Note: William McIlvanney was WINNER of the 1977 Crime Writers Macallan Silver Dagger Award for Laidlaw in 1977 and for The Papers of Tony Veitch (1983), and WINNER of the Scottish Arts Council Award for Fiction for Strange Loyalties in 1992.

My life was one terrible mess. Miguel de Unamuno had written something that applied to me, if I could think what it was. I read quite a lot of philosophy in a slightly frenetic way, like a man looking for the hacksaw that must be hidden somewhere, before the executioner comes. It was something about continuity. Unamuno says something like: if a man loses his sense of his own continuity, he’s had it. His bum’s out the window.”–Jack Laidlaw

Jack Laidlaw has never been one to hold back in his assessments, even in his assessments of himself and his problems, and in this third novel of William McIlvanney’s Laidlaw trilogy, published in 1991, after Laidlaw (1977) and The Papers of Tony Veitch (1983), main character Laidlaw faces himself, square-on. A detective with the Glasgow police, he is divorced, alienated from his teenage children, at a crisis in his relationship with a new woman, and addicted to the possibilities of escape through alcohol. When he learns that his troubled younger brother Scott, a teacher, has died in a pedestrian accident, his life “snuffed out on the random number plate of a car,” Laidlaw is about ready to “shut up shop on [his] beliefs and hand in [his] sense of morality at the desk. The world [is] a bingo stall.” Desperate to believe that Scott’s death must mean more than it seems to mean, Laidlaw also feels an inexplicable sense of guilt. Requesting a week’s time off from the job, he decides to investigate Scott’s death in an effort to learn how it happened and discover if it was truly random.

Jack Laidlaw has never been one to hold back in his assessments, even in his assessments of himself and his problems, and in this third novel of William McIlvanney’s Laidlaw trilogy, published in 1991, after Laidlaw (1977) and The Papers of Tony Veitch (1983), main character Laidlaw faces himself, square-on. A detective with the Glasgow police, he is divorced, alienated from his teenage children, at a crisis in his relationship with a new woman, and addicted to the possibilities of escape through alcohol. When he learns that his troubled younger brother Scott, a teacher, has died in a pedestrian accident, his life “snuffed out on the random number plate of a car,” Laidlaw is about ready to “shut up shop on [his] beliefs and hand in [his] sense of morality at the desk. The world [is] a bingo stall.” Desperate to believe that Scott’s death must mean more than it seems to mean, Laidlaw also feels an inexplicable sense of guilt. Requesting a week’s time off from the job, he decides to investigate Scott’s death in an effort to learn how it happened and discover if it was truly random.

Laidlaw, a thinker, philosopher, and reader, has always believed that the cases he investigates have their roots in institutional, fiscal, and political injustices, that they are more than “merely” legal offenses. “It was the crime beyond the crime that had always fascinated [him], the sanctified network of legally entrenched social injustice towards which [a] crime feebly gestured” on virtually every case he has worked on. Now, however, his “personal harpies” have come home to roost, “fouling [his] sense of his own worth,” and he is frantic, knowing he must resolve the issues of his brother’s death because it feels “unjust.” Unless he can come to terms with the randomness of this death and his own sense of guilt and responsibility, if any, he will remain unable to deal with issues involving his own life and his own mortality. “Where,” he wonders, “does an accident begin?” and “When did my brother’s life give up its purpose so that it could wander aimlessly for years till it walked into a car?”

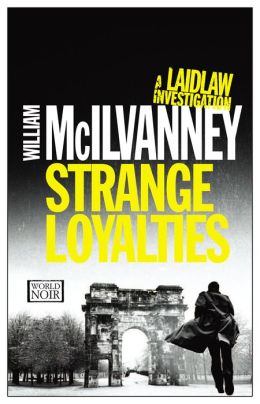

The Rotunda, the yuppie restaurant where Laidlaw and Brian Harkness meet to discuss the future before Laidlaw leaves for a week to investigate his brother’s death.

As he prepares to leave Glasgow for Ayrshire, where he grew up, to investigate Scott’s immediate past, Laidlaw’s young partner Brian Harkness meets him at the Rotunda Restaurant, in an ancient building recently restored, which has become a yuppie symbol of a regenerating city. There Harkness tells him about a new case that he and another “polis” officer, Bob Liffey, will be working on while Laidlaw is gone: a man’s body has been found just across the river from the Rotunda with a rope around its neck, one arm and all fingers broken. The contrast between the “people eating and drinking in the high brightness while in the darkness across the water where the light didn’t reach, a dead man lay abandoned,” is symbolic for the cynical Laidlaw: “Live high on the hog and don’t give a shit about other people.” It is in that mood that he departs, determined to get some answers.

