“Strong nations will always take advantage of the weak if they can do so with impunity. This is a law of nature…They will see that their own interests are served. No doubt life would be better if both nations and people were guided by principle rather than by self-interest but…it is not the case. It is foolish to pretend otherwise.”

When the Jap anese invaded China in 1937 and French Indo-China in 1941, all part of Japan’s expansive efforts to establish the Greater East Asia Prosperity Sphere, the handwriting should have been on the wall for the colony of Singapore, one of Great Britain’s most important military and economic centers, located as it is between India and China. Hubris, and the sense that their military power could not be realistically challenged, however, led to Britain’s lack of military preparedness and the astonishingly quick takeover of Malaya and Singapore by the Japanese in 1942, handing the British what Winston Churchill called “the worst disaster and largest capitulation in British history.” Author J. G. Farrell recreates these traumatic days in Singapore as the final novel in his “Empire Trilogy,” which, like Troubles (1970), about the Easter Rebellion in Ireland (1916) and The Siege of Krishnapur (1973), about the Muslim Mutiny in India in 1857, combines Farrell’s cynicism, black humor, and sense of absurdity with his uncompromising honesty about colonialism–Britain’s greed, its colonial “mission,” its superior attitudes, and its cruelty toward the local people they consider their “subjects.”

anese invaded China in 1937 and French Indo-China in 1941, all part of Japan’s expansive efforts to establish the Greater East Asia Prosperity Sphere, the handwriting should have been on the wall for the colony of Singapore, one of Great Britain’s most important military and economic centers, located as it is between India and China. Hubris, and the sense that their military power could not be realistically challenged, however, led to Britain’s lack of military preparedness and the astonishingly quick takeover of Malaya and Singapore by the Japanese in 1942, handing the British what Winston Churchill called “the worst disaster and largest capitulation in British history.” Author J. G. Farrell recreates these traumatic days in Singapore as the final novel in his “Empire Trilogy,” which, like Troubles (1970), about the Easter Rebellion in Ireland (1916) and The Siege of Krishnapur (1973), about the Muslim Mutiny in India in 1857, combines Farrell’s cynicism, black humor, and sense of absurdity with his uncompromising honesty about colonialism–Britain’s greed, its colonial “mission,” its superior attitudes, and its cruelty toward the local people they consider their “subjects.”

The venerable Singapore merchant firm of Blackett and Webb and the family members who have run it at the expense of their workers come vibrantly alive here as they must deal with continuing strikes, labor unrest in rural areas, challenges to the government coming from the communists, and the influx of immigrants from other countries who raise the “threat” of a “melting pot” culture. The outbreak of war in Europe has made the demand for Blackett and Webb’s rubber supplies a high priority for Britain’s military cars and planes (not to mention commercial uses), and Blackett and Webb are poised to capitalize by manipulating prices, withholding product, attempting to form a monopoly, and evading the law as they cut down good trees in order to keep prices high, claiming the replanting costs against profits. The families’ personal fortunes and personal prestige more important to them than the future of the war effort, however patriotic they regard themselves. Associating with generals, the leaders of society, and local governors, the company’s representatives are busy planning their elaborate jubilee celebration. Even as the Japanese are attacking from the north, Walter Blackett continues with the jubilee parade preparations, while also trying to arrange the perfect commercial marriage for his daughter Joan.

On Feb. 15, 1942, Gen. Arthur Percival, carrying the British flag in the photo, surrenders to Japanese General Tomoyki Yamashita

Farrell has obviously spent a great deal of time researching not only the actions of the military and diplomatic corps from several countries, including the US and Australia, but also determining the personalities of the British characters (real) who act within the novel. Air Chief-Marshall Sir Robert Brooke-Popham (an old soldier remembering the good old days of World War I) and Lt. Gen. Arthur Percival (who seems unable to act during the emergency) have innumerable scenes which establish their attitudes and explain their actions–and inactions. In a surprise, Farrell also includes scenes in which the Japanese reveal their own points of view as officers Kikuchi, Matsushida, and his assistant Nakamura, prepare for the battle for Singapore.

Throughout the novel, Farrell handles innumerable plot lines (and battle lines) with assurance and historical accuracy, illustrating the reality of history within the context of the everyday lives of the not-very-sympathetic merchant princes of Singapore. Many of the younger characters, like young Matthew Webb, the heir to half the firm, are naive, and his previous background working for the Committee for International Understanding, a group associated with the League of Nations, has not prepared him for the cutthroat dealing of Blackett and Webb on the world stage. His attraction for a Eurasian woman is genuine, though his expectations are unrealistic. Walter Blacketts daughter Joan, on the other hand, trained by her father, is the consummate manipulator, a woman who will do anything to advance her own (and her family’s) greater wealth. Her brother Monty Blackett is a fool, so out of touch that in any other society he would be summarily dismissed as irrelevant.

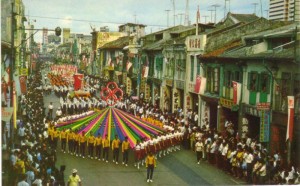

Singapore became independent on August 9, 1965. This is the 1968 National Day Parade.

As the Japanese come closer to attacking Singapore, the reader is stunned by some of the reactions of some members of the British community, concerned primarily that “the dignity of the British Government is at stake,” not with the real lives that are threatened. Just one month before the capitulation of the British to the Japanese, the Straits Times posts an advertisement from Robinson’s department store, giving instructions during alert periods: “We have roof spotters on duty…to give final ‘take cover’ alarm when danger is near. Until this warning is given we endeavour to continue normal business. Members of our staff carry on and give shoppers cheerful service. We have shelter facilities and seating accommodation in the basement.” As Singapore falls, the horrors are dramatic, revealing the inner resources–or lack thereof–of all the main characters, and as these escape–or fail to escape–Farrell has educated his readers so well that it is difficult to decide whether to be glad or sad about the fates of the characters we have followed for about five hundred pages. Ultimately, Farrell’s own opinions in favor of a world view shine through brightly. He was obviously farther ahead of his times than his main characters.

Notes: The photo of J. G. Farrell by Jane Brown appears on http://www.guardian.co.uk, when Farrell’s novel Troubles won the Lost Booker Prize in 2010.

On Feb. 15, 1942, Gen. Arthur Percival, carrying the British flag in the photo, surrenders to Japanese General Tomoyki Yamashita. http://www.cofepow.org.uk

Singapore became independent on August 9, 1965. The photo of the 1968 National Day Parade is from Wiki.

Also reviewed here: THE SIEGE OF KRISHNAPUR and TROUBLES