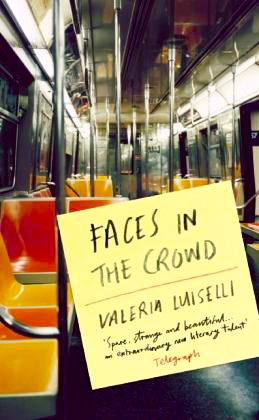

Note: This novel was WINNER of the Los Angeles Times Art Seidenbaum Award for First Fiction in 2015.

“I go back to writing the novel whenever I’m not busy with the children. I know I need to generate a structure full of holes so that I can always find a place for myself on the page, inhabit it; I have to remember never to put in more than is necessary, however, never overlay, never furnish or adorn. Open door, windows. Raise walls and demolish them.”

In this truly unique novel, so surprising and so exhilarating that I read it twice during the past week, I came to know, in a very real way, an author whose currently unwritten new novels I can hardly wait to discover in the future. Valeria Luiselli, a debut novelist from Mexico, left me stunned the first time I read this novel, though I was excited by her daring approach to writing and awe-struck at her ingenuous and totally honest inclusion of herself, for better and worse, in all phases of the narrative. By the time I had read it a second time, I was even more impressed by her ability to jump around and make herself at home within three different time periods while telling multiple, somewhat connected stories from four different points of view – that of her contemporary self, of her earlier self before her marriage, of her architect husband, and of Gilberto Owen, a virtually unknown Mexican author-poet from the late 1920s whose work the unnamed main character is trying to have published. None of these points of view are static, and the author sometimes merges characters and the details of their lives as she plays with reality and imagination, which she sees as both an outgrowth of reality and as an influence on reality. Fact and fiction become charmingly and often humorously combined in this novel about all aspects of the writing process as the author recreates herself both within her characters and within her own life. It is an amazing journey for the reader.

In this truly unique novel, so surprising and so exhilarating that I read it twice during the past week, I came to know, in a very real way, an author whose currently unwritten new novels I can hardly wait to discover in the future. Valeria Luiselli, a debut novelist from Mexico, left me stunned the first time I read this novel, though I was excited by her daring approach to writing and awe-struck at her ingenuous and totally honest inclusion of herself, for better and worse, in all phases of the narrative. By the time I had read it a second time, I was even more impressed by her ability to jump around and make herself at home within three different time periods while telling multiple, somewhat connected stories from four different points of view – that of her contemporary self, of her earlier self before her marriage, of her architect husband, and of Gilberto Owen, a virtually unknown Mexican author-poet from the late 1920s whose work the unnamed main character is trying to have published. None of these points of view are static, and the author sometimes merges characters and the details of their lives as she plays with reality and imagination, which she sees as both an outgrowth of reality and as an influence on reality. Fact and fiction become charmingly and often humorously combined in this novel about all aspects of the writing process as the author recreates herself both within her characters and within her own life. It is an amazing journey for the reader.

Direct narrative here is at a minimum, as the author creates brief paragraphs or episodes and moves around within them, providing information about herself and about the other characters who become narrators themselves. The novel opens in Mexico City with a precocious little boy awakening his mother with a question about mosquitoes. She goes on to tell the reader that she also has a baby daughter and an architect husband and that she does most of her writing at night, “A silent novel, so as not to wake the children.” Her worktable is covered with diapers, toy cars, Transformers, bibs, rattles and paraphernalia, but she works anyway. “Novels need a sustained breath,” she remarks, “That’s what novelists want. No one knows exactly what it means but they all say: a sustained breath. I have a baby and a boy. They don’t let me breathe. Everything I write is – has to be – in short bursts. I’m short of breath.” And she writes magnificently “in short bursts,” however short her breath may be.

Gradually, we come to know her earlier life in New York City when she is single and works as an editor whose job it is to find books by Latin American authors worth translating or reissuing. She leads a bohemian life surrounding herself with unusual characters, like Moby, who forges and then prints rare books on his homemade printing press, selling them to “well-to-do intellectuals”; Dakota, who sings in bars and subways and takes showers at the speaker’s apartment; and Pajarote, a philosophy student who sometimes stays overnight at her apartment. Her publisher, White, often shares stories about famous authors and is somewhat taken aback by the fact that the speaker is “the only Latin American woman [he knows] who wasn’t a friend of Bolano.”

