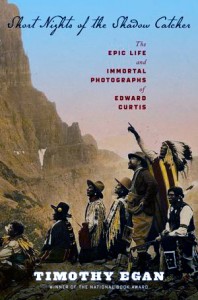

Note: This book was WINNER of the Carnegie Medal for Non-Fiction for 2013.

“We have wronged the Indian from the beginning. The white man’s sins against him did not cease with the explosion of the final cartridge in the wars which subjugated him in his own country. Our sins of peace…have been far greater than our sins of war…In peace, we changed the nature of our weapons, that was all; we stopped killing Indians in more or less a fair fight, debauching them, instead, thus slaughtering them by methods which gave them not the slightest chance of retaliation.” –Edward Curtis, 1912.

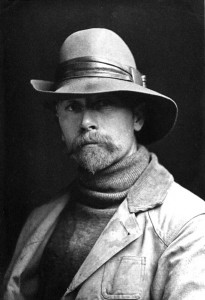

The scale, scope, and significance of this magnificent biography by National Book Award-winner Timothy Egan are only slightly eclipsed by the immense scale, scope, and significance of the work of his subject, photographer Edward Curtis (1868 – 1952). Curtis, at age twenty-eight, took his first photograph of a Native American when he did a portrait of “Princess Angeline,” an aged woman who was the last surviving child of Chief Seattle, for whom the American city was named. By 1896, when Curtis took this photo, it was illegal for Princess Angeline and other Native Americans to live within the city named for her father, and Curtis was all too aware of that sad reality. This woman was not only homeless in the traditional sense, she was bereft of the culture and belief system in which she had spent her entire life. By 1900, Native American tribes, nation-wide, had been devastated by disease and the superior weapons of the whites who wanted their land, and they now “owned” and occupied a mere two percent of the lands they had originally possessed. The small amount of land they had was in no way suited to their long cultural traditions, with the bison on which they depended for their food and skins all but wiped out and the land given to them completely unsuitable for their sustenance. Many starved to death on “their own” lands.

The scale, scope, and significance of this magnificent biography by National Book Award-winner Timothy Egan are only slightly eclipsed by the immense scale, scope, and significance of the work of his subject, photographer Edward Curtis (1868 – 1952). Curtis, at age twenty-eight, took his first photograph of a Native American when he did a portrait of “Princess Angeline,” an aged woman who was the last surviving child of Chief Seattle, for whom the American city was named. By 1896, when Curtis took this photo, it was illegal for Princess Angeline and other Native Americans to live within the city named for her father, and Curtis was all too aware of that sad reality. This woman was not only homeless in the traditional sense, she was bereft of the culture and belief system in which she had spent her entire life. By 1900, Native American tribes, nation-wide, had been devastated by disease and the superior weapons of the whites who wanted their land, and they now “owned” and occupied a mere two percent of the lands they had originally possessed. The small amount of land they had was in no way suited to their long cultural traditions, with the bison on which they depended for their food and skins all but wiped out and the land given to them completely unsuitable for their sustenance. Many starved to death on “their own” lands.

Though he was a family man with several young children, Edward Curtis spent the next thirty-three years investigating the remaining communities of Native Americans throughout the West, determined to record every aspect of their cultures before they vanished completely from history. Christian missionaries and the U.S. government had been determined to convert them and to eliminate their religions (which the missionaries did not consider to be religions at all), removing their children from their tribal settlements and sending them to schools away from their families and culture so they would become part of the American “civilization” totally alien to them.

Curtis was obsessed with the possibilities of using photography for saving these cultures for posterity – as a photographic record, at least. Ultimately, his self-imposed mission took him to virtually every remaining tribal area and state west of the Mississippi River, from New Mexico and Oklahoma to the Dakotas and Montana, back to Washington State, and eventually, north to Alaska. Spending weeks and often months with some tribal groups and visiting several others for a number of years in succession in order to be sure that he was recording their lives accurately, Curtis was totally devoted to his task, giving up virtually everything of personal value, working for no money at all (hoping that his commercial photo studio back in Seattle would support his family), and living most of his life hopelessly in debt in order to fulfill his personal mission.

Eventually, he would succeed in gaining the patronage of J. P. Morgan for a twenty-volume set of photographs with textual explanations, a monumental effort entitled The North American Indian. Again, Curtis worked without pay, and though he had foreseen a limited edition of one hundred copies of the twenty-volume set, each set selling for $5000 (the equivalent of about $125,000 then), that, too, was a financial disaster. Few people were interested, and even the Smithsonian would not purchase a copy. Despite the fact that Curtis took over 40,000 photographs using many new techniques, spent a great deal of time recording seventy-five Native American languages and vocabulary on wax cylinders, recorded songs from ceremonies and everyday life, described and photographed the costumes and appearances of dozens of tribes, and wrote entertainingly in all of his volumes, he always found himself alone and bankrupt. Importantly, however, his financial disasters never led him to compromise in any way. He refused to stint on his research into the waning cultures he was studying, remaining true to himself and true to them for his whole working life.

Though he would eventually rewrite the Battle of Little Bighorn, based on the interviews he conducted with the Native Americans whose first person observations of that battle differed markedly from the official version, he was prevented for many years from publicizing this research. With twelve more volumes left (of the twenty he would write) when he learned this information, he needed to cater to those who could help him – at least at first. Eventually, as additional financial support failed to appear, Curtis decided to simply tell the truth in his twenty volumes, and let the chips fall wherever they might.

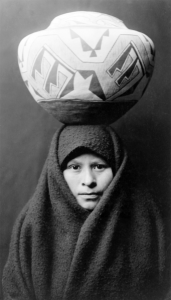

Author Timothy Egan is much like his subject in pursuing every possible detail, photograph, and incident related to Curtis, his life, and his commitment to tribal histories, even as it becomes all too obvious that Curtis’s mission is in a losing cause, both historically and personally. Capturing Curtis’s initial excitement as he begins his travels throughout the west in search of tribes still living according to their traditional histories, despite their straitened circumstances, Egan instills a similar excitement in his narrative beginning by including many reproductions of Curtis’s Native American photographs. Curtis’s disappointments in his inability to secure more financial support for this last chance to record the civilizations that are disappearing before his eyes are matched by the author’s almost palpable frustration with those in power who could have made a difference by helping to preserve even more information and even more cultural traditions.

As Egan presents his insights into Curtis’s personality, quirks, and even blind spots, this biography becomes a rarity – a biography closer to a classical Greek tragedy than to the more familiar saga of a man’s life.

Photos, in order: The author’s photo is from http://en.wikipedia.org

Princess Angeline’s photo is from: http://en.wikipedia.org

Hopi mother and child: http://en.wikipedia.org

Young Hopi woman: http://en.wikipedia.org

Zuni woman with pot: http://en.wikipedia.org

Nunivak mother and child: https://commons.wikimedia.org