“[Rilke says] that you have to love your solitude and hear the sweetness in the lamentation of the suffering that comes with it. Because you can’t take anyone there with you….It’s hard to be alone and hard to love and to really love is the hardest thing we have to do, and the most important thing.”

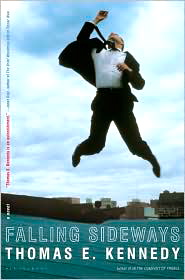

In the sec ond novel of the Copenhagen Quartet to be published in the US, American expatriate Thomas E. Kennedy shows his immense versatility, writing a totally different kind of novel from In The Company of Angels (2010), the first novel of the quartet. In The Company of Angels , which was my favorite novel of 2010, is a powerfully dramatic story of a man who suffered several years of torture under Gen. Augusto Pinochet in Chile before arriving, physically and emotionally ravaged, at a Copenhagen rehabilitation facility which treats victims of political torture. The ensuing novel is a study of man’s resilience and the resurgent power of love to heal the spirit. The novel is almost overwhelming in its tension and in its emotional drama as it deals with a variety of serious themes—love and death, freedom and confinement, and the worldly and the spiritual—as the characters live and recuperate from their traumas in Copenhagen.

ond novel of the Copenhagen Quartet to be published in the US, American expatriate Thomas E. Kennedy shows his immense versatility, writing a totally different kind of novel from In The Company of Angels (2010), the first novel of the quartet. In The Company of Angels , which was my favorite novel of 2010, is a powerfully dramatic story of a man who suffered several years of torture under Gen. Augusto Pinochet in Chile before arriving, physically and emotionally ravaged, at a Copenhagen rehabilitation facility which treats victims of political torture. The ensuing novel is a study of man’s resilience and the resurgent power of love to heal the spirit. The novel is almost overwhelming in its tension and in its emotional drama as it deals with a variety of serious themes—love and death, freedom and confinement, and the worldly and the spiritual—as the characters live and recuperate from their traumas in Copenhagen.

In this new novel, Kennedy depicts a different side of Copenhagen in a different style of writing, broadening his overall themes and his images of this city. Though no less serious in terms of its themes, Falling Sideways focuses on the business world of one company, a world writ small, instead of the world in its grandest terms, thematically. Though it is sometimes termed a satire, this novel is less a satire than it is a dark commentary on the shallow and self-absorbed lives of the employees  of “the Tank” as they navigate the shoals of big business during difficult economic times. Here Kennedy uses the business framework to establish a set of characters whose business lives become part and parcel of their personal lives, with the two different aspects of their lives so intertwined that the characters fail to grow or even recognize who they really are. They become, in essence, servants of their jobs and of the social milieu to which they have entrée as a result of their work. They no longer take the time to contemplate, appreciate or experience life’s mysteries, or feel love on anything other than the sexual level.

of “the Tank” as they navigate the shoals of big business during difficult economic times. Here Kennedy uses the business framework to establish a set of characters whose business lives become part and parcel of their personal lives, with the two different aspects of their lives so intertwined that the characters fail to grow or even recognize who they really are. They become, in essence, servants of their jobs and of the social milieu to which they have entrée as a result of their work. They no longer take the time to contemplate, appreciate or experience life’s mysteries, or feel love on anything other than the sexual level.

In fifty-three individual episodes, the most important main characters, who illustrate business stereotypes, gradually come to see the limitations of their lives, and some even prepare to make changes. Though these characters are quite different from the vibrant and emotionally moving characters of In the Company of Angels, they, too are ultimately dealing with the same themes of love and death, freedom and confinement, and the worldly and the spiritual, though for several of them the emphasis here is primarily on the worldly. Copenhagen itself becomes the equivalent of a character here, too, as it continues to reveal itself ever more fully as a vibrant force, for better or worse, in the personal lives of its residents.

Over the course of one week in autumn, three men from the Tank and their families reveal their dependence upon their business environment, showing in the process their own intellectual and spiritual limitations, and it is not until they are forced to confront issues of who they really are and where they are going that some of them begin to grow beyond their stereotypical behavior to become truly interesting individuals struggling with life’s realities. It is the autumn of their lives, physically, emotionally, and spiritually, and they have, as a group, squandered much of their earthly time chasing shadows.

