wilderness…tragic, violent narratives of crime and punishment…hangings, plagues, propitiations, and beheadings,”–all appear in the twelve panels in the center of the Sistine Chapel ceiling.

In his masterful portrayal of Michelangelo’s four-year effort to fill the 12,000 square foot, vaulted ceiling of the Sistine Chapel with new frescoes for Pope Julius II, a commission Michelangelo had tried to avoid, Ross King examines and places in context the known details of Michelangelo’s life, the images he includes in the frescoes, and his relationship with Pope Julius II, called the “terrifying Pope,” a man who is thought, ironically, to have been much like Michelangelo himself in personality. This was a tumultuous and monumental era artistically, one in which Pope Julius II tore down the existing St. Peter’s Basilica and started a completely new cathedral, created new papal apartments and a library, planned an immense tomb for himself, and determined to have the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel frescoed in a way which would confer even greater status upon himself and the church. This vibrant and exciting atmosphere offered Michelangelo and his contemporaries many opportunities for work, but competition was fierce, artists were always at the mercy of their patrons, and they didn’t have much, if any, choice in their subject matter, a fact that author King stresses in the book’s title.

In his masterful portrayal of Michelangelo’s four-year effort to fill the 12,000 square foot, vaulted ceiling of the Sistine Chapel with new frescoes for Pope Julius II, a commission Michelangelo had tried to avoid, Ross King examines and places in context the known details of Michelangelo’s life, the images he includes in the frescoes, and his relationship with Pope Julius II, called the “terrifying Pope,” a man who is thought, ironically, to have been much like Michelangelo himself in personality. This was a tumultuous and monumental era artistically, one in which Pope Julius II tore down the existing St. Peter’s Basilica and started a completely new cathedral, created new papal apartments and a library, planned an immense tomb for himself, and determined to have the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel frescoed in a way which would confer even greater status upon himself and the church. This vibrant and exciting atmosphere offered Michelangelo and his contemporaries many opportunities for work, but competition was fierce, artists were always at the mercy of their patrons, and they didn’t have much, if any, choice in their subject matter, a fact that author King stresses in the book’s title.

Michelangelo was a sculptor, not a painter, and he was angry at Pope Julius II for commissioning him to design and build the Pope’s tomb in 1507, and then abandoning the project it in favor of the Sistine Chapel after Michelangelo had bought all the marble. He was unpracticed with the technique of fresco, having never worked in it before. When the inexperienced Michelangelo finally accepted the commission and began work on the Sistine Chapel in 1508, his first panel was ruined by the build-up of salts and efflorescence on the surface of the painting, and when he worked with a too-wet surface, mold and mildew developed, discoloring his fresco. Michelangelo had to chip away the entire fresco in order to correct his mistakes in one section, a section which had taken him six weeks to create.

Michelangelo was a sculptor, not a painter, and he was angry at Pope Julius II for commissioning him to design and build the Pope’s tomb in 1507, and then abandoning the project it in favor of the Sistine Chapel after Michelangelo had bought all the marble. He was unpracticed with the technique of fresco, having never worked in it before. When the inexperienced Michelangelo finally accepted the commission and began work on the Sistine Chapel in 1508, his first panel was ruined by the build-up of salts and efflorescence on the surface of the painting, and when he worked with a too-wet surface, mold and mildew developed, discoloring his fresco. Michelangelo had to chip away the entire fresco in order to correct his mistakes in one section, a section which had taken him six weeks to create.

The Temptation and Expulsion of Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden

Designing the ceiling to tell the stories of Genesis in the Old Testament in the brightest and costliest pigments possible, Michelangelo depicted subjects like the Sacrifice of Noah, the Temptation and Expulsion, and the Creation of Eve, powerful visions of a terrifying God, “undoubtedly part of Savonarola’s legacy.” In Florence, Savonarola drew huge crowds with his fire-and-brimstone sermons. By October 1512, however, Michelangelo had been working on the Sistine Chapel ceiling for four arduous years. In a letter to his father, who had written from Florence asking for money, he wrote: “I lead a miserable existence. I live wearied by stupendous labours and beset by a thousand anxieties. And thus have I lived for some fifteen years [as an artist] and never an hour’s happiness have I had.

