“I love the advice [about handling hawks] given by Nicholas Cox in his 1674 The Gentlemen’s Recreation: ‘You must by kindness make her gentle and familiar with you.’ I think it was this wisdom, passed down the centuries, which made hawks so appealing to me, this insight that an intransigent hawk, whose wildness is never lost and always resides just beneath the surface, can be reached, not by force, but by gentleness and kindness.”—Richard Hines, author

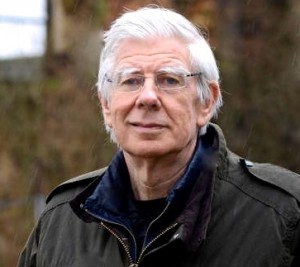

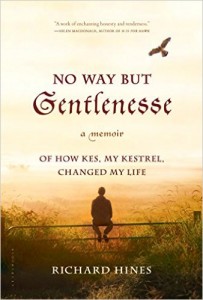

In this memoir of a man’s life, from his problematic childhood in the rural south Yorkshire mining village of Hoyland Common in the late 1950s, through his current, highly successful adulthood in Sheffield, also in South Yorkshire, author Richard Hines, like Nicholas Cox in the quotation (above), makes total connection with his reader in ‘gentle and familiar’ ways. Rarely, if ever, have I had such a feeling of intimacy with an author as he tells about his life and draws me in completely. The key to his whole life took place when he was just fifteen – the summer that he “manned” a kestrel, a small hawk. In a kind of reversal from what the reader might expect of someone who ultimately trained several more raptors, Hines conveys a feeling, not of his own power and strength, but of earnestness and real vulnerability. Here Hines trusts the reader and opens his heart, just as the kestrels he trained seem to trust and yield to him, as long as he “[kept] his side of the bargain to provide [them] with food and fly [them] free in the fields.” Ultimately, the author, having entertained and captivated the reader throughout the book, moves on in the conclusion, leaving in his wake many readers who have “lived” his life with him and found their own lives enlarged by their contact.

In this memoir of a man’s life, from his problematic childhood in the rural south Yorkshire mining village of Hoyland Common in the late 1950s, through his current, highly successful adulthood in Sheffield, also in South Yorkshire, author Richard Hines, like Nicholas Cox in the quotation (above), makes total connection with his reader in ‘gentle and familiar’ ways. Rarely, if ever, have I had such a feeling of intimacy with an author as he tells about his life and draws me in completely. The key to his whole life took place when he was just fifteen – the summer that he “manned” a kestrel, a small hawk. In a kind of reversal from what the reader might expect of someone who ultimately trained several more raptors, Hines conveys a feeling, not of his own power and strength, but of earnestness and real vulnerability. Here Hines trusts the reader and opens his heart, just as the kestrels he trained seem to trust and yield to him, as long as he “[kept] his side of the bargain to provide [them] with food and fly [them] free in the fields.” Ultimately, the author, having entertained and captivated the reader throughout the book, moves on in the conclusion, leaving in his wake many readers who have “lived” his life with him and found their own lives enlarged by their contact.

The first half of the book focuses on Hines’s childhood, beginning in 1955, when the author is eleven and living in Hoyland Common, a town in the shadow of the coal pits. His father and grandfather both worked in the mines, and as Hines reminisces about family life back then, we see a poor, working family dealing with a typically active young boy who is sometimes in trouble, but is mostly attentive to the “rules.” Close to his father, who is injured on the job more than once, Richard Hines also admires his brother Barry, six years older, an excellent student with whom he shares a bedroom. With his school friends Budgie and Towser, who reappear throughout the memoir, Richard slides down slag heaps, helps rescue and tame injured birds, and even encourages Towser when, one day, Towser brings a Luger under his jacket so he can shoot it into the slurry pond. Always a lover of birds and animals, the author keeps a magpie at home, a bird which, having never lost its wildness, terrorizes the neighborhood and inspires him, eventually, to release it into the wild. Not until he is on his way home from a hike to Tankersley Old Hall one afternoon does he see and get close to his first kestrel, a bird he decides that someday he will bring into his life.

Tankersley Old Hall, a ruined Elizabethan manor, where Richard Hines first gets close to a kestrel. Photo by A Burtz 910. See link in photo credits for more of his photos from South Yorkshire.

