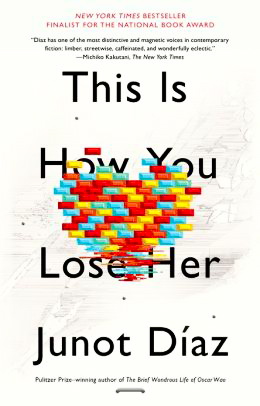

Note: This book was a FINALIST for the National Book Award, 2012, and was also a FINALIST for the Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence in Fiction.

“Here there are calamities without end – but sometimes I can clearly see us in the future, and it is good. We will live in his house and I will cook for him and when he leaves food out on the counter I will call him a zangano. I can see myself watching him shave every morning. And at other times I see us in that house and see how one bright day…he will wake up and decide it’s all wrong…I’m sorry he’ll say. I have to leave now.” – Yasmin, Ramon’s lover

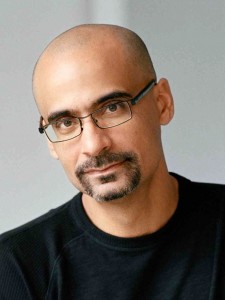

I wish I had read Th e Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao before reading this collection of stories. Junot Diaz’s first, and so far only, novel has won accolades from virtually everyone, winning the Pulitzer Prize, the National Book Critics Circle Award, the Los Angeles Book Prize, the Salon Book Award, the Center for Fiction’s First Novel Prize, and has even been shortlisted for the biggest prize of all – the IMPAC Dublin Award. I would have liked to see how Diaz melded all the disparate elements of a novel about the displacement of immigrants and the difficulties they have in creating new lives in a foreign country into such an intense and compelling novel, one which has astonished everyone I know who has read it. I had hoped that this collection of stories might provide me with the same kind of appreciation of Diaz’s work, so that I could then read the novel with new understanding.

e Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao before reading this collection of stories. Junot Diaz’s first, and so far only, novel has won accolades from virtually everyone, winning the Pulitzer Prize, the National Book Critics Circle Award, the Los Angeles Book Prize, the Salon Book Award, the Center for Fiction’s First Novel Prize, and has even been shortlisted for the biggest prize of all – the IMPAC Dublin Award. I would have liked to see how Diaz melded all the disparate elements of a novel about the displacement of immigrants and the difficulties they have in creating new lives in a foreign country into such an intense and compelling novel, one which has astonished everyone I know who has read it. I had hoped that this collection of stories might provide me with the same kind of appreciation of Diaz’s work, so that I could then read the novel with new understanding.

Consisting of nine short stories, all of which are about love, This is How You Lose Her describes whole worlds within the title itself. Four of the stories are named for the speaker’s lovers, and all of them reflect the speaker’s inability to experience love on a plane higher than that of the physical, which drives every aspect of his life. With a title that sounds a bit like an instructional manual by a now-frustrated macho man who is telling other similarly frustrated men how they can manipulate relationships in order to get and keep what they have – or at least not lose it – this collection of stories reveals the behaviors of several male speakers who have no clue about how to experience lasting love. Nor, it seems, do most of them even seem to want one single lasting love when two or more loves can provide at least twice as many thrills, twice as often.

With Yunior, who appeared in both Diaz’s first story collection, Drown, and in The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, as a main character in several of these stories, the narratives move back and forth in time, and for anyone who has read the biography of the author in Wikipedia or elsewhere, they become almost spooky in their closeness to the biography of the author himself. Many settings parallel those in which Diaz himself lived, beginning with his initial arrival from the Dominican Republic in the middle of winter, with his mother and brother, and their stay in New Jersey near an enormous city landfill, with a father/husband they had not seen in five years. Later references place him in Brooklyn, at Rutgers, and finally in Cambridge and Boston where he is working for his PhD and writing a book. The intense feelings aroused by these vividly described settings suggest that other aspects of Yunior’s life also parallel that of the author and his difficult life out of extreme poverty, which also includes an absence of guidance from a strong father figure who might have served as an example. As the speaker, be it Yunior (the author’s apparent alter-ego) or some other character, moves from one unsuccessful relationship to another in these stories, the reader cannot help but feel sorry for the degree to which hopes are dashed and women are used (willingly in most cases) and later hurt as a result of the male character’s insensitivity and, sadly, complete ignorance of the whole concept of respect. A belief in the importance of secrecy and the use of lies to achieve one’s own goals reflect a kind of arrogance and self-importance which allows the speaker to attract a woman initially but not share a real relationship with her, and then, almost tragically, not have any understanding of what he has done wrong.

Casa de Campo, the elite resort in the Dominican Republic to which Magda yearned to go when "bored" on vacation with Yunior.

As the stories progress, so, too, does the life of the main speaker, primarily Yunior, and while this is not a novel and does not have a “happily-ever-after” ending, the speaker at the end of the collection has learned a great deal and seems to have moved significantly beyond the difficulties he created for himself early on in some of the stories.

Throughout the collection, Diaz, through various speakers, reflects his fondness for Santo Domingo and his Dominican heritage, noting with affection his “blackness” in comparison to the lighter complexions of some of the women he meets, and even to Rafa, Yunior’s brother, whom he jokingly calls “white boy.” Even when these women are Spanish-speaking, some notation usually appears indicating what other country these woman may have come from, along with the differences in their cultures. Diaz himself, having progressed from poverty to a PhD, has been exposed to many different cultural groups and many kinds of slang along the way, from Spanish street slang, obscenities in multiple languages, and the offensive anatomical colloquialisms of “male-speak” frequently heard in hip-hop, hard rock, and the subway, in addition to the very different language of academia. All these “languages” combine here into an unusual “stew” which gives vibrancy and a sense of real life to the dialogue. None of these terms are translated for those who do not share the speaker’s background, however, and though they add color and atmosphere, and perhaps, even humor for those who do understand the jargon, they can be frustrating for those who cannot figure out specific meanings from the contexts in which these foreign words and phrases are used.

The Capotillo area of Santo Domingo, an area similar to where Elvis traveled with Yunior to meet Elvis's "baby-mama."

Ultimately, I came to appreciate the author’s style and the almost naïve intensity with which he recreates stories of love and loss and lessons learned (maybe) along with his hopes for the future. The changes of point of view from speaker to speaker, with the author occasionally interjecting himself into the story, do prevent a reader from identifying very closely with particular characters, though the fate of Rafa, for example, is sadly memorable, however briefly it may discussed be in one of the stories. Perhaps Diaz’s new novel, a science-fiction epic of the apocalypse, tentatively entitled Monstro (no release date yet), will turn me into the kind of rabid fan that most readers of The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao have become. I look forward to that.

Photos, in order: The author’s photo, supplied by Nina Subin of Penguin Group, appears on http://www.npr.org

The photo of the Casa de Campo resort is from http://www.kiwicollection.com

Capotillo in Santo Domingo, posted by Ventucles, appears on http://www.capotillomibarrio.org/