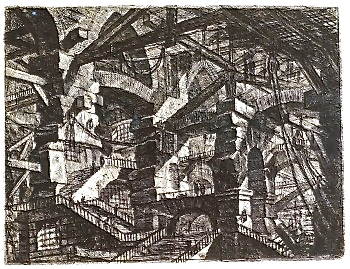

“Ever since I was a university student, I’ve loved the copperplate prints of the Italian artist, Giovanni Battista Piranesi. Piranesi left many sombre prints of prisons. He was a portrayer of imaginary prisons. Floor upon floor of high ceilings and dark metal staircases and also towers and aerial walkways. And of course metal drawbridges. His prints were full of those kinds of things. I wanted to build this house in that image. I even thought about calling it “Piranese Mansion.” – Kozaburo Hamamoto, owner/builder of the Crooked House.

From the opening lines of this locked-room mystery, author Soji Shimada piques the reader’s interest in the odd kinds of architecture which particularly lend themselves to mysterious events, describing, first, Cheval’s Palais Ideal (ca. 1916), a small rambling castle built by Ferdinand Cheval, a postman who picked up stones along his mail route to use in building his “palace.” Ludwig II’s Linderhof Palace (ca. 1886), with its cave and underground lake, oyster shell-shaped boat, blue lighting, and romantic paintings, might also have been ideal for such a mystery, as would some of the modern geometric design and architecture of Antonio Gaudi in the early twentieth century, he suggests. Ultimately, Shimada sets this newly translated 1982 mystery, the second novel of his career, at the top of Japan’s northernmost island, Hokkaido, facing the sea, in a fictional building designed by the main character, Kozaburo Hamamoto. From the outset, the author stresses that Hamamoto’s house is a very special creation, with floors that are not level and a tower with the same five degree tilt as the Tower of Pisa. Other irregularities with stairs, drawbridges, ladders, doors, and locks make the house seem more like the wild engravings of Giovanni Batista Piranesi than the “civilized” work of earlier architects, even those who stretched the concepts of home architecture in their own day.

From the opening lines of this locked-room mystery, author Soji Shimada piques the reader’s interest in the odd kinds of architecture which particularly lend themselves to mysterious events, describing, first, Cheval’s Palais Ideal (ca. 1916), a small rambling castle built by Ferdinand Cheval, a postman who picked up stones along his mail route to use in building his “palace.” Ludwig II’s Linderhof Palace (ca. 1886), with its cave and underground lake, oyster shell-shaped boat, blue lighting, and romantic paintings, might also have been ideal for such a mystery, as would some of the modern geometric design and architecture of Antonio Gaudi in the early twentieth century, he suggests. Ultimately, Shimada sets this newly translated 1982 mystery, the second novel of his career, at the top of Japan’s northernmost island, Hokkaido, facing the sea, in a fictional building designed by the main character, Kozaburo Hamamoto. From the outset, the author stresses that Hamamoto’s house is a very special creation, with floors that are not level and a tower with the same five degree tilt as the Tower of Pisa. Other irregularities with stairs, drawbridges, ladders, doors, and locks make the house seem more like the wild engravings of Giovanni Batista Piranesi than the “civilized” work of earlier architects, even those who stretched the concepts of home architecture in their own day.

This unique fictional residence is the setting for a celebration of Christmas, 1983, as owner Kozaburo Hamamoto, a widower, has invited eight guests to spend the holiday weekend with him at the Crooked House, also called the Ice Floe Mansion. The full-time residents of the house include Hamamoto, who, in addition to being the house owner is also the president of an industrial company; his daughter; a married couple who act as butler, chauffeur, and housekeeper; and a live-in chef, all of whom are happy to share the holidays with their guests. The guests who join the household for the weekend include a man who is president of a manufacturing company, his secretary/mistress, his chauffeur, an executive of his company, and three college students. Author Shimada, a perfectionist regarding details of all kinds, includes a Dramatis Personae, identifying all these characters, and a drawing of the house, officially the Ice Floe Mansion, showing its numbered rooms, the staircases, and the drawbridge to the tower. A special addendum also identifies the library, display room for art works, salon, sports equipment storeroom, table tennis room, kitchen and study.