By the age of eleven, all the boys in his school take tests for advancement into a variety of new schools, these early tests perhaps reinforcing some of the class divisions within British society, he suggests. Though his family, his brother Barry, and Richard himself, had expected that he would go on to a more academic “grammar” school, he, unlike his brother, ended up at a Secondary Modern School – and not even in Section 1A, but in Section 1B. The author is thereby destined to deal with the horrors of the local school system with its iron-fisted corporal punishment and unsympathetic teachers. By 1960, when he is fifteen, however, he is reading books about falconry, including T. H. White’s The Goshawk, a passion which stimulates his decision that summer to try to “man” a hawk of his own. Acquiring a baby kestrel, he teaches himself how to work the hawk intuitively, deciding from the outset that he will never use jesses (cords around the hawk’s legs so that the hawk can be controlled by the trainer). He wants his hawk to be able to fly free even as they get to know each other.

Keeping his first kestrel in an old bunker from World War II on the property where his brother Barry has been living, the author is often watched by Barry who takes notes on the process. Barry eventually writes a popular book entitled A Kestrel for a Knave (1968), which goes on to become a huge success and eventually a prize-winning film in 1970. As a result, it is Barry Hines, the brother, who becomes forever associated with training the kestrel, not Richard, who is mentioned only in the dedication to Barry’s book. Richard does express some small annoyance in one interview, saying only that he was “anything but a knave,” as he is shown to be in Barry’s book, but he ignores any other slights he may have suffered.

David Bradley plays the part of Billy Casper, with a kestrel perched on his gloved arm, in the 1970 film of “Kes,” based on a Barry Hines’s “A Kestrel for a Knave.”

In the final section of the memoir, which contains less direct action than the first part of the memoir, the author puts his experience and learning into perspective – the idea of moving on, of rising above, of coming to terms. He goes on to attend Leicester Teachers Training College, studying Environmental Studies, and as he does his research for his dissertation, he makes a startling personal discovery. On a visit to the Falconry Centre in Gloucestershire, he recognizes Phillip Glasier, the man who founded the Centre, and when Richard asks him a question, Glasier answers “in a posh, loud voice, [which] intimidated me so much I could hardly take in what he was saying.” Richard Hines’s only contact with the upper classes had always been indirect – through the study of falconry – but he is struck, upon hearing this voice, by the gulf between the classes as revealed in the man’s accent and tone of voice. “For the first time I began to value my own heritage,” he says, and he eventually goes on to complete his degree and become a teacher, the head of a school, a film maker and writer for the BBC, and a lecturer at Sheffield Hallam University.

Jesses on a red-tailed hawk. The author refused to use these on Kes, allowing him to fly free, then return to his arm voluntarily. Photo by David Dunham.

In 2012, as he is entering his seventies, he returns once again to Tankersley Old Hall, where his first close sighting of a kestrel occurred, and it reminds him that “all of us have something of worth; a hidden potential, a talent or aptitude…[and that] this talent can inspire us to do things in life we might have thought impossible.” He, himself, has done this, and the example he sets with this memoir suggests that he, as a teacher and film maker, must also have inspired his students to believe in themselves. Vividly and honestly created, the book’s final lesson illustrates the four-hundred-year-old quotation which begins the memoir: “There is no way but gentlenesse to redeeme a Hawke,” a powerful metaphor for his own life.

Note: Two other books about “manning” hawks are reviewed on this site, the recent H is for Hawk by Helen MacDonald and The Pilgrim Hawk by Glenway Wescott, published in 1940. Neither of these books stresses the concept of “gentlenesse,” which so dominates Richard Hines’s book.

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on http://www.barnsley-chronicle.co.uk

Tankersley Hall, the ruins of an Elizabethan manor in South Yorkshire, is part of a collection of photos by A. Burtz 910 on Flicker: https://www.flickr.com

The kestrel is from an entry on https://en.wikipedia.org/

The photo from the 1970 film of “Kes,” written by Richard Hines’s brother Barry Hines, may be found here: http://filmsworthwatching.blogspot.com

David Dunham’s photo of jesses on a red-tailed hawk is posted on http://www.lotsofneatstuff.com