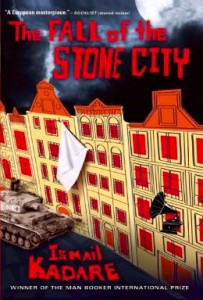

Note: Ismail Kadare became the first WINNER of the Man Booker International Prize in 2005 for his complete body of work.

“In [Gjirokaster] there were eleven former vezirs and pashas of the Ottoman Empire, four former overseers of the sultan’s harem, three former deputy managers of the Italian-Albanian banks, fifteen ex-prefects of various regimes, two professional stranglers of heirs apparent…not to mention three hundred former judges and more than six hundred cases of insanity: a lot for a medieval city now striving to become a communist one.”

Writing of Albanian life in Gjirokaster, the city of his birth, during World War II and its aftermath, Ismail Kadare creates a deceptive novel which looks, at first, as if it is going to be a simple morality tale. “Deceptive” is the operating word here, however. There is nothing simple about this novel at all, perhaps because Kadare, constantly under the gaze of Albania’s communist officials in his early years, always had to invent new ways to disguise what he really wanted to say without being censored. As a result, he began writing in a style akin to post-modernism, creating a literary soup which mixed fact and fiction, past and present, reality and dream, truth and myth, and life and death. By mixing up time periods, bringing ghosts to life, repeating symbols and images, and leaving open questions about the action of a novel, he was able to disguise the harsh truths of everyday life and the horrors of past history. That style continues in this novel from 2008 (newly translated by John Hodgson), despite the fact that Kadare was granted political asylum in France in 1990.

Writing of Albanian life in Gjirokaster, the city of his birth, during World War II and its aftermath, Ismail Kadare creates a deceptive novel which looks, at first, as if it is going to be a simple morality tale. “Deceptive” is the operating word here, however. There is nothing simple about this novel at all, perhaps because Kadare, constantly under the gaze of Albania’s communist officials in his early years, always had to invent new ways to disguise what he really wanted to say without being censored. As a result, he began writing in a style akin to post-modernism, creating a literary soup which mixed fact and fiction, past and present, reality and dream, truth and myth, and life and death. By mixing up time periods, bringing ghosts to life, repeating symbols and images, and leaving open questions about the action of a novel, he was able to disguise the harsh truths of everyday life and the horrors of past history. That style continues in this novel from 2008 (newly translated by John Hodgson), despite the fact that Kadare was granted political asylum in France in 1990.

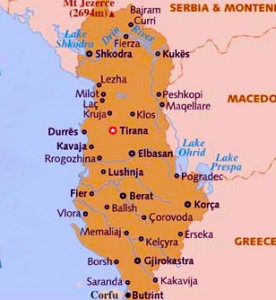

The novel starts simply enough. It is 1943. The Italians, who have ruled over Albania since 1939, have decided to retreat, ahead of the German invasion from Greece. Gjirokaster, at the southern tip of Albania, is one of the first cities the Germans come to in their attempt to “liberate” the country and restore their “independence.” Life in Gjirokaster is chaotic, at this point. The communists from “Red Russia” are making noises and recruiting support; hostile, nearby towns with ethnic Serbs are already under German control; people are fleeing into Gjirokaster from the mountains, and the nationalists want all foreigners out. As the German column enters the city, someone fires on the advance team. No one is hurt, but the Germans plan reprisals: “The [Byzantine age] city was to be blown up…Being blown into the air and made to leap and caper – all this was women’s stuff. In short, the stone city, so proud of its manly traditions, had been marked out to die like a woman.”

Soon after the Germans enter the city, however, the townspeople hear the music of Strauss, then Brahms, emanating from the gramophone at the home of Big Dr. Gurameto (not related to Little Dr. Gurameto, also a surgeon but of a different political persuasion). Colonel Fritz von Schwabe, commander of the German division and bearer of the Iron Cross, has called upon his “great friend, from university, my closest friend, more than a brother to me” – Big Dr. Gurameto. Soon word is leaked to the city that a hundred citizens held as hostages, including Jakoel the Jew, will be released. The city will not be bombed. The details of how all this came about will be the subject of gossip in the city for a decade.