Over the course of one week in autumn, three men from the Tank and their families reveal their dependence upon their business environment, showing in the process their own intellectual and spiritual limitations, and it is not until they are forced to confront issues of who they really are and where they are going that some of them begin to grow beyond their stereotypical behavior to become truly interesting individuals struggling with life’s realities. It is the autumn of their lives, physically, emotionally, and spiritually, and they have, as a group, squandered much of their earthly time chasing shadows.

Among the main characters, Frederick Breathwaite, an American in his fifties, has worked for the Tank for many years, the “public face” of the Tank. He has a devoted wife and a bright twenty-one-year-old son Jes, who has given up college to work for an Afghani refugee at a shop that makes keys and repairs shoes. Jes has more in common with the shop’s owner, he believes, than he has with other students or his family. Harald Jaeger, “a born bull- shitter,” has recently received a promotion to a high management position at the Tank. Divorced from an angry wife, he is a serial philanderer trying to find in sex what he is missing emotionally. Martin Kampman, the CEO of the Tank, is younger than all of these characters, a man hi red to “clean house” and reduce expenses by firing some long-time employees, which he promptly does. A man with no sensitivity and little conscience, he is the father of Adam Kampman, a seventeen-year-old who finds that he has more in common with the non-conforming Jes Breathwaite and his counterculture life than he has with his parents.

red to “clean house” and reduce expenses by firing some long-time employees, which he promptly does. A man with no sensitivity and little conscience, he is the father of Adam Kampman, a seventeen-year-old who finds that he has more in common with the non-conforming Jes Breathwaite and his counterculture life than he has with his parents.

As these characters from three families and different generations interact, they raise questions of honesty and ethics, the need for self-realization, the importance of the spiritual (through religion, philosophy, and literature), and most of all, the importance of true love. Filled with observations about particular places and institutions in Copenhagen, the novel is also laden with a huge variety of motifs and symbols, many of them associated with literature (including paraphrases from famous works, especially by Rilke), art (especially sculpture), jazz, the seasons, a ubiquitous sausage wagon (the oper ation of which Jes Breathwaite thinks would be a perfect job), and death (including the fear of two now-defunct nuclear power plants, fifteen miles from Copenhagen). The real names of the two boys, Adam and Isak, have biblical significance, and major themes flit in, out, and through of the lives of characters, who do not always recognize them or their importance. Kennedy has written an unusual book with multiple main characters, none of whom, at the beginning of the novel, are unique and living full lives. These characters illustrate through their reactions to the situations they face, however, many of the themes which Kennedy has also illustrated in In the Company of Angels, and as these themes unfold in Falling Sideways, some of the characters grow and escape their own limitations, becoming more human and giving the novel a surprising resonance. An unusual novel, told in an unusual way, to illustrate bigger ideas than first meet the eye.

ation of which Jes Breathwaite thinks would be a perfect job), and death (including the fear of two now-defunct nuclear power plants, fifteen miles from Copenhagen). The real names of the two boys, Adam and Isak, have biblical significance, and major themes flit in, out, and through of the lives of characters, who do not always recognize them or their importance. Kennedy has written an unusual book with multiple main characters, none of whom, at the beginning of the novel, are unique and living full lives. These characters illustrate through their reactions to the situations they face, however, many of the themes which Kennedy has also illustrated in In the Company of Angels, and as these themes unfold in Falling Sideways, some of the characters grow and escape their own limitations, becoming more human and giving the novel a surprising resonance. An unusual novel, told in an unusual way, to illustrate bigger ideas than first meet the eye.

ALSO by Thomas E. Kennedy: IN THE COMPANY OF ANGELS, KENNEDY IN COPENHAGEN, BENEATH THE NEON EGG

Photos, in order: The author’s photo is from his Facebook page.

A recurrent image: The sausage wagon, Grandpa’s Wieners, in front of the town hall, is from http://www.umamimart.com

The statue of a young man and woman in deep conversation, by Johannes Hansen (see p. 159) is one of many outstanding photos from Copenhagen which appear on http://copenhagendailyphoto.blogspot.com

The two Barseback nuclear power plants, on the tip of Sweden, only fifteen miles from Copenhagen, are no longer used, but there is no word yet on how they will be removed without damage to the environment. http://www.ydinenergianuoret.fi