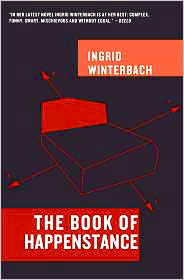

Note: Ingrid Winterbach is widely regarded as one of South Africa’s most important writers. She was WINNER of three major awards, including the W. A. Hofmeyr Prize, for Best Afrikaans Literature, for this novel in 2007.

“I have not led an admirable life. I have been irresponsible and inconsiderate in most of my relationships. But concerning my [shell collection], I am and have been all reverent and devout attention. It is my way of acknowledging the wonders of creation…one of the very few things I do to tend my spiritual well-being.”

In this challengi ng and important philosophical novel, South African author Ingrid Winterbach explores the particulars of one woman’s life to provide insight into the universal, as, of course, do many other good authors, but she goes way beyond the one or two significant new insights one has grown to expect. Here, her main character, Helena Verbloem, a writer and lexicographer of the Afrikaans language, wants to understand nothing less than the very essence of life itself, what it means to be alive (if life can be said to have “meaning” at all, rather than simply existing as a fact), and how the Big Bang began a chain of events which has led ultimately to sentient human beings, often imperfect, such as Helena herself. She wants to know how man developed a consciousness and a conscience, and how – and even if – individuals, such as herself, have any unique place in the grand scheme of life. Why am I here, she wonders, and does my life matter?

ng and important philosophical novel, South African author Ingrid Winterbach explores the particulars of one woman’s life to provide insight into the universal, as, of course, do many other good authors, but she goes way beyond the one or two significant new insights one has grown to expect. Here, her main character, Helena Verbloem, a writer and lexicographer of the Afrikaans language, wants to understand nothing less than the very essence of life itself, what it means to be alive (if life can be said to have “meaning” at all, rather than simply existing as a fact), and how the Big Bang began a chain of events which has led ultimately to sentient human beings, often imperfect, such as Helena herself. She wants to know how man developed a consciousness and a conscience, and how – and even if – individuals, such as herself, have any unique place in the grand scheme of life. Why am I here, she wonders, and does my life matter?

Helena’s life has been messy. A divorced mother in her late forties, she rarely sees her daughter, who is now an adult living on her own. Her extended family has died, some of them having disappeared during the years when others depended on them most. She has had a series of love affairs, seeking, unsuccessfully, some connection and understanding with people she has met. Her novel has not been a great success. When offered the chance to move to Durban to work on a project to collect and preserve those words in the Afrikaans language which have fallen into disuse, she packs up her belongings and thirty-seven of her favorite shells and moves to Durban. Sharing an office with her boss at the Museum of Natural History, she spends her lunch hours with paleontologists and other researchers in the cafeteria, fascinated by their discoveries and the ancient collections they tend. She learns, among other things, details of how life itself began in the sea countless millions of years ago, then emerged from the primal ooze onto land, differentiating into new species, some of which survived and some of which did not.

When her flat is broken into, three months after her arrival, and her shells stolen, she is devastated.

“All my things I view as earthly goods, all of them replaceable—but not the shells. The shells are heavenly messengers! The shells I have been collecting for a lifetime. They are my most prized possessions. Over the years I have taken (with a few notable exceptions) more pleasure in these shells than in people.”

The remainder of the novel consists of Helena’s search to discover what happened to her missing shells, her futile attempts to gain information about the theft, her work on the “dead” words she is recording, and her continuing study of the earliest life forms and their parallels with the present. During her lunch hours with the paleontologists, she finds out more about the sea, about how the beautiful variety of shells takes place, and about the animals which once lived inside the shells. The shell of a nautilus, she is surprised to learn, is the result of a “logarithmic spiral, a clean predictable, mathematical process, rhythmic and balanced.” And she thinks about the fact that these animals had to die in order for her to possess their shells. The more she learns from her researcher friends, the more she begins to believe in “happenstance,” those accidents which occur to species which lead, over time, to the mutations which allow them to adapt more successfully to changing conditions, even as their predecessors die out.

The remainder of the novel consists of Helena’s search to discover what happened to her missing shells, her futile attempts to gain information about the theft, her work on the “dead” words she is recording, and her continuing study of the earliest life forms and their parallels with the present. During her lunch hours with the paleontologists, she finds out more about the sea, about how the beautiful variety of shells takes place, and about the animals which once lived inside the shells. The shell of a nautilus, she is surprised to learn, is the result of a “logarithmic spiral, a clean predictable, mathematical process, rhythmic and balanced.” And she thinks about the fact that these animals had to die in order for her to possess their shells. The more she learns from her researcher friends, the more she begins to believe in “happenstance,” those accidents which occur to species which lead, over time, to the mutations which allow them to adapt more successfully to changing conditions, even as their predecessors die out.