This unique fictional residence is the setting for a celebration of Christmas, 1983, as owner Kozaburo Hamamoto, a widower, has invited eight guests to spend the holiday weekend with him at the Crooked House, also called the Ice Floe Mansion. The full-time residents of the house include Hamamoto, who, in addition to being the house owner is also the president of an industrial company; his daughter; a married couple who act as butler, chauffeur, and housekeeper; and a live-in chef, all of whom are happy to share the holidays with their guests. The guests who join the household for the weekend include a man who is president of a manufacturing company, his secretary/mistress, his chauffeur, an executive of his company, and three college students. Author Shimada, a perfectionist regarding details of all kinds, includes a Dramatis Personae, identifying all these characters, and a drawing of the house, officially the Ice Floe Mansion, showing its numbered rooms, the staircases, and the drawbridge to the tower. A special addendum also identifies the library, display room for art works, salon, sports equipment storeroom, table tennis room, kitchen and study.

A great admirer of the prison designs by Giovanni Batista Piranesi, Kozaburo Hamamoto, was attracted to the designs for staircases, drawbridges, ropes, and beams when he built his house. Click to enlarge.

Elements of mystery begin immediately, as one of the students, who had been helping to decorate the Christmas tree earlier, looks out the window into the garden and sees a thin stake sticking out of the snow. It had not been there earlier. He is even more surprised when he sees a second stake in the snow a bit later. He forgets about this as the host suggests they solve some mysteries which he will present to them as entertainment. No matter how difficult these puzzles may seem, one guest, a student, manages to solve all of them. Hamamoto, however, has one more mystery to challenge them, and they must all go to his tower to see it. Looking out the window, he points at the garden at the base of the tower and asks his guests to figure out the significance of the design of the flower bed below the tower, a garden which must be in that exact spot, with no leeway allowed in any direction. No one is successful in completing this task, but the guests are encouraged to keep working on it and, perhaps, return to the room another day to view the garden from above. That night, one of the women wakens to hear faint noises very close to her, then a metallic sound. Panicked, she screams, then sees a face with crazy eyes, charred skin on the cheeks, and a frostbitten nose staring at her through a gap in the curtains. Since her room is well above ground level and offers no foothold, she knows the face could not really have been looking inside, but she also knows that what she saw was not a dream – she had heard the creature roar.

Golem and his puppet from the 1915 silent film, The Golem and the Dancing Girl. The actor is on the right, the puppet on the left.

At breakfast time, one guest does not answer his door, and outside the room a dark figure is lying in the snow. As the guests go outside to get closer, they see that there are objects strewn around the figure. The “body,” however, turns out to be one of Hamamoto’s antique puppet dolls from Czechoslovakia – a Golem – with a missing head. When they return to the house, they find the body of a chauffeur who has come with one of the guests, stabbed to death with a hunting knife which has a white string attached. There are no footprints around, and no clues to how it happened or how it might be related to the earlier-discovered stakes, the golem, the noises heard by the woman that evening, or the golem’s missing head. When Hokkaido investigators arrive to do their jobs, they are as stymied by the murder – and several successive crimes, including another murder – as the guests, and they are just as unfamiliar with the bizarre architecture of this “mansion” as the guests have been. The arrival of Kiyoshi Mitarai with the constable of the local police station brings a whole new element into the story: Mitarai is a fortune teller, psychic, and self-styled detective, and he suddenly and dramatically becomes the new first person point of view for remainder of the novel.

Author Soji Shimada goes overboard here as he sets up seemingly unlimited barriers to the solving of crimes for which almost none of the guests have alibis. As the guests interact, some resentments, past histories, and jealousies are revealed, but these are buried so deeply in all the “atmosphere” of architecture and the excruciatingly detailed descriptions of the methods and materials of the murder that the characterizations feel incidental. When the final crime takes place, many readers will know who the murderer has to be, but the ways in which that person manages to outwit everyone else are so outlandish, unpredictable, and esoteric that I doubt that any reader will have any clue about how the murders actually took place before the Great Reveal at the end fills in the blanks. Sacrificing characterization for technique, Shimada makes this one of the most complex locked room mysteries ever, one to admire instead of love.

Photos. The author’s photo appears on https://archive.shine.cn

A great admirer of the prison designs by Giovanni Batista Piranesi, Kozaburo Hamamoto, was attracted to the designs for staircases, drawbridges, ropes, and beams when he built his house. This Piranese prison engraving is from 1761. https://commons.wikimedia.org/

This Golem and his puppet star in a Berlin silent film from 1915, The Golem and the Dancing Girl, starring Paul Wegener as the Golem. In this photo, the real Wegener is on the right, the puppet on the left. https://www.jmberlin.de/

Hamamoto’s collection of Tengu masks like this one have a role in the conclusion. https://www.kisspng.com/