“Write only the truth. Tell them about the flares you see at night, and the oil on the water. And the soldiers forcing us to escalate the violence every day. Tell them how we are hounded daily in our own land. Where do they want us to go, tell me, where? Tell them we are going nowhere. This land belongs to us. That is the truth.”—The Professor, a militant rebel leader, to Rufus.

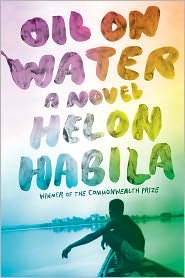

In his third novel, award-winning Nigerian author Helon Habila continues the dialogue he began with Waiting for an Angel, a novel set in the 1990s during the government of Sani Abacha, who colluded with Big Oil in the Niger Delta and is accused of having taken an estimated $3 billion – $4 billion out of the country. A tyrant who used his military for his own ends, Abacha allowed no hint of dissent, and journalists were routinely jailed and held without trial, as was the main character of Waiting for an Angel. As a result of these abuses, Nigeria was expelled from the Commonwealth of Nations, and most of the free world enacted sanctions against it.

In his third novel, award-winning Nigerian author Helon Habila continues the dialogue he began with Waiting for an Angel, a novel set in the 1990s during the government of Sani Abacha, who colluded with Big Oil in the Niger Delta and is accused of having taken an estimated $3 billion – $4 billion out of the country. A tyrant who used his military for his own ends, Abacha allowed no hint of dissent, and journalists were routinely jailed and held without trial, as was the main character of Waiting for an Angel. As a result of these abuses, Nigeria was expelled from the Commonwealth of Nations, and most of the free world enacted sanctions against it.

When Oil on Water opens, ten years have passed. Sani Abacha died in 1998, and international sanctions have been lifted, but Nigeria’s elected government officials and the military are still colluding with the oil companies, and all are still getting rich. The poor are still poor–unable to fish in their rivers for food, unable to grow crops on their oil-soaked land, and unable to breathe the air without choking. In oppositio n to the military and the politicians, a significant rebel movement has now arisen, determined to obtain oil money on their own, and they will do virtually anything to get it. Constantly fighting the military, the rebels have brought a new kind of danger to the countryside, and the poor villagers never know who will invade their villages and threaten them next.

n to the military and the politicians, a significant rebel movement has now arisen, determined to obtain oil money on their own, and they will do virtually anything to get it. Constantly fighting the military, the rebels have brought a new kind of danger to the countryside, and the poor villagers never know who will invade their villages and threaten them next.

Here, as in Waiting for an Angel, Helon Habila emphasizes the power of the press to keep people honest—or more honest than they would be without reporters watching and reporting on their actions. Rufus, a young reporter with an uncertain job future, and Zaq, an alcoholic who was once one of the best reporters in the country, are searching for Isabel Floode, the wife of a British petroleum engineer, who has been kidnapped by rebels and, presumably, held for ransom. Nine days have passed since the two reporters and their boatman left Port Harcourt, and all the other journalists looking for her have given up, but these two continue to follow the river in a small canoe, looking for clues and trying to make contact with those who may be holding Mrs. Floode.

Adogbo, a stilt village

No one knows (or will say) how to reach the rebels, and no reliable demands have been made for ransom. As Rufus becomes frustrated by delays, the veteran Zaq must remind him to keep his eye on their real goal: “Forget the woman and her kidnappers for a moment. What we really seek is not them but a greater meaning. Remember, the story is not the final goal….The meaning of the story [is], and only a lucky few ever discover that.”

As they travel, the author uses Rufus as an intelligent, if sometimes callow, Everyman who appears to observe everything around him for the first time—abandoned villages, burned out villages, villages that have been bought and razed by the oil companies, and villages in which no one “knows” anything, caught between the militant rebels and the military. “The only way [these villages] could avoid being crushed out of existence was to pretend to be deaf and dumb and blind.” Torture for information is a common technique employed by both sides.

Throughout his travels, Rufus also reminisces about his own past and how he became a writer, broadening the scope of the action and giving more detail about how real people try to live real lives within a corrupt and treacherous environment. As Zaq once told him in a lecture in journalism school, “Journalists are conservationists…we scribble for posterity…[and] once in a while, maybe once in a lifetime, comes a transcendental moment, a great story only the true journalist can do justice to…” As the novel progresses, the reader observes Rufus maturing and coming to terms with his goals, even as he sees how much broader and more complex his subject is than what he had imagined. He begins to see the shades of gray which mark the work of true journalists. His interview with the husband of the kidnapped woman shows him the point of view of an oil engineer—and a new slant on the kidnapping—and also provides him the opportunity to discuss the horrors of the oil drilling within his own village, domestic details which give added power to the narrative.

Night Life, Bar Beach, Lagos

Because Zaq is twenty years older than Rufus, Zaq’s story, as it emerges, shows how Nigeria’s cultural values and its political history have changed from the 1980s through 1990s. And when the two journalists arrive at Irikefe, an island which has become a shrine to nature gods, tended by devoted “monks” who create wooden statues celebrating life, another view of the culture of local people emerges.

Habila writes efficiently and often descriptively, emphasizing the lives of individuals within a fraught environment while avoiding the temptation to turn the novel into a war story, however much conflict exists. His depiction of village life contrasts with that of the cities of Port Harcourt and Lagos, and the moments of horror cast the moments of kindness into sharper relief. Throughout, the emphasis is on individuals, and though most of them are not fully developed (nor do they need to be), they give a vivid portrait of real life in Nigeria, especially to readers who may be unfamiliar with Nigeria’s history and its current problems. The narrative, as it dips back and forth into the past, constantly broadens the picture of Nigerian life, and it is obvious that the author himself has taken to heart the Professor’s admonition to “Write only the truth.”

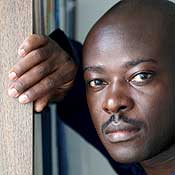

Photos, in order: The author’s photo by Jide Alakija is from http://marketplace.publicradio.org

Rufus and Zaq stop at a “stilt village,” known as Adogbo, on their trip upriver: http://www.nigerianfield.org

The photo of militants accompanies a story about the kidnapping of two children of a Nigerian, not British, employee of one of the oil companies. http://www.dailymail.co.uk

Night life in Bar Beach in Lagos, a sharp contrast to the scenes of village life on the river. http://www.localyte.com