“I am an Iranian writer tired of writing dark and bitter stories, stories populated by ghosts and dead narrators with predictable endings of death and destruction. I am a writer who at the threshold of fifty has understood that the purportedly real world around us has enough death and destruction and sorrow, and that I did not have the right to add even more defeat and hopelessness to it with my stories.”

When I picked up this book, written by a Iranian author, my only expectation was that it would be an interesting view of life in Iran today, and, in particular, the life of a writer trying to avoid the “thought police.” What I never expected was that the book would be so funny! Witty, cleverly constructed, satiric, and full of the absurdities that always underlie great satire, Censoring an Iranian Love Story is a unique metafiction that draws in the reader, sits him down in the company of an immensely talented and very charming author, and completely enthralls him.

I picked up this book, written by a Iranian author, my only expectation was that it would be an interesting view of life in Iran today, and, in particular, the life of a writer trying to avoid the “thought police.” What I never expected was that the book would be so funny! Witty, cleverly constructed, satiric, and full of the absurdities that always underlie great satire, Censoring an Iranian Love Story is a unique metafiction that draws in the reader, sits him down in the company of an immensely talented and very charming author, and completely enthralls him.

The author, having reached the “threshold of fifty,” tells us at the outset that he intends to write a love story, one that is “a gateway to light. A story that, although it does not have a happy ending like romantic Hollywood movies, still has an ending that will not make my reader afraid of falling in love. And, of course, a story that cannot be political.” Most importantly, he says, “I want to publish my love story in my homeland.”

The author then becomes the narrator of two stories—a fictional love story, which appears here in boldface, and a metafictional commentary by the author of the love story, in regular type. Experimenting with what to include in his love story, what direction to take, and what he hopes to get away with when his story is read, the narrator, named, not surprisingly, “Shariar Mandanipour,” writes for the censor, ironically named Porfiry Petrovich, the police investigator of Raskolnikov in Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment. He thinks that “because I am an experienced writer, I may be able to write my story in such a way that it survives the blade of censorship.”

But the author is also true to his reader. Whenever he believes that Petrovich will reject something, he either crosses it out himself (leaving it visible so that the reader can read, literally, between the lines), or he changes direction and rewrites the action of the story, while explaining why Petrovich might object. He never rants or gets angry, preferring instead to show the excisions as silly.

The love story that evolves is the story of Sara, a college student, and Dara, a former student, who was jailed and kept in solitary confinement for two years for renting and selling banned videotapes of films by Alfred Hitchcock, Orson Welles, and Ingemar Bergman. Dara is now lucky to have found a job as a house painter. He has worshipped Sara from afar for a year, having seen her briefly at a student demonstration, and he leaves her coded messages hidden in library books. She never sees him, however, since men and women remain in separate sections of the library; he sees only her shoes from beneath the card catalog.

Gradually, the two young people begin to have “whispering computer chats,” and eventually meet secretly, including once in a cemetery and once in the emergency room of a hospital, avoiding situations in which anyone from the Ministry of Islamic Culture and Guidance will see them, since the meeting of a young man and woman who are not related is prohibited. Though they fall deeply in love, Sara is also being courted by Sinbad, a very wealthy older man, and her family knows that if she marries him, they will all be better off, financially.

Gradually, the two young people begin to have “whispering computer chats,” and eventually meet secretly, including once in a cemetery and once in the emergency room of a hospital, avoiding situations in which anyone from the Ministry of Islamic Culture and Guidance will see them, since the meeting of a young man and woman who are not related is prohibited. Though they fall deeply in love, Sara is also being courted by Sinbad, a very wealthy older man, and her family knows that if she marries him, they will all be better off, financially.

As the story progresses, Shariar Mandanipour comments about censorship in his own life. Though the Iranian Constitution allows free speech, it does not say that books and publications can “freely leave the print shop.” Hence, many books get printed and then never released, unable to get the required permit. Major film masterpieces are banned or censored, and headscarves unexpectedly appear in traditional stories for six-year-olds.

As the story progresses, Shariar Mandanipour comments about censorship in his own life. Though the Iranian Constitution allows free speech, it does not say that books and publications can “freely leave the print shop.” Hence, many books get printed and then never released, unable to get the required permit. Major film masterpieces are banned or censored, and headscarves unexpectedly appear in traditional stories for six-year-olds.

Throughout the novel, the author maintains an easy-going, conversational style and a self-deprecating, wry sense of humor. His characters become real people to him—and to the reader, who wonders constantly whether Sara and Dara will be able to escape the censor with their story, and when Dara is followed and is in danger of being assaulted by dark forces, the reader cares. Mandanipour has created a “novel” so rich with ideas, cultural history, and literary references–to writers such as Dostoevsky, Gogol, Kafka, and Malraux–that anyone interested in the creative process will be fascinated by his thinking as he creates a love story within the parameters of the present climate in Iran, which is, of course, the “real” story here. (High on my Favorites List for 2009.)

Notes: The author’s photo appears on http://www.sampsoniaway.org

The photo of Tehran appears on http://wikitravel.org

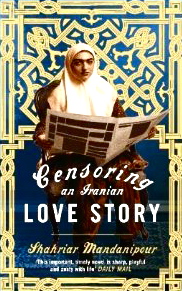

The cover of one paperback version of this novel is shown in the final image.