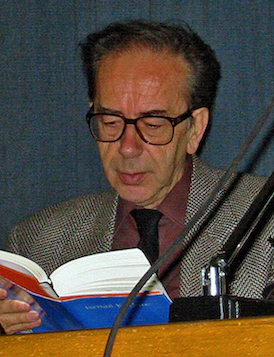

NOTE: Regarded as “one of the greatest European writers and intellectuals of the twentieth century,” Ismail Kadare was also WINNER of the inaugural Man Booker International Prize in 2005, WINNER of the Jerusalem Prize (2015), and WINNER of the Newstadt International Prize for Literature (2020).

“From an early age I felt that my mother was less like the mothers in [traditional] poems and more a kind of draft mother or an outline sketch which she could not step beyond. Even her white face had the frozen and inscrutable quality of a mask.….The maternal things mentioned in [traditional] poems and songs – milk, breasts, fragrance and warmth – were hard to relate to my own mother.”

In this  autobiographical novel of his early life and family in Gjirokastra, Albania, author Ismail Kadare focuses primarily on his mother, “the center of his universe” for his early years. Though she was not a warm, demonstrative person, her son stresses that she did have a caring nature and that it was “her self-restraint, her inability to cross a certain barrier,” that gave her a “doll-like mystery, but without the terror.” Her tears, he says, sometimes “flowed like those in cartoon films,” but when he asked her once about the reason for them, her answer “[made] my skin creep to recall it: ‘The house is eating me up!’ ” she claimed. Only seventeen at the time of her marriage to a man who was an only son, his mother was clearly lonely in the big old house to which she moved as a bride. The lack of other sons in her husband’s family eliminated the possibility of other young women eventually moving in and providing company for her. Her mother-in-law, famed for her “tight-lipped severity and for wisdom” also lived in the same house, and “an inescapable frostiness set in between the two,” almost from the beginning. Part of this coldness was connected to the traditions of the country regarding brides, their weddings, and the traditional roles of older women, but part, the author suggests, was almost certainly related to the nature of the house in which his mother found herself living after her wedding.

autobiographical novel of his early life and family in Gjirokastra, Albania, author Ismail Kadare focuses primarily on his mother, “the center of his universe” for his early years. Though she was not a warm, demonstrative person, her son stresses that she did have a caring nature and that it was “her self-restraint, her inability to cross a certain barrier,” that gave her a “doll-like mystery, but without the terror.” Her tears, he says, sometimes “flowed like those in cartoon films,” but when he asked her once about the reason for them, her answer “[made] my skin creep to recall it: ‘The house is eating me up!’ ” she claimed. Only seventeen at the time of her marriage to a man who was an only son, his mother was clearly lonely in the big old house to which she moved as a bride. The lack of other sons in her husband’s family eliminated the possibility of other young women eventually moving in and providing company for her. Her mother-in-law, famed for her “tight-lipped severity and for wisdom” also lived in the same house, and “an inescapable frostiness set in between the two,” almost from the beginning. Part of this coldness was connected to the traditions of the country regarding brides, their weddings, and the traditional roles of older women, but part, the author suggests, was almost certainly related to the nature of the house in which his mother found herself living after her wedding.

