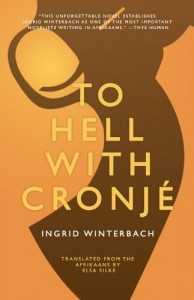

Note: Newly translated into English, this Afrikaans novel was WINNER of the 2004 Hertzog Prize in South Africa.

“In this wide expanse [of plain] it is easier to see the larger pattern—to correlate the sills from a distance, as they run from one rocky hill to another…with the shales forming the darker layers between. Marshy in the prehistoric past with an abundance of plant and animal life. Ferny plants and mammal-like reptiles. Now it is barren and dry. Wide and desolate. Instead of giant reptiles, lizards scurry about, the warm-blooded meerkat…darts across the veld.”

An unusu ally strong war novel which ranks with the very best, To Hell with Cronje by Ingrid Winterbach shows characters whose lives have been permanently changed by the Second Boer War (1899 – 1902), and raises the question of whether any of them—men, women, and children–will ever be able return to a peaceful life after the brutality which has created a new “normal” within their nation. How, she asks, can one cope with the horrors of war on any level? What resources can men develop that might allow them to survive personally? Boer men in their forties and fifties have been drafted, forced to leave their farms and their families to fight on horseback, often in other parts of the country, protecting “their” land against the British (the “Khakis”). Wives and children are left behind to defend their rural farms by themselves, and even if they survive both the climate and bloody attacks from the enemy, they are often taken to concentration camps while their property is looted and burned. Most do not survive the incarceration.

ally strong war novel which ranks with the very best, To Hell with Cronje by Ingrid Winterbach shows characters whose lives have been permanently changed by the Second Boer War (1899 – 1902), and raises the question of whether any of them—men, women, and children–will ever be able return to a peaceful life after the brutality which has created a new “normal” within their nation. How, she asks, can one cope with the horrors of war on any level? What resources can men develop that might allow them to survive personally? Boer men in their forties and fifties have been drafted, forced to leave their farms and their families to fight on horseback, often in other parts of the country, protecting “their” land against the British (the “Khakis”). Wives and children are left behind to defend their rural farms by themselves, and even if they survive both the climate and bloody attacks from the enemy, they are often taken to concentration camps while their property is looted and burned. Most do not survive the incarceration.

Four Boer soldiers who have served in a variety of fortified camps (laagers), with an assortment of career officers–mostly incompetent, in their opinion–have set out on a mission to return young Abraham Fourche to his mother in Ladybrand. Not quite twenty, Abraham has witnessed the horrifying death of his brother, who died in his arms during the devastating Battle of Droogleegte, and he is now shell-shocked, mute, and unresponsive. Those traveling with him are Willem Boshoff, a fifty-year-old who serves as Willem’s caretaker, and two men in their forties—Reitz Steyn, a geologist during peace-time, and Ben Maritz, a naturalist who collects insects and plants and teaches natural history at a Capetown college. They carry with them a letter from their general, Servaas Senekal, to Gen. Bergh, who is in hiding near the Orange River. They also have a map, acquired through some tribesmen they meet on the trip. For six brutally hot days, during which time they allow themselves only a mouthful of water a day, they head north into unknown territory, gradually detaching themselves emotionally from where they have come from. “They have left everything behind. They no longer have any discernible roots.”

Their meeting with Gert Smal, a white man, and Ezekiel, a Kaffir who is an expert on history and the Bible, leads them into another camp, thought to be a “transit camp” for soldiers who are unfit for battle. General Bergh, the commanding officer, is away when they arrive, and they are suspected of being traitors and deserters. The camp is a symbolic Purgatory, with all the maimed and psychologically unfit soldiers waiting, waiting, waiting, mending clothing and repairing saddles until General Bergh returns. All complain about the way the war is going and about the bad decisions of the generals, and all try to deal with the war and their inner conflicts as best they can, some through drink, some through reading, some through reliving memories both good and bad, some through dreams, and some through prayer. Reitz and Ben Maritz keep hold of their sanity by collecting insects and samples of rock and recording their findings in a journal for posterity. Reitz, not religious, seeks help, at one point, from an old healer who lives in the hills behind the camp, while Ben, also a scientist, dreams of a messenger, a woman wearing a feathered hat.

For the first half of the book, the author establishes her complex characters, building the reader’s identification with them and establishing her themes instead of creating action scenes of warfare. When General Bergh returns and asks Reitz and Ben to make a fireside presentation of their research to the camp, the novel grows more complex. Their talks provide clear explanations of the process of evolution and the importance of fossils, and many fundamentally religious soldiers suddenly hate Reitz and Ben for undermining their faith–for some, the only comfort they have in war. When General Bergh decides to send Reitz, Ben, and Gert Smal on a mission to decoy the British and create a diversion, the action is furious, and the results from that point until the conclusion are powerful, involving, and thematically intense as hell breaks out with little possibility of a heaven.

Though Winterbach can be lyrical in describing the countryside, her sentences are usually short and clear, and the action is mostly internal, rather than external. Her treatment of themes is just as clear. Her description of the process of evolution, as revealed in the landscapes through which her characters travel, for example, is also seen in the evolution of her characters’ own thinking. The scientist Reitz, who becomes the main character in the latter part of the novel, goes through a period in which he seeks answers in religion, evolving into a man who considers all possibilities. All the characters, however shy they may be to “talk” about it, begin to wonder about love and its power–religious love, sexual love, love of country, love of fellow man, love of family—and ultimately to question the power of man ever to know answers on a grand scale. Perhaps, as one character suggests, there are no answers. Perhaps our objective should be “to take from life whatever little we can get. It all goes so swiftly.” Powerful, dramatic, and filled with characters one cannot help but like, the novel gains impact in its presentation of big themes which expand beyond its South African setting. To Hell with Cronje is one of my Favorite Novels of this year.

Though Winterbach can be lyrical in describing the countryside, her sentences are usually short and clear, and the action is mostly internal, rather than external. Her treatment of themes is just as clear. Her description of the process of evolution, as revealed in the landscapes through which her characters travel, for example, is also seen in the evolution of her characters’ own thinking. The scientist Reitz, who becomes the main character in the latter part of the novel, goes through a period in which he seeks answers in religion, evolving into a man who considers all possibilities. All the characters, however shy they may be to “talk” about it, begin to wonder about love and its power–religious love, sexual love, love of country, love of fellow man, love of family—and ultimately to question the power of man ever to know answers on a grand scale. Perhaps, as one character suggests, there are no answers. Perhaps our objective should be “to take from life whatever little we can get. It all goes so swiftly.” Powerful, dramatic, and filled with characters one cannot help but like, the novel gains impact in its presentation of big themes which expand beyond its South African setting. To Hell with Cronje is one of my Favorite Novels of this year.

Also by Winterbach: THE BOOK OF HAPPENSTANCE and THE ELUSIVE MOTH

Photos, in order: The author’s photo is from www.humanrousseau.com

The earlier surrender of General Cronje to the British at Paardeburg in February 1900, is shown in this painting by George Scott: http://www.military-art.com This site specializes in military art prints from ancient history through the war in Afghanistan, all of which are available for sale.

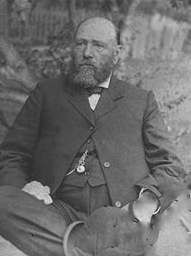

General Piet Cronje, while a prisoner at St. Helena, is shown on http://en.wikipedia.org

One of YouTube’s most remarkable videos is of a 111 year-old survivor of the Boer War. This includes some old films of the war.