A horse show at Floors Castle, near where Scott’s former in-laws live and where Laidlaw indicates that “I’m sure my ancestors went on foot and had to fight the ones that sat on horses. And maybe in my heart I’m still fighting them.”

What follows is a story that, in its depth, bears more thematic resemblance to Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment than it does to other noir novels. The main characters of both novels must to come to terms with the personal and ethical impact of their own behavior, and both engage in intense self-analysis and second-guessing from the outset. At the same time, however, Laidlaw also feels the obligations and sense of mission felt by Dostoevsky’s police investigator, Porfiry Petrovich, making Strange Loyalties doubly intense for the reader since Laidlaw must assume two responsibilities – what he owes to himself and what he believes he owes to the public. Though Strange Loyalties is obviously written for a different audience in a different period (and one would not want to push the analogy too far), McIlvanney shares with Dostoevsky the same intensity and seriousness of purpose in his analysis of the themes and of the guilt associated with death.

Edinburgh New Town, where Anna, Scott’s ex-wife, has moved: “This was in its origins the most English place in Scotland, built between 1765 and 1850. Photo by Dave Morris, Oxford, UK (See Credits below.)

McIlvanney differs dramatically from Dostoevsky (and from most modern noir writers, for that matter) in his dark humor, however. Without sacrificing his intellectual honesty and his well-earned literary credentials, McIlvanney writes from a breezy, irreverent, and often profane point of view, creating in Laidlaw a character whose flaws often get in the way of his personal success but whose sense of absurdity bubbles to the surface, no matter the circumstances. Laidlaw describes himself as a “strange searcher for justice – the polluted avenger, knight of the rusted sword.” Later, when he takes two pills for his hangover, he regards that as the equivalent of “sending in two rookie policemen to quell a riot.” He sees his father, a millworker, as “a cave with flowers round the entrance.” He tells one loathsome character that he resembles “a maintenance worker at Dachau or somewhere. You might convert the showers to gas..but you wouldn’t actually kill anybody.” As Laidlaw investigates the specifics of another death in his hometown in an effort to understand more about his brother’s death, however, he gradually broadens his conclusions about everyday life, often expressing these in wry aphorisms: “The rectitude of the aged is often just the fancy clothes in which incapacity likes to dress up” and later, continuing that analogy, “Fame’s just borrowed clothes.” His use of symbols deepens the characterizations and the themes. Scott’s paintings, for example, have a number of symbols, especially that of the “man in the green coat,” the mystery of whom Laidlaw discovers and explains, and he later relates the legend of the boy and the fox in Sparta as a sad allegory of his brother’s life.

Drumchapel with its broken windows and burned out apartments: It is here that Laidlaw meets TV commentator Michael Preston, who is interviewing a young couple, and from whom he hears “the banality of hopelessness.”

As Laidlaw gets to know Scott in relation to the four friends from the past who have played a huge role in his life, he comes to know and trust himself, however damaged by life he may be. In one moving, but surreal, scene, he gives a petty criminal a new chance as the man’s mother lies dying, showing his ability to mold his values to the circumstances and not see morality simply as a set of fixed rules. Despite the large number of characters and the complex interrelationships among them, the novel provides a perfect ending, tying up the details of the themes and the action at the same time that it suggests an appropriate coda: “And the meek shall inherit the earth, but not this week.” Memorable for its literary values, its creativity, and its intelligence, as much as for its themes and dramatic action, the Laidlaw trilogy has achieved the status of a classic during the author’s own lifetime.

NOTE: A new, paperback edition of this book will be released by Europa Editions in April, 2015.

ALSO by William McIlvanney: LAIDLAW and THE PAPERS OF TONY VEITCH

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on http://harrogateinternationalfestivals.com

The Rotunda Restaurant, an old Glasgow building, now a yuppie restaurant, represents the regeneration of the city of Glasgow. http://www.tripadvisor.co.uk/

Floors Castle horse show, near where Laidlaw’s former in-laws live: “They’re where it was, and I don’t like the way it was. It’s maybe a tribal memory. I’m sure my ancestors went on foot and had to fight the ones that sat on horses. And maybe in my heart I’m still fighting them.” http://www.horseandcountry.tv/news

Edinburgh New Town, “the most English place in Scotland,” built between 1765 and 1850, the place to which Scott’s wife Anna has moved. http://commons.wikimedia.org/ Photographer: [http://flickr.com/photos/davemorris/ Dave Morris] from Oxford, UK. Edinburgh, New Town, taken March 9, 2005 Original source: [http://flickr.com/photos/davemorris/61\

Drumchapel, with its broken windows and burned out apartments is where Laidlaw meets Michael Preston, a TV commentator who is interviewing an impoverished young man and his wife, and from whom he hears “the banality of hopelessness.” http://ukhousing.wikia.com/