In structuring her novel, the author is clearly aligned with James Joyce, whose work on Ulysses she refers to several times in the novel. Like him, she believes that the novel is a container, and that if an author can include within that novel/container, every possible detail about one person at one time in his/her life, that the novel comes closest to recreating life itself. In this case, Winterbach thinks monumentally, putting Helena Verbloem’s life into the context of the whole evolutionary cycle as Helena tries to understand herself, her life, and her love of her collection of shells. The resulting novel is astonishing—so grand in concept, so challenging, as the author leads the reader step-by-step through many discussions of the evolutionary cycle, and so exhilarating in its bold creativity, that I found myself constantly amazed at the unique ways in which the author employs all this information to create a whole new understanding of Helena, even as Helena herself is evolving with new understandings of her world.

In structuring her novel, the author is clearly aligned with James Joyce, whose work on Ulysses she refers to several times in the novel. Like him, she believes that the novel is a container, and that if an author can include within that novel/container, every possible detail about one person at one time in his/her life, that the novel comes closest to recreating life itself. In this case, Winterbach thinks monumentally, putting Helena Verbloem’s life into the context of the whole evolutionary cycle as Helena tries to understand herself, her life, and her love of her collection of shells. The resulting novel is astonishing—so grand in concept, so challenging, as the author leads the reader step-by-step through many discussions of the evolutionary cycle, and so exhilarating in its bold creativity, that I found myself constantly amazed at the unique ways in which the author employs all this information to create a whole new understanding of Helena, even as Helena herself is evolving with new understandings of her world.

Winterbach, unlike Joyce, employs a simple, uncomplicated writing style to examine her many themes and subjects, always relating even the biggest themes–life, love, and death–to Helena and the people around her. And as Helena comes to believe that chance, happenstance, and coincidence are the single guiding principle in life, she discovers that others at the museum are more open to other interpretations. Her friend Sof, the daughter of a pastor, believes “that the shell, and not the human being is the crowning glory of creation. Or one of its crowns. Or one of the pearls in its crown. Perhaps you should think..that your lost shells are now in heaven, adorning the throne of God.”

Just before the dramatic conclusion, Sof asks Helena, “What do you think, should a novel come to a final conclusion? Should it pitch towards a resolution?…Does life move toward resolution? Is anything ever concluded?” As Helena thinks about what life will be like a hundred million years from now, and then two hundred million years from now, with, perhaps, deadly killer worms and highly evolved ants, she gains new insights about her role in the world, but she has no way of preparing herself for a sudden, momentous event which intrudes into her own life. Her perspective may, of course, change with the unexpected. Then again, maybe it won’t.

ALSO by Winterbach: TO HELL WITH CRONJE and THE ELUSIVE MOTH

Photos, in order: The author’s photo is from www.litnet.co.za.

The nautilus shell, cut in the center to show its compartments, is from http://naplesseashellcompany.com

In 2009, paleontologists from the University of Chicago, funded by National Geographic, discovered a nine-foot long fossil of “the missing link” between fish and animals who live on land. The fossil was found in the Arctic Circle. This animal had legs and the ability to breathe air, an astounding bridge between the lungfish, which can breathe but not support itself on fins, and the Coelecanth, which has strong fins but cannot breathe air. http://therockyriver.com

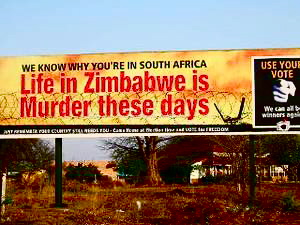

Constable Modisane, who had been investigating the theft of Helena’s shells, is abruptly transferred to Musina (Messina), a “frontier town” on the border with Zimbabwe. Thousands of starving Zimbabweans have fled the violence in that country, illegally entering South Africa by climbing under fences and stretching South Africa’s resources to the breaking point. Here a billboard urges illegals to return home to vote against Robert Mugabe. Does democracy, as a type of government, nullify the idea of survival of the fittest? http://digitaljournal.com

The last photo is of a small fish from Malaysia which may be similar to the much larger fossil discovered in the Arctic. It can live on land and can breathe air. Photographed by Colin Jong: http://colinjong.com