“What made [Santamaria] stand out from all the other healers who swarmed in the valley was his scorpion tea. “Drink it down all at once,” he would say, “and you’ll see your vigor return and tackle whatever confronts you.” – from “The Scarab’s Revenge.”

Poet-author Serge Pey, the child of Republican partisans and anarchists who participated in the Spanish Civil War, knows well the stories of this terrible civil war and the horrors of defeat.

Poet-author Serge Pey, the child of Republican partisans and anarchists who participated in the Spanish Civil War, knows well the stories of this terrible civil war and the horrors of defeat.

Author Pey, born in 1950, ten years after the war ended, grew up in the internment camps of France, to which his parents, like those of many other defeated Spanish fighters, escaped in the aftermath of the war. Confined to these rough camps as soon as they were captured, they were treated like the criminals the Franco government and much of France considered them to be. Within the camps, they were always at risk of being identified by powerful Spanish Fascists and Nationalists, out for revenge for their past “war crimes,” and they expected, and often observed, torture and executions if their past crimes, atrocities, real names – were ever discovered. Despite the dangers, however, they still believed in themselves and in the freedom for which they had fought and lost. Here in this collection of often interconnected stories, Serge Pey provides glimpses of a unique and powerful culture, stories of the lives of his family and their friends during and immediately after the Spanish Civil War.

Pey’s prose and his poetry combine within these stories, filled with images and events of a harsh reality, at the same time that the characters’ hopes for a happy life filled with meaning also live large. Though some might say that some stories even contain elements of “magic realism,” I prefer to think that Pey is really describing the magic of a different reality from anything that these characters or their readers have ever known or expected – not a series of events that reflect the warm and fuzzy “magic realism” so common in current novels, but instead a reality in which some kind of magic emerges to make life worth living. In the first story, “An Execution,” a man and a young boy are tending a field when five members of the fascist gardia civil confront them, telling them that they have six hours to leave the farm. After they leave, the boy watches an eagle wheeling in the sky, helps the man gut and cook a piglet for food, and finds a shell, which the man tells him will “bring good luck because [shells] hold the voices of the departed.” The gardia returns to kill the man while the boy hides in a hole. In the final scene the imagery of the snail, the man’s ghost, the eagle, and the empty shell all take on new meaning – no magic realism, but a story so powerful that reality itself, as the boy faces the future, makes his situation more bearable.

“The Washing and the Clothes Line,” a first-person story of a mother and child, focuses on a woman whom all the neighbors consider to be crazy. Following a strict ritual, the mother puts out her laundry every day, and often does not take in. Sometimes she takes in some but not all pieces, and sometimes she moves it from the line to a field, or to some trees, or removes or adds a few other pieces. In the secret language with which she communicates with the mountain, she stays busy all day, and when the security police arrive and hide behind the cemetery wall, she recognizes the need to signal their presence to her allies who might have been watching, waiting for a chance to come down from the mountain. The mother has the boy put out his shirt, which flutters like a poor man’s flag, a laundry-based signal like all the others. “I was a semaphore unto myself,” he says, as the security police eventually leave. Later, when the woman grows older and lives in a small shack, she remembers when “freedom was built not with the mouth but with the hands,” as she continues to build her own freedom and preserve her sign language within the shack.

Other stories include “La Cega,” a blind woman who was a flesh and blood clock in the valley, one who believed that “watches injure time,” and that “some watches prefer to die so as to be still closer to the great time that circles above us.” “Cherry Thief” is the story of a young boy and an old “uncle,” who lets him eat cherries that he has grown, telling him that he is not eating cherries. “You are eating Guillermo Ganuza Navarro.” Every tree in the orchard is named for a man who was assassinated between 1949 and 1960, and he wants the boy to be sure to inscribe his name on the one remaining tree without a name when he himself is gone. Years pass, and eventually, he carves a name. “The Scarab’s Revenge” is a tale of scarab beetles, scarab jewelry, the art of concealing a scorpion inside a scarab, and the act of vengeance, which is “an art as difficult as the art of love…Vengeance is the highest form of forgiveness…and “getting revenge avoids a Mass.”

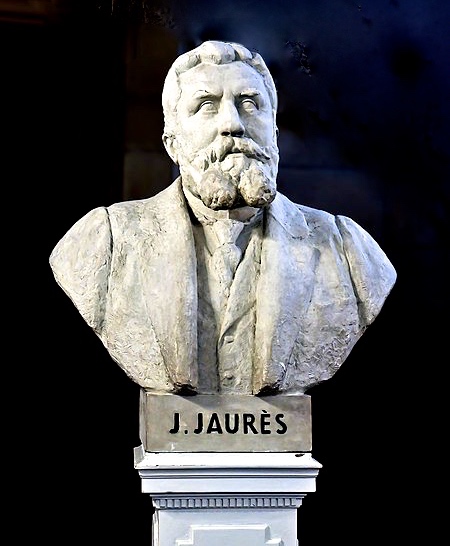

“The Piece of Wood” details the escape of a young boy, age twelve, inside a barrel which is being used to hide another body, leads to the story of how the boy lost his brother and sister in all the turmoil, his adoption of a puppy, and, horrifically, the demand of the director of the camp that he reveal names of people he knows, including his own family, and that he choose between saving his friend Pablo, who had been beaten bloody, and the life of his puppy. “The Treasure of the Spanish Civil War,” a story near the end of the collection, tells of a buried treasure which, many years later, the survivors of the war decide to dig up. For the main character, the most important thing to be discovered is the memory of the Way and how we transmit the memory of that special Way. “Do not go where the road may lead. Go where there is no road, and leave tracks.” “The Apostle of Peace,” refers to Jean Jaurès, a French socialist and anti-militarist, shot by an assassin named “Villain.” For the speaker, Jaurès becomes “a true beam, a light in the darkness of the great butchery of workers that was the First World War.” Filled with dramatic events, symbols, and hidden messages, this book is more than literary fiction. It is true literature, a collection of writings which inspire thoughtful reflection on life itself and share the ideas of its characters and author, a work which many readers will enjoy reading again and again and again.

Photos. The author’s photo appears on https://archipelagobooks.org

Eve Andersson’s photo of Clothes Drying on Trees, 2011, is from http://www.eveandersson.com

The French scorpion may be found on https://www.independent.ie/

The bust of Jean Jaurès is posted on https://commons.wikimedia.org

The snail shell is symbolic in “An Execution,” and appears on https://gallery.yopriceville.com