“It’s difficult to locate the Kusakado grave, hidden in a corner among many other intricate tombstones….Three small new gravestones stand huddled together in a shallow depression in the hillside. To the right is Ippei’s grave. To the left of that, Koji’s, and in the center lies Yuko’s. That Yuko’s grave appears charming and somewhat brilliant even in the twilight is because only hers is a living monument – a reserved burial plot – with her posthumous Buddhist name painted in bright vermilion.” – from the Prologue.

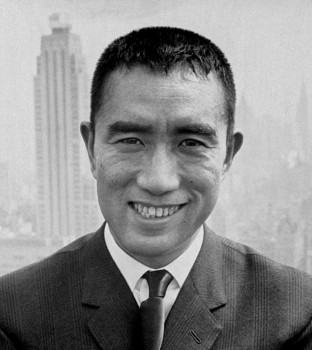

Among the most prolific novelists and playwrights in Japanese history, Yukio Mishima wrote thirty-four novels, fifty plays, twenty-five books of short stories, and many books of essays, before he committed ritual suicide after he failed in a coup attempt in Japan in 1970, when he was forty-five. This novel, written in 1961, now translated by Andrew Clare into English for the first time, is one of his early novels, quite different from his major work, the Sea of Fertility tetralogy, which traces Japanese history throughout the twentieth century. Here in a novel which has been described as a parallel to Japanese noh drama, with its wooden masks, Mishima writes an unusual psychological novel which begins with the ending, as the three main characters see themselves as “three fish caught up in a net…a net of sin.” As they pose for a picture in the small fishing port of Iro in West Izu, on a peninsula to the west of Tokyo, the reader has already become aware of “a final wretched incident,” the appearance of “droplets of blood [on the] dazzingly reflective surface of the concrete,” the “anguish” that Yuko, the main female character, feels within, and her comment about how “marvelous it would be to erect a tomb like this – the three of us lined up together.”

Among the most prolific novelists and playwrights in Japanese history, Yukio Mishima wrote thirty-four novels, fifty plays, twenty-five books of short stories, and many books of essays, before he committed ritual suicide after he failed in a coup attempt in Japan in 1970, when he was forty-five. This novel, written in 1961, now translated by Andrew Clare into English for the first time, is one of his early novels, quite different from his major work, the Sea of Fertility tetralogy, which traces Japanese history throughout the twentieth century. Here in a novel which has been described as a parallel to Japanese noh drama, with its wooden masks, Mishima writes an unusual psychological novel which begins with the ending, as the three main characters see themselves as “three fish caught up in a net…a net of sin.” As they pose for a picture in the small fishing port of Iro in West Izu, on a peninsula to the west of Tokyo, the reader has already become aware of “a final wretched incident,” the appearance of “droplets of blood [on the] dazzingly reflective surface of the concrete,” the “anguish” that Yuko, the main female character, feels within, and her comment about how “marvelous it would be to erect a tomb like this – the three of us lined up together.”

Chapter 1 begins as a flashback with Koji, a young, former college student and one of the main characters, appearing on the upper deck of a boat. Experiencing the morning sun and the “fragmented sunlight of his memories,” Koji recalls prison, constantly reminding himself that he has repented. “I am a different person now,” he asserts, before recalling “the day of the quarrel in the front garden of the hospital” which preceded a “night of bloodshed,” two years ago. Only one person is waiting for him when the boat arrives at the village where he lives – Yuko, with her blue parasol, who has decided to care for Koji, whom she sees as “a forlorn orphan.” Ironically, she is the wife of the third main character Ippei, the man Koji tried to kill and who now remains at home in need of full-time care. Surprisingly, Koji has agreed to live with them, helping Yuko keep the family greenhouse in operation. Yuko’s own role in the relationship among the three characters is central, of course, but her feelings are often inconsistent, perhaps a result of the “masks” she wears in her own relationships and the roles she plays as a wife. Ippei, now in his forties, had been a lecturer at a private university, where he was an expert in German literature, and he often hired his students, like Koji, to work in the western ceramics shop he inherited from his parents.