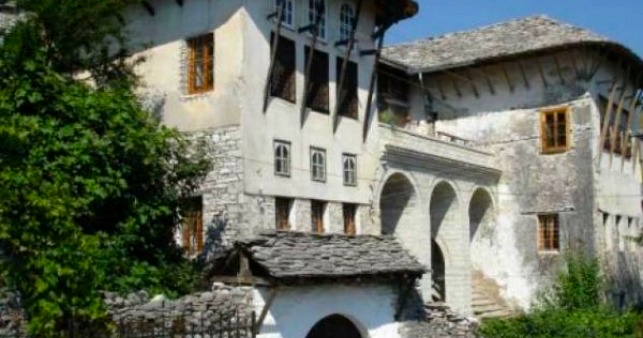

Totally different from the newer, warmer house in which his mother had lived with her own family before her marriage, the Kadare residence was a grim, three-hundred-year-old building almost devoid of people, and for Kadare, it is as much of a character here as the family itself. Its deep cellars, a cistern, fancy wooden stairs, uninhabited rooms, and secret subterranean passages, created an air of mystery, if not outright fear, for the new bride. Useless corridors and vestibules, rooms that they were not allowed to enter, and mysterious closets, added to the cold, impersonal atmosphere, and the house’s very real dungeon presented a constant threat, however oblique, to a bride accustomed to a house with “trees and birds, violins and Roma.” The marriage between his parents “was a mistake from the start…nobody ever understood the reason for [it].”

The style in which the author tells this story of his early life is different from what one may expect from reading his other novels. Here he affects an almost casual attitude as he shares his life and personal feelings, quite different from the the formal, often highly complex novels of ideas and poetry for which he has become famous. This more relaxed style and occasional humor bring him closer to the reader from the outset, making it possible to imagine a life in Albania quite different from what most readers have ever imagined, in a part of the world most of us have never seen. “Houses like ours seemed constructed with the specific purpose of preserving coldness and misunderstanding for as long as possible,” he says, as he documents the activities within the house with an almost offhanded attitude. And when he comments, soon after the narrative begins, that the frigidity and hostility between his mother and grandmother gradually increase over the years, it becomes completely believable when, a few pages later, he indicates that a very real and very secret legal trial began and continued for years between his mother and his grandmother, a trial overseen by his father.

Kadare himself, as he was growing up, expressed an early interest in writing, and when, at age twelve, he responded to an article in The Young Penman, he was mocked by his own uncles for his “touch of vanity,” that of inserting a middle initial in his signature A few years later, after his first book of poetry was published, he began to write novels, and he admits he became increasingly “big-headed,” during his studies in Tirana, and later Moscow. Time becomes compressed as his studies expose him to the work of the “Joyce-Kafka-Proust trio,” which is scorned in Moscow in favor of socialist realism, and though he and his friends were taught not to write like them,“we could hardly resist the temptation of writing precisely in their manner,” he comments. At home, he shares a “yellow bulletin” about banned books and about Freud with his father, and changes his father’s life, as a result. He continues to share stories of the family and the Doll, and he talks of the writers he admires, especially Shakespeare, and the classical stories which have influenced his ideas and his writing, especially that of Oedipus.

Albanian fustanella, the traditional costume, worn by singers who celebrated the visit of Ismail and Helena to the old house.

Back in Tirana with his bride Helena, also a writer, Kadare experiences success, while creating sometimes controversial pieces. In 1990, however, he is declared a traitor, and he and Helena flee to Europe, semipermanently. On a later return visit to Tirana to spend time with the Doll, she asks him a question he is never able to answer, a question he remembers again at her funeral ceremonies a few years later. Much later, he and his wife make what feels like a final trip to the ancient house in Gjirocastra, where he visits the house, surveys fire damage, and inspects some of the perennial repair work on it, reliving his earliest memories there as a child, while traditionally dressed singers serenade his wife and celebrate a newly found secret door. This is not a warm “return home,” and resolution, however. Despite the restoration work, Kadare finds the house and everything around it to be “grim, threatening,” not full of fond memories and love. For him, the resolution he hoped for turns out to be just “a continuation of the perplexity of long ago,” an echoing of life with the Doll.

ALSO by Kadare: THE ACCIDENT and THE FALL OF THE STONE CITY

Photos. The 300-year-old house where Kadare grew up appears on https://www.visit-gjirokastra.com

The author photo is from https://commons.wikimedia.org

The Gorky Institute of World Literature, where Kadare studied from 1958 – 1960. https://commons.wikimedia.org

Albanian fustanellas, who sang for Ismail and Helena on their visit to the old house. https://en.wikipedia.org

The damaged old house as it is being repaired after a fire: https://commons.wikimedia.org