“The age of glorious wars ended with the Meiji era…There isn’t much chance to die now on the battlefield. But now that old wars are finished, a new kind of war has just begun; this is the era for the war of emotion…And just as in the old wars, there will be casualties in the war of emotion, I think. It’s the fate of our age.”—Shigekuni Honda, Kiyoake’s best friend

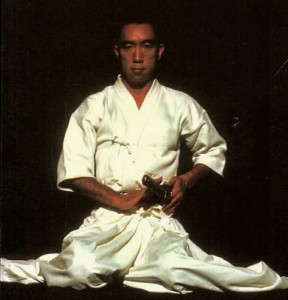

Just after au thor Yukio Mishima finished the final novel in his “Sea of Fertility” tetralogy on November 25, 1970, he disemboweled himself in a ritual suicide—seppuku—committed in the presence of four members of his private army. He was then beheaded, in accordance with ritual. Mishima, aged forty-five, believed whole-heartedly in the strengths of the old Japanese emperors and in the strong, aristocratic culture that had evolved from the samurai. He never forgave Emperor Hirohito for denying his godliness at the end of World War II, and he despaired of the political wrong-headedness he saw on both the right and the left a generation after the war. Spring Snow, written in 1966, is the first of the four novels of what is generally regarded as his masterpiece, a series which explores the essence of life, the spiritual beliefs which make that life meaningful, the obligations of man to a wider society, the relationship of chance to free will, and the glory of dying for one’s beliefs. By using a historical approach, with each of these novels taking place later than the previous one, and by repeating his characters, Mishima allows the reader to see Japanese cultural and social history change over a fifty-year period.

thor Yukio Mishima finished the final novel in his “Sea of Fertility” tetralogy on November 25, 1970, he disemboweled himself in a ritual suicide—seppuku—committed in the presence of four members of his private army. He was then beheaded, in accordance with ritual. Mishima, aged forty-five, believed whole-heartedly in the strengths of the old Japanese emperors and in the strong, aristocratic culture that had evolved from the samurai. He never forgave Emperor Hirohito for denying his godliness at the end of World War II, and he despaired of the political wrong-headedness he saw on both the right and the left a generation after the war. Spring Snow, written in 1966, is the first of the four novels of what is generally regarded as his masterpiece, a series which explores the essence of life, the spiritual beliefs which make that life meaningful, the obligations of man to a wider society, the relationship of chance to free will, and the glory of dying for one’s beliefs. By using a historical approach, with each of these novels taking place later than the previous one, and by repeating his characters, Mishima allows the reader to see Japanese cultural and social history change over a fifty-year period.

Spring Snow begins in 1912. The Meiji dynasty has ended, and Emperor Yoshihito has begun the Taisho dynasty. Kiyoake Matsugae is then a schoolboy at the exclusive, but rigidly spartan, Peers School, the former headmaster of which committed seppuko, establishing a much-admired legacy there. Kiyoake’s father, the wealthy son of a samurai family which was heroic during the Russo-Japanese War, wanted his son to be able to serve at the highest levels of the Imperial Court, and he gave away Kiyoake when he was a small child so he could be raised by the family of a court nobleman. Count Ayakura, his guardian, had royal connections but less wealth than Matsugae. By age fifteen, Kiyoake has learned court manners and traditions and associated with the children of the aristocracy, and appears to be ready to make his mark within the court. Kiyoake, however, hates the militant atmosphere of his school and prefers a more artistic, emotional life. He records his dreams on a regular basis and seems out of touch with absolute values.

The Great Buddha of Kamakura, seen by Kiyoake and his friends

Satoko Ayakura, two years older, is the daughter of Count Ayakura, and when Kiyoake begins to have romantic feelings for her, he is caught in the philosophical no-man’s-land between the harshly rigid values of his school (and much of his culture) and his own feelings of need for warmth and communication. Though she also seems to be attracted to him, he, a product of the cultural values of the time, refuses to admit that he needs anyone or anything to be a man, and he alternately encourages and rejects a relationship. When she, at age twenty (already “past her prime” for marriage), indicates her strong attraction to him, he withdraws, and any hope of a long-term relationship apparently vanishes.

The novel uses this relationship to illustrate Mishima’s themes of change. Though Satoko, as a woman, has virtually no importance at all in the overall scheme of things, the reader cannot help but identify with her and her love for Kiyoake. At eighteen, he is so conflicted and so much a product of his upbringing that many, if not most, contemporary western readers will despair of his ever achieving any enlightenment at all. The reactions of his friend Shigekuni Honda, a fellow-student, and of Iinuma, his personal tutor, both of whom are repeating characters in the tetralogy, keep the conflicts in focus and, through their different responses to the love story, guide the reader to an understanding of where the author is going with this novel as part of the tetralogy. Mishima’s several forays into philosophical analysis, in the course of the novel, provide wider perspective into his own attitudes toward life, love, and death.

The Shinbashi Railroad Station

Mishima, in the course of the novel, describes in great detail the houses, clothing, rituals, and even hairstyles of the period, and the density of the elaborate descriptions adds to the grand, epic sweep. The need for a character’s real feelings to be hidden, as the required patterns for communication are observed, is both frustrating and enlightening, and his use of symbols from nature—a dead dog at the top of a waterfall; a dead, blind mole; and Kiyoake’s fear of turtles—add to the atmosphere and the novel’s meanings. Some readers may not fully appreciate the sections of philosophizing, which do sometimes feel intrusive and not quite integrated, but these sections do counteract the unfolding romance and melodrama which might otherwise overwhelm the narrative. Despite Mishima’s world-wide reputation and the notoriety he achieved as a result of his bizarre ritual suicide, his writing is not esoteric. Instead, he writes in an accessible, descriptive style which graphically conveys the culture of Japan a generation before World War II.

ALSO by Mishima: THE FROLIC OF THE BEASTS, RUNAWAY HORSES (#2), THE TEMPLE OF DAWN (#3), STAR, LIFE FOR SALE

Photos, in order: The photo of the author is from http://faculty.washington.edu.

The Great Buddha of Kamakura, seen by Kiyoake and his friends during one summer vacation, is here: www.travel-destination-pictures.com.

The early twentieth century photo of Shimabashi Station (from which Satoko, her parents, and Kiyoake’s parents depart for Osaka) appears on http://en.wikipedia.org.