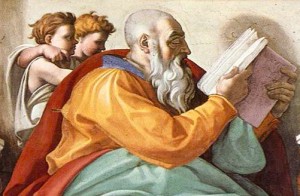

Michelangelo’s Zechariah, a portrait of Pope Julius II, shows him with a child behind, making the obscene gesture, the “sign of the fig.”

Because the megalomaniacal Pope Julius saw himself as a “messianic agent of the Lord,” Michelangelo incorporated several portraits of Julius in the ceiling, one of them as the prophet Zechariah. (One of the children behind Zechariah is making an obscene gesture.) He portrayed himself as the beheaded Holofernes, whose head is carried by Judith. Five sybils from Greek mythology appear alongside the prophets of the Bible, and twenty-five women are included among the ancestors of Jesus, an unusual consideration in this male society. Most striking are twenty, six-foot high nude male figures in dramatic poses, flanking five of the Genesis scenes.

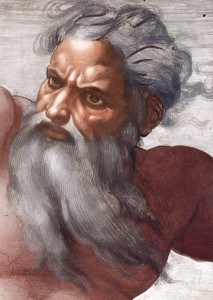

The Creation of Adam, showing God’s upper chest bare, and his legs below the thigh bare, a new concept of the divinity.

A year long hiatus occurred between the first and second halves of this commission, and it was then, when the scaffolding was removed for the first time, that Michelangelo could see his frescoes from the floor, as a viewer would. He decided that his first panels were too “busy,” with too many figures painted too small to carry the impact he wanted. When he resumed work on the second half of the ceiling, beginning with the Creation of Adam, he painted much simpler designs, with larger figures, dramatically foreshortened and contorted. The stunning differences between the first six panels and the last six are seen particularly in the appearance of God. In the early panels, he appears in classical attire, formal and fully robed; in the later panels he is far more vigorous, muscular, and “human” in appearance. In the “Creation of Adam,” for example, his upper chest is bare, and he is reclining, as he touches Adam with his finger. In the final panels, God is so dramatically foreshortened that he seems to be leaning down into the chapel, ready “to tumble [down] toward the viewer.”

New, realistic depiction of God’s face and body in The Creation of the Sun and Moon.

Despite his difficulties with the Pope, with the medium, and with the four years the painting took from his life, Michelangelo was ultimately able to achieve the sublime and do so in ways which would revolutionize painting forever. Vasari commented that “When the work was thrown open [in 1512], the whole world could be heard running up to see it, and, indeed, it was such as to make everyone astonished and dumb.” The power and grace of his figures were said to surpass those of the ancient Greeks. “Never before, in either marble or paint, had the expressive possibilities of the human form been detailed with such astonishing invention and aplomb…or with the brute visual force of Michelangelo’s naked titans.”

Overall picture of ceiling, with the Creation of Adam in the center and the Creation of the Sun and the Moon in the bottom center.

Author King’s careful analysis of individual panels and details shed light on who the various Biblical characters are, the stories associated with them, their significance to the audience of the day, and their merits as individual works of art. His text is full of memorable details – including how Michelangelo constructed the scaffold for the fresco (which did not require him to lie on his back) and the fact that the fingers of God and Adam at the Creation, one of the most famous of the fresco’s images, are not the work of Michelangelo or of his assistants but are complete restorations. Well researched and written with enthusiasm, Michelangelo and the Pope’s Ceiling is a fascinating story about one of the world’s most important artworks, a work which is as fresh and as captivating today as it was when it was painted almost six hundred years ago. Anyone with an iota of interest in art history should find this highly readable piece of scholarship a can’t-put-it-downer.

ALSO by Ross King: LEONARDO AND THE LAST SUPPER, BRUNELLESCHI’S DOME: How a Renaissance Genius Reinvented Architecture, MAD ENCHANTMENT: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on http://www.thestar.com

The Temptation and Expulsion of Adam and Eve is from http://www.studyblue.com

The depiction of Zechariah, with the face of Pope Julius II, appears on http://sistinepuzzle.com

The Creation of Adam may be found on http://usao.edu/

God, as seen in the Creation of the Sun and the Moon is from http://commons.wikimedia.org

The overview of the Sistine Chapel ceiling appears on http://www.visitingdc.com