Eventually, in the Columbia Library, the speaker finds a letter by Mexican poet Gilberto Owen in 1928 to fellow writer Xavier Villaurrutia, giving Owen’s address in Morningside Heights, New York, and she decides to find the building, eventually getting inside, then climbing to the roof, where she finds a dead tree in a bucket which she believes must have belonged to Owen, a motif that echoes throughout the novel.

Duke Ellington during the Harlem Renaissance in the late 1920s. The author imagines Owen seeing Duke Ellington perform there.

When she gets locked out and cannot get back down from the roof, she spends the night there, shivering, but makes the most of it: “I’d say that I began that night to live as if inhabited by another possible life that wasn’t mine, but one which, simply by the use of imagination, I could give myself up to completely. I started looking inward from the outside, from someplace to nowhere. And I still do, even when…the baby and the boy are asleep, and I could also be asleep.” She takes the dead tree home.

Ghosts and visions appear, whether they inhabit the house she occupies in Mexico City or in a New York bar where, perhaps drugged, she sees William Carlos Williams sitting beside her, the poet Zvorsky at a table, Ezra Pound hanging in a cage at the corner counter, and Garcia Lorca tossing him peanuts. She also sees Owen’s face in the crowded subway, even as he comments to someone else that he has also seen a girl in a red coat (the speaker) riding the subway, another repeating motif.

Finding literary works by Owen becomes problematic for her, however, so she eventually fabricates a manuscript and gets Moby to help her forge it, work supposedly translated by the famed translator Zvorsky. She imagines Owen seeing Duke Ellington in 1920s Harlem, and meeting with Garcia Lorca, a neighbor, and she feels no qualms about expanding on Owen’s life, remaining scrupulously honest as she imagines what his life might have been like, as he becomes friends with Ezra Pound and others. Before long, the imaginary life of Owen and the life of the author overlap and eventually coalesce. Owen, blind in later life, becomes friendly with Homer Collyer (his first name being symbolic), also blind, one of the famed Collyer brothers who became recluses and hoarders in the 1930s, filling their enormous house with “stuff,” including fourteen pianos, twenty-five thousand books, and tens of thousands of newspapers. The brothers’ deaths inside their jam-packed house in 1947 was one of New York’s biggest stories.

Owen often met with Homer Collyer sitting on these steps outside Collyer’s house, where they would both eat chocolate ice cream, supposedly made with cocaine. Twenty years later, as seen in this photo, when neighbors summoned the police, the house had been filled to the rafters with “stuff” by the two Collyer brothers, hoarders.

Gradually, details from Owen’s story and the author’s combine with details overlapping so that the reader is unsure what is fact and what is purely imaginative. But does it really matter, the author seems to ask? Most readers of this novel will thrill at the experience of participating in the creation of a novel on all levels, even when not all of the threads and details of the story leading to the conclusion are resolved. Though I am not a huge fan of a lot of post-modern writing, I loved this book for its insights into the writing process, its excitement, and for the obvious trust the author exhibits that her readers will understand and share her journey – and enjoy it as much as she herself has obviously done.

(Artfully translated by Christina MacSweeney, who maintains the author’s light attitude, even as the philosophical issues of reality and imagination unfold.)

ALSO by Luiselli: THE STORY OF MY TEETH and LOST CHILDREN ARCHIVE

Photos, in order: The author’s photo is from http://www.razon.com.mx

The building on Morningside Heights, where Owen supposedly had his apartment, is shown on http://www.propertyshark.com/

Duke Ellington as a young artist is seen here: http://elmiradornocturno.blogspot.com/

The photo of the young Ezra Pound, supposedly a friend of Gilberto Owen, may be found on http://www.poetryfoundation.org

Gilberto Owen often met Homer Collyer outside his house on 128th and Fifth Avenue, where they both enjoyed eating chocolate ice cream, supposedly flavored with cocaine. He never went inside the house, which, twenty years later, became famous when the two brothers, hoarders extraordinaire, died inside, under circumstances which the police and the public could not even begin to understand.http://www.nydailynews.com/

Many of the windows had been boarded shut to prevent neighborhood kids from breaking them and trying to get inside. The Collyers were reputed to be wealthy, and, in fact, were both millionaires, when adjusted for the current value of the dollar. Inside the house were fourteen pianos, over twenty-five thousand books, thirty-four bank account passbooks, and one hundred twenty tons of other debris collected by the brothers. http://www.nydailynews.com See also Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Collyer_brothers

ARC: Coffee House Press