Note: WINNER of innumerable prizes and often mentioned as a candidate for the Nobel Prize for Literature, Israeli author Amos Oz was the recent WINNER of Germany’s International Literature Prize for this novel.

“Here is a story from the winter days of the end of 1959 and the beginning of 1960. It is a story of error and desire, of unrequited love, and of a religious question that remains unresolved. Some of the buildings still bore the marks of the [Arab-Israeli] war that had divided [Jerusalem] a decade earlier. In the background you could hear the distant strains of an accordion or the plaintive sound of a harmonica from behind closed shutters.”

In the opening paragraph of this remarkable novel, Israeli author Amos Oz prepares the reader for some broad themes and provides tantalizing suggestions regarding a plot, based on “error,” “desire,” and “unrequited love.” He then calls to mind the Arab-Israeli War, and then, almost casually, adds that this story will also include an unresolved religious question, one which the author lets “float” for the rest of the opening chapter as he describes his main character, Shmuel Ash. A student in his mid-twenties, Ash is frustrated with his college thesis on “Jewish Views of Jesus,” and about to drop out of school; his commitment to the Socialist Renewal Group has gone awry; and the sweet emotionalism and the teary empathy he shows even for characters in mediocre movie plots have left him open to romantic disappointment. His girlfriend, in fact, “liked his bouncy spirit, his helplessness, and the exuberance that made her think of a friendly, high-spirited dog, always nuzzling you, demanding to be petted, and drooling in your lap.” She has, however, decided to accept a marriage proposal from her former boyfriend, “a specialist in rainwater collection.” And so Shmuel, “generous and brimming with goodwill… as soft as a woolen glove,” but who “never knew where he had put his other sock,” finds himself jilted and then out of college, his thesis, abandoned.

In the opening paragraph of this remarkable novel, Israeli author Amos Oz prepares the reader for some broad themes and provides tantalizing suggestions regarding a plot, based on “error,” “desire,” and “unrequited love.” He then calls to mind the Arab-Israeli War, and then, almost casually, adds that this story will also include an unresolved religious question, one which the author lets “float” for the rest of the opening chapter as he describes his main character, Shmuel Ash. A student in his mid-twenties, Ash is frustrated with his college thesis on “Jewish Views of Jesus,” and about to drop out of school; his commitment to the Socialist Renewal Group has gone awry; and the sweet emotionalism and the teary empathy he shows even for characters in mediocre movie plots have left him open to romantic disappointment. His girlfriend, in fact, “liked his bouncy spirit, his helplessness, and the exuberance that made her think of a friendly, high-spirited dog, always nuzzling you, demanding to be petted, and drooling in your lap.” She has, however, decided to accept a marriage proposal from her former boyfriend, “a specialist in rainwater collection.” And so Shmuel, “generous and brimming with goodwill… as soft as a woolen glove,” but who “never knew where he had put his other sock,” finds himself jilted and then out of college, his thesis, abandoned.

On the college bulletin board, he finds a notice advertising a job for a Humanities student willing to spend five hours each evening chatting with a seventy-year-old invalid who craves company. The notice indicates that the employer will provide housing for the person who accepts this job, but the new employee will have to agree to have no visitors and to keep confidential everything he learns about his employers. With nothing to lose, Shmuel accepts the job. As Oz develops the stories of these mysterious people and how they are connected, he also establishes deep-seated theological and historical conflicts which continue to plague the world, especially the Middle East, to the present day. What begins as a highly descriptive novel of the real world quickly blossoms into a grand exploration of the ideas and theological beliefs which are the bedrock of Christianity and Judaism, their history and cultures – a novel “writ large” in the best possible meaning of those words.

On the college bulletin board, he finds a notice advertising a job for a Humanities student willing to spend five hours each evening chatting with a seventy-year-old invalid who craves company. The notice indicates that the employer will provide housing for the person who accepts this job, but the new employee will have to agree to have no visitors and to keep confidential everything he learns about his employers. With nothing to lose, Shmuel accepts the job. As Oz develops the stories of these mysterious people and how they are connected, he also establishes deep-seated theological and historical conflicts which continue to plague the world, especially the Middle East, to the present day. What begins as a highly descriptive novel of the real world quickly blossoms into a grand exploration of the ideas and theological beliefs which are the bedrock of Christianity and Judaism, their history and cultures – a novel “writ large” in the best possible meaning of those words.

