“Adolph Hitler, a supposed teetotaler…didn’t care about wine as a drink, [but] he did recognize its potential to confer social status. In May of 1945, when allied forces liberated the Eagle’s Nest, Hitler’s mountaintop redoubt in the Bavarian Alps, they found half a million bottles of wine, including Lafite, Mouton-Rothschild, and Yquem.”

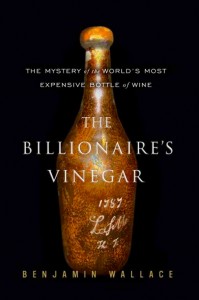

Could the bottle of Lafite, with the initials of Thomas Jefferson and dated 1787, then sitting on a pedestal at Christie’s auction house, possibly have been part of a newly discovered Nazi hoard? On December 5, 1987, Michael Broadbent, the head of the wine department of Christie’s, readied himself to auction off this bottle, the oldest authenticated bottle of red wine ever to come up for auction at Christie’s. He knew its provenance was crucial, as it would certainly become the most expensive bottle of wine ever sold. Some suggested that it had a Nazi history. Others knew that a section of the Old Marais district in Paris had recently been torn down, and wondered if the bottle could have been found walled up in some basement to avoid theft during various wars. Then again, Thomas Jefferson had sent hundreds of cases of wine home to Monticello (and some to George Washington) when he left his job as Minister to France to become the Secretary of State, and one of these cases may have been lost or stolen. Auction excitement was high, and speculation was rife because of the age and importance of this bottle, not just for its qualities as wine but also because it was an important historical artifact.

Could the bottle of Lafite, with the initials of Thomas Jefferson and dated 1787, then sitting on a pedestal at Christie’s auction house, possibly have been part of a newly discovered Nazi hoard? On December 5, 1987, Michael Broadbent, the head of the wine department of Christie’s, readied himself to auction off this bottle, the oldest authenticated bottle of red wine ever to come up for auction at Christie’s. He knew its provenance was crucial, as it would certainly become the most expensive bottle of wine ever sold. Some suggested that it had a Nazi history. Others knew that a section of the Old Marais district in Paris had recently been torn down, and wondered if the bottle could have been found walled up in some basement to avoid theft during various wars. Then again, Thomas Jefferson had sent hundreds of cases of wine home to Monticello (and some to George Washington) when he left his job as Minister to France to become the Secretary of State, and one of these cases may have been lost or stolen. Auction excitement was high, and speculation was rife because of the age and importance of this bottle, not just for its qualities as wine but also because it was an important historical artifact.

Author Benjamin Wallace

The bottle had been consigned to Christie’s by Hardy Rodenstock, a German wine collector and former pop-band manager, who refused to say exactly where it had come from, revealing only that in 1985 he had received a phone call about a hidden cellar in some unidentified 18th century house in Paris which was being torn down. It supposedly contained about a hundred bottles, two dozen of which were engraved with the initials “Th.J.” All the bottles, he said, were from 1784 – 1787.

Rodenstock was well known in the wine market. He often wrote long articles for wine magazines, he was a regular buyer at wine auctions at Christie’s and Sotheby’s in London, and he had accumulated a circle of buyers around him who trusted his judgment. Beginning in 1980, he had hosted elaborate wine-tastings to which only the most elite were invited, and he offered tastes of the very rarest wines, including at one point, one of the Yquems from the Jefferson discovery.

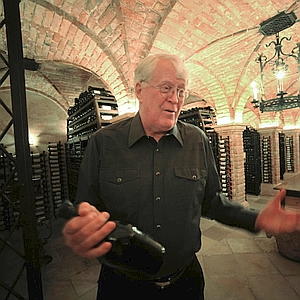

Michael Broadbent, head of Christie’s wine department in 1987

By the time the auction of the first bottle of Jefferson wine was held at Christie’s in London in December, 1987, sophisticated wine lovers on both sides of the Atlantic were aware of this discovery and were, for the most part, enthusiastic. After a bidding war between Marvin Shanken, a former investment banker and owner of the Wine Spectator, and Kip Forbes, son of publisher Malcolm Forbes, who was determined to obtain this bottle to display in New York at the inauguration of the Forbes Galleries, Forbes was the winner at $156,000. The press and the wine world went crazy, leading Malcolm Forbes to grumble on a TV program the next day that “The Forbes family would be far better off if Mr. Jefferson had just drunk the damn thing.”