Part II takes place in 1944, as the German Army retreats from both Greece and Albania, at the same time as the communists are arriving to take their place. Nationalists are arrested, as are some of the patients at the hospital, including some who have just had surgery. As one patient, arrested while under anesthesia, later observes, “All hell [has] been let loose in the city while [we were] absent…The times have moved on. Hours, days are passing and we are still stuck somewhere…Out of time. In reverse or minus time.” That image repeats years later, when word arrives that Stalin is going to visit the city: Time “was not just suspended, as it had been for the anaesthetized hospital patients nine years before; it was going backwards at great speed,” making the narrative of the two Drs. Gurameto even more complex to follow. The dinner between Big Dr. Gurameto and Col. von Schwabe is, once again, the subject of an investigation.

Castle at Gjirokaster, begun in the 12th century, and containing the Cave of Sanisha

This image of patients anesthetized and in surgery becomes a repeating symbol. Big Dr. Gurameto often has dreams in which he is a surgical patient being operated on by himself, and Col. von Schwabe comments on the fact that the doctor once operated on him: “You brought me back to life, but to your own misfortune.” Surgeries, of course, leave scars, which also reappear in the imagery. Old stories, like folk tales, reoccur: In one, a young boy is sent out to invite a stranger to a dinner, gets frightened of the idea of ghosts as he passes a graveyard, throws the invitation into the graveyard and runs off. Later a dead man shows up at the dinner. In another motif, the ghost of Sanisha, the sister of the violent eighteenth century Ottoman ruler Ali Pasha Tepelene, appears more than once as a woman with a pale face and long dress. Part III features the story of the Cave of Sanisha, “universally imagined as the deepest and most terrifying dungeon of the city’s prison, which was housed in the ancient castle [of] Gjirokaster.”

Byzantine arches at the Castle, photo by Bruce Macphail

Other readers may be as baffled as I often was, as they try to figure out what Kadare wants us to take at face value, what may be symbolic or mythical, and what events are “real” in one place but mythical in another. The many chronological shifts, details taken out of time, and characters who might be real, or ghosts, or walking dead left me unsure where the author was going and why. The tone of the novel is not consistent, putting an additional burden on the reader: Part One, dealing with the dinner of Dr. Gurameto and Col. von Schwabe, feels like a morality tale. The author’s style is quick and to the point, but keeps the reader at a distance, as an observer, rather than as a participant in the narrative. Part II, which takes place a year later, begins as a history lecture about Albania’s many political changes, before it shifts to an almost farcical style about the communists, and then leads to the gruesome interrogations and tortures which dominate Part III.

The author himself seems to have recognized the problem of coherence, since he inserts himself into the narrative in the concluding pages. “Here is what happened,” he states, before going back to 1953 and bringing events, and some surprises, up to the present. His explanation of what happened feels “real,” but even that explanation still contains Kadare’s trademark combination of fact and fiction, reality and dream, truth and myth, leaving me, at least, with questions about what “really” happened here. Perhaps that was the author’s point.

The Stone City and surroundings

ALSO by Kadare: THE ACCIDENT and THE DOLL: A PORTRAIT OF MY MOTHER

Photos, in order: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/

The map of Albania is from:http://www.lonelyplanet.com Gjirokaster is at the southern tip of the country. View is from the Castle.

The Castle of Gjirocaster, which also includes the Cave of Sanisha, built by Ali Pasha Tepelene, is also from http://www.jitourism.com/

The photo of the arches at the Castle and additional information from photographer Bruce Macphail may be found on http://www.balkantravellers.com

The panorama of Gjirokaster appears on http://en.wikipedia.org/

ARC: Grove Press