“When I read a book, I try my best, not always successfully, to let the wall crumble just a bit, the barricade that separates me from the book. I try to be involved.

I am Raskolnikov. I am K. I am Humbert and Lolita.

I am you…”–Aaliya Saleh

Told by Aaliya Saleh, a woman who “long ago abandoned [herself] to a blind lust for the written word,” this remarkable literary novel by Lebanese author Rabih Alameddine allows readers to follow the speaker into worlds which often feel familiar because of the emphasis on books the reader knows, but also into other worlds, previously unknown, based on her life in Beirut. The speaker tries to be empathetic – and totally involved – with her own reading, but she recognizes that most people read about crimes and tragedies believing they are done by “other people. ” We think we understand these “others” when authors show us (or tell us) during a novel that they have been “emotionally abused by their parents or had domineering fathers, or were dumped by their spouses.” When Aaliya says, “I am Raskolnikov…I am you,” she means it, but she also cautions the reader not to draw too many conclusions: “If you read these pages and think I’m the way I am because I lived through a civil war, you can’t feel my pain. If you believe you’re not like me because…only one woman chose to be my friend, then you are unable to empathize.” She is who she is, take it or leave it. “Like the bullet, I too stray,” she admits. “Forgive me.”

Told by Aaliya Saleh, a woman who “long ago abandoned [herself] to a blind lust for the written word,” this remarkable literary novel by Lebanese author Rabih Alameddine allows readers to follow the speaker into worlds which often feel familiar because of the emphasis on books the reader knows, but also into other worlds, previously unknown, based on her life in Beirut. The speaker tries to be empathetic – and totally involved – with her own reading, but she recognizes that most people read about crimes and tragedies believing they are done by “other people. ” We think we understand these “others” when authors show us (or tell us) during a novel that they have been “emotionally abused by their parents or had domineering fathers, or were dumped by their spouses.” When Aaliya says, “I am Raskolnikov…I am you,” she means it, but she also cautions the reader not to draw too many conclusions: “If you read these pages and think I’m the way I am because I lived through a civil war, you can’t feel my pain. If you believe you’re not like me because…only one woman chose to be my friend, then you are unable to empathize.” She is who she is, take it or leave it. “Like the bullet, I too stray,” she admits. “Forgive me.”

From the opening pages, Aaliya, in her seventies, is totally honest with the reader. She readily admits that she has misread the directions on some hair color and now has blue hair, something that does not really bother her because she owns only one small mirror. She goes on to explain that on January first, every year since she was twenty-two, she has begun translating a book from English or French into Arabic. This past year she translated W. G. Sebald’s Austerlitz, her second novel by Sebald, and she is undecided which novel to do this coming year. She has been toying with the idea of doing Roberto Bolano’s 2666, but as it is nine hundred pages long, she feels it will take two years. “I don’t hesitate when buying green bananas, but I’m slowing down,” she says. She has now completed thirty-seven separate translations of books she loves, both classics and modern, but these are personal to her, part of who she is, and she has never shared them with anyone else. Each translation is separately boxed, numbered, and stored out of the way in what might have been used once as the maid’s room in her apartment.

Within a few pages of the book’s opening, we learn that Aaliya is now a divorced, single woman whose father died when she was a baby and whose mother, by tradition, remarried her husband’s brother and produced five half-siblings for her. No one paid much attention to Aaliya at home, and she was “married off” at sixteen “to the first unsuitable suitor to appear at our door, a man small in stature and spirit.” The marriage lasted four years, and “nothing in our marriage became him like leaving it.” It was her job at a bookstore, after her divorce, that enabled her to read virtually anything she wanted – for fifty years. She had one best friend. These facts form the backbone for the “action” of this novel, which is closer to being a conversation with a book-loving reader than it is to a traditional novel.

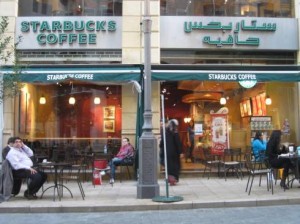

The Civil War in Lebanon, the Israeli siege of Beirut in 1982, and Black September are all mentioned but not explored in any detail as the novel moves back and forth through Aaliya’s memories and the books which have been part of her life. One memory of that war-filled period is of reading Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities by candlelight while Beirut burned. She knows there is an alternative to the kind of life she has lived in Beirut: “My books show me what it’s like to live in a reliable country [like England, France, or the US] where you flick on a switch and a bulb is guaranteed to shine and remain on, where you know that cars will stop at red lights…” She cannot help wondering, however, “if life [is] less thrilling if your neighbors are rational, if they don’t bomb your power stations…when things turn out as you expect more often than not…Does reliability reinforce your illusion of control?”

The restored Beirut Museum, which Aaliya loves to visit. Its collections were buried beneath it during the war to protect them.

Gradually, Aaliya fills in further details of her life, eventually bringing the chronology to the present, but it is a wayward journey, one the literature and music lover will thrill to take with her, reading slowly to savor her observations and the way she connects her life to observations by dozens of novelists and philosophers from all periods and from all over the world, often to the accompaniment of musical references to provide additional mood. Javier Marias, Antonio Munoz Molina, Joseph Conrad, Roberto Bolano, Nuruddhin Farah, and Michael Ondaatje appear in paragraphs with Mozart, Glenn Gould, Beethoven, Martha Argerich, and Olivier Messiaen. Vibrantly depicted scenes, stunning and earthy, include passages involving the “three witches” who live in her apartment building, her first passionate experience, her visit to a Palestinian enclave following a break-in at her apartment, her purchase of an AK-47, and a traumatic and unexpected visit from her mother. These scenes are interspersed throughout the more literary commentary, and it quickly becomes clear that plot in this character-based novel is its least important aspect, both to the author and to the reader (at least this one).

The tomb of a Roman noble, 2nd century A.D., showing the Legend of Achilles, Aaliya's favorite piece in the museum and one she studies often.

Aaliya and, one presumes, the author do not hold back in their opinions of contemporary publishing: “Most of the books published these days consist of a series of whines followed by an epiphany…the modern version of The Lives of the Saints…[but] less interesting because instead of rising into lush Heaven and His embrace all we get these days is a measly epiphany. I feel short-changed.” She feels sorry that James Joyce’s Dubliners is read now primarily because of “epiphany, epiphany, epiphany,” and she begs authors to “have pity on readers who reach the end of a real-life conflict in confusion and don’t experience a false sense of temporary enlightenment…You make me feel inadequate because my life isn’t as clear and concise as your stories.” Addressing the subject of writing programs, she notes, “You’re strangling the life out of literature, sentence by well-constructed sentence, book by bland book.” Despite its lack of strong plot, there is nothing bland about this fascinating and absorbing novel, and booklovers will smile at the ironies involved in its surprising conclusion.

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on the website of author Javier Marias: http://www.javiermarias.es

The Civil War in Lebanon, 1975 – 1990, is depicted here: http://www.lebmetal.com/

Aaliya says that she lives around the corner from Starbucks in Beirut. http://www.beirut.com/

The restored Beirut Museum is shown here: http://en.wikipedia.org/ Photo by Elie plus. The collections were buried beneath the structure to save them during the war.

Aaliya’s favorite piece in the Beirut Museum is Roman tomb with the Legend of Achilles around the base. 2nd century, from Tyre. http://en.beirutnationalmuseum.org/

ARC: Grove Press