Wine auction. The bottle in the photo resembles that of the Jefferson wine.

Though there had been no history of fraud within the highest echelons of the wine business, to that point, questions began to arise about this bottle after the sale. Many felt that “It [was] odd that whoever first found the [dozens of] bottles would not have shopped them to the highest bidder, instead of automatically selling to Rodenstock.” Some began to investigate. Lucia Goodwin from the Monticello Library, who had spent years organizing Jefferson’s extensive financial records of his life in France, including all of his purchases, could neither prove nor disprove the attribution of this wine to Jefferson. There was no evidence at all that he had ever purchased a 1787 Lafite. In fact, Jefferson, “a hero of meticulousness,” had recorded a purchase of only two of the four wines that Rodenstock had found. From 1787 on, Jefferson had also ordered all his wines directly from the chateaux involved. Any initials on the bottles would have had to have been put on them after the sale by one of Jefferson’s own people. The Rodenstock bottles were all engraved with Jefferson’s initials, but there was no record at Monticello of the significant expense that that process would have involved for the many bottles Jefferson purchased. Even more strange, Jefferson had never been known to use this style of engraving on any of his other bottles, though all of the Rodenstock bottles used this engraving style.

Kip Forbes and Family Friend

As several more of the Jefferson bottles came up for auction over the next few years, each one setting a new record, questions continued to arise regarding the bottles’ provenance. Privately, Rodenstock sold four more bottles to William Koch, who bought bottles dating from 1737 and 1771, far earlier than the Jefferson bottles.

International wine experts, especially some of those who had gone to Rodenstock’s tastings and come back with questions about the age of a few of the wines being served there, became increasingly suspicious. The big problem regarding the Jefferson wines, however, was proving that the wine in the bottles was not as advertised: If a bottle was opened and found to be adulterated, the evidence was destroyed! And if the wine proved to be “right,” the opened bottle would have been wasted as an investment.

Hardy Rodenstock, consigner of Jefferson wines

Eventually, questions arose about the glass bottles themselves, the ullage (the amount of evaporation as seen in the level of the wine between the cork and the “shoulders” of the bottle), and ultimately, even the instruments used to engrave the bottles. Strangely, at subsequent tastings, Rodenstock’s men quickly recovered the corks and sealing wax after the bottles were opened, so no one had access to them for testing purposes.

In the second half of the book, author Benjamin Wallace takes the reader from 1987, when the first sale took place, to the present, detailing the new techniques which can now be used (and were used on the Jefferson bottles) to date bottles, wine, sediments, engraving, wax, and corks. High tech labs, with experts on everything from tests for germanium, thermoluminescence, carbon, and lead, create a fascinating story of how the wine market has evolved to the present and the safeguards now in place to prevent mistakes regarding the age of wines. Benjamin Wallace keeps the excitement high as he details the search for information about the Jefferson wines and the eventual outcome. (The lengthy lawsuits which resulted from these sales have now been settled. See links at end of the photo credits.)

William Koch, photo by Mark Randall

Photos, in order: The author’s photo is from http://www.npr.org

Michael Broadbent’s photo, by Kent Hanson, may be found here: http://www.winespectator.com

The wine auction photo is from http://images.businessweek.com

Kip Forbes with the family friend appears here: http://www.forbes.com

Hardy Rodenstock’s photo may be found on http://weindeuter.blogspot.com

William Koch’s photo is from

http://www.thedrinksbusiness.com

Regarding subsequent lawsuits: The result of Michael Broadbent’s lawsuit against RandomHouse for publishing this book may be seen here: http://www.winespectator.com

The story of the lengthy Koch v. Christie’s lawsuit is here: http://www.huffingtonpost.com