In an even earlier flashback, Koji, a “young, hot-headed youth,” first came to Ippei’s attention because of Koji’s tendency to fight, which Ippei regarded as “lighthearted… quarrelsome, and possibly extremely romantic.” Ippei advises Koji that “It’s a good thing to be able to fight and express your anger. The future of the world is all but in your hands. After that, ‘old age is all that awaits you.’ ” In an odd exchange, Ippei comments to Koji, who has not yet met Ippei’s wife Yuko, that she’s “a real odd case. I’ve yet to meet a stranger girl.” She is never jealous, despite Ippei’s many extramarital affairs, and she “doesn’t frighten at all,” yet she “loves Ippei terribly….It’s always the same gloomy, overly serious, stubborn frontal attack…it’s her army of love.” Concluding that Ippei is worthless and “insubstantial” for his beliefs, Koji falls hopelessly in love with Yuko before he has even met her, and “absorbed in his fantasy, he formed an exceedingly simple schematic picture in his mind.” First of all, the author says, “there was a miserable, despairing woman. Then there was a self-indulgent, heartless husband. And last, a hot -blooded, sympathetic young man. And with that the scenario was complete,” an over-simplification of the plot and motivations, to say the least.

Traditional cemetery. Yuko arranges for the three main characters to be buried in adjacent graves and purchases the space well ahead of her own death.

With a chronology which moves back and forth, before and after the critical fight and its aftermath, which sent Koji to prison for two years, the relationships among the main characters evolve even more fully, often revealed by what they say, more than by what they do. Bits of information are dropped into episodes without comment or explanation, increasing the suspense and the reader’s interests, at the risk of confusion. Ippei is sometimes cruel and even violent, and Koji, who has never had a real home, becomes frantically protective of Yuko and obsessively protective. She, in turn, tries to live up to her cultural and personal responsibilities and frustrates both Koji and Ippei with her behavior, which they often find unpredictable. The tension on all sides becomes palpable. The arrival of some new characters adds new elements to the relationships – love, hate, jealousy, resentment, obsession, and guilt – as viewpoints get expanded. As a typhoon approaches, a “slight rearrangement in the pattern of living” in the household takes place, and Koji falls into a state of despair with “hurricane-like speed,” as nature exerts its “pathetic fallacy.” In his final confrontation with he handicapped Ippei, Koji launches a verbal attack about Ippei’s possible motivations, and both reveal what they really want from life.

It is the Epilogue, in which author Yukio Mishima explains the origins of this story, which ultimately provides closure for the reader by referring back to the information previously revealed in the Prologue, expanding and explaining the characters, their “reality,” and the desire to be buried all together. According to Mishima’s translator, Andrew Clare, in his Translator’s Note, Mishima modeled this novel on the Noh play Motomezuka as a “parody.” The method by which the resolution is achieved here is clumsy and feels contrived, however, suggesting that the author was not sure how to resolve the action in a conclusion consistent with both noh drama and all the psychological detail he has created. By resorting to an almost journalistic explanation of facts and history to get him out of the difficulties he was facing creatively with the story, the author himself becomes the “deus ex machina” needed to tie up all the loose ends, an ending far different from the sure-handed conclusions within other novels by Mishima.

ALSO by Mishima: LIFE FOR SALE, RUNAWAY HORSES (#2, Sea of Fertility Tetralogy) SPRING SNOW (#1, Sea of Fertility Tetralogy) THE TEMPLE OF DAWN (#3, Sea of Fertility Tetralogy), STAR

Photos. The harbor at Iro, on a peninsula west of Tokyo, is where Koji lands following his stint in prison. https://www.booking.com

The author’s photo appears on https://www.gettyimages.com/

Traditional Japanese cemetery in the woods, where Yuko arranges for all three of the main characters to be buried together: https://www.alamy.com/

The Confederate Rose hibiscus features in the last pages of the novel: https://www.my-photo-gallery.com/

The Lighthouse at the harbor to Iro may be found on https://www.ibiblio.org