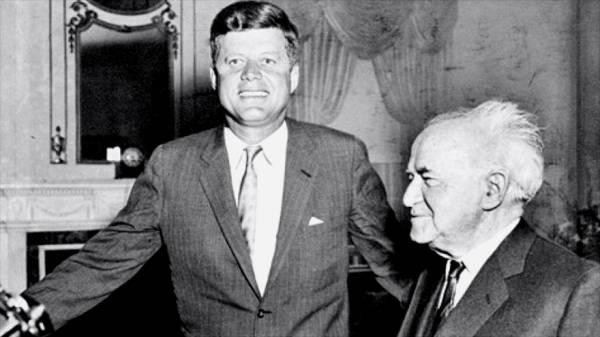

President John F. Kennedy meets with Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion in May, 1961. They meet at the Waldorf Astoria, not at the White House, due to the tensions between their countries.

Gershom Wald, the old man, and Atalia Abravanel, the woman in her mid-forties with whom he lives, become the characters through whom the past is channeled to Shmuel, but there are two other characters, invisible, who are at least as important. It gives away nothing to say that one of them, Gershom Wald’s son Micha, who died in the Arab-Israeli War, is a constant presence in this house. The other is Atalia’s father, Shealtil Abravanel, a lawyer whose ideals came into direct conflict with those of David Ben-Gurion, Israel’s first Prime Minister after the founding of the State of Israel in 1948. Abravanel had hoped that the Jews and the Arabs might form a Great Land of Israel, in which both groups would be able to live together, where each group could have their own cultural areas, and where they would share Jerusalem. The Zionist militarism which led to the establishment of the State of Israel was a disappointment to him and many others who had hoped for co-operation and peace between the groups. Abravanel, too, once lived in this house, which becomes a microcosm of the past, present, and the future of Israel since its founding.

Now, ten years later, forty-five-year-old Atalia Abravanel works as an “investigator” but otherwise lives a solitary life. Shmuel finds himself becoming attracted to her, and she sometimes flirts with him, though Wald constantly warns him that “she lets men who are fascinated by her get closer to her, then she drives them away… Atalia is always right …but being permanently in the right is like being scorched earth, isn’t that so?” Other young men, like Shmuel, have had the job that Shmuel has now, and it is clear that Atalia will never take Shmuel seriously, though she will suggest going on walks, to the movies, and even going to bed with him. The reader does not know until later in the novel what has made Atalia so bitter, and so vengeful. Vengeance, by definition, reflects the desire to punish someone for a betrayal, and Atalia’s need to punish clearly has deep-seated roots.

Marble statue of Jesus and Judas, beside the Scala Sancta in the Lateran Palace, one of the Pope’s homes in Rome.

The second – and by far the biggest and most startling – philosophical issue in this book connects Shmuel to past theological views of betrayal. Very early in his own college research, Shmuel wonders why, in all the writings he has seen about Jesus and His gospel, there is no mention of Judas Iscariot, for “if it had not been for Judas, there might not have been a crucifixion, and had there been no crucifixion, there would have been no Christianity.” As Shmuel later discovers, Rabbi Judah Arieh de Modena, a seventeenth century scholar, regards Judas as “the most enthusiastic of all the apostles,” the “first man who believed with total faith in Jesus’s divinity.” According to the rabbi, Judas believed that if Jesus were to leave Galilee and go to Jerusalem where he might be crucified, that “he would [later] drag himself down from the cross and stand whole and healthy at the foot of the cross. And so the Kingdom of Heaven would begin.” Judas’s faith never wavered, and when Jesus died, Judas was so distraught at bringing about His death that he went away and hanged himself. (See pp. 146 – 153 for this unforgettable passage.)

Amos Oz spent ten years writing this book. I spent a week reading it. Though I finished it three days ago, I am still digesting the magnificence of the writing, the ideas, the scope, and the implications of all that Amos Oz offers here. Though it is dense, it is also enlivening, and for an American audience, it provides historical context for some of the issues between the US and Israel in the present. The religious subject matter, new to me, was stunning, and the relationships between desire and error, and betrayal and vengeance, seen throughout, have never seemed so close.

Note: Sensitive and vibrant translation by Nicholas de Lange.

ALSO by Amos Oz: A PANTHER IN THE BASEMENT (on my All-Time Favorites list), MY MICHAEL, RHYMING LIFE AND DEATH, SCENES FROM VILLAGE LIFE, SOUMCHI, A TALE OF LOVE AND DARKNESS

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on http://forward.com/

President Kennedy meets with Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion at the Waldorf Astoria, May, 1961. Tensions were high between the US and Israel, so they did not meet at the White House. https://elmicrolector.org

Sunrise on Mount Zion: https://bonniewilks.com/

Marble statue of Jesus and Judas, beside the Scala Sancta in the Lateran Palace, one of the Pope’s residences in Rome: http://hackingchristianity.net/