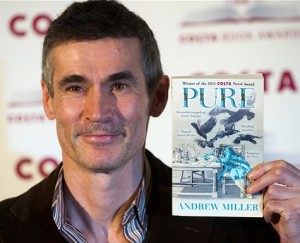

Note: This novel was WINNER of the Britain’s Costa Award for Best Novel in 2011. It has been SHORTLISTED for the prestigious IMPAC Dublin Award for 2013.

“[The cemetery] is poisoning the city. Left long enough, it may poison not just local shopkeepers but the king himself. The king and his ministers…It is to be removed. Destroyed. Church and cemetery. The place is to be made sweet again. Use fire, use brimstone. Use whatever you need to get rid of it.”

Writing some of the clearest, cleanest prose in recent memory, Costa Award winner Andrew Miller uses his pristine sentences and uncompromising descriptions with great irony as he illuminates the vile and stomach-turning conditions of a heavily populated area in central Paris. Set in 1785, just four years before the French Revolution, Miller’s main character, Jean-Baptiste Baratte, a young engineer from rural Belleme in Normandy, arrives in Paris, hoping for a job which will allow him to put his skills to use in ways not possible at home. Interviewed at Versailles and hired by a minister there, he learns that his job will be to empty the Cemetery of the Innocents in the heart of the city of its entire underground contents, and with over twenty burial pits located within a small, enclosed area, the work will be “both delicate and gross.” The entire neighborhood around the cemetery has become so putrid after the long use of this cemetery (and, more recently, the hurried interment of fifty thousand humans in less than a month in mass graves during the latest plague) that the stench permeates everything there – buildings, food, and ultimately people, their very breaths reeking of decay. Baratte’s assignment is to make the cemetery “new, pure,” in just one year.

Writing some of the clearest, cleanest prose in recent memory, Costa Award winner Andrew Miller uses his pristine sentences and uncompromising descriptions with great irony as he illuminates the vile and stomach-turning conditions of a heavily populated area in central Paris. Set in 1785, just four years before the French Revolution, Miller’s main character, Jean-Baptiste Baratte, a young engineer from rural Belleme in Normandy, arrives in Paris, hoping for a job which will allow him to put his skills to use in ways not possible at home. Interviewed at Versailles and hired by a minister there, he learns that his job will be to empty the Cemetery of the Innocents in the heart of the city of its entire underground contents, and with over twenty burial pits located within a small, enclosed area, the work will be “both delicate and gross.” The entire neighborhood around the cemetery has become so putrid after the long use of this cemetery (and, more recently, the hurried interment of fifty thousand humans in less than a month in mass graves during the latest plague) that the stench permeates everything there – buildings, food, and ultimately people, their very breaths reeking of decay. Baratte’s assignment is to make the cemetery “new, pure,” in just one year.

Despite the unusual and unsavory subject matter, Miller is careful to recreate the human side of the story – to make the reader empathize with Baratte, to see how important the job is to him, to show how he longs for acceptance, to appreciate his desire for love, and to understand how good he is at heart – and even a job as putrid this one quickly involves the reader in the story and its historical setting. Details about Paris in this pre-revolution time stick in the reader’s memory: an elephant, somewhere in Versailles, that exists on Burgundy wine; a revolutionary group devoted to the future – “indeed its vanguard” – that plasters graffiti about the church and aristocracy on walls and buildings; the harsh and uncertain lives of poor women and their children; the nearly hopeless lives of the miners with whom Baratte worked for two years in Valenciennes and whom he hires for the horrific job of digging on the site; and later, their differences in outlook from the masons he hires for additional on-site work.

Throughout the novel, Miller’s descriptive details are unforgettable and often symbolic: a dog who urinates on a vase in the waiting room at Versailles before Baratte’s interview, and the stain remaining on the parquet floor when he leaves; a priest described as “a big wingless bat in the dusk”; Parisian theatre-goers “fighting their way through the doors like scummed water draining out of a sink”; a man with eyes “like two black nails hammered into a skull; and an crazed old man “nude as a worm,” who begins to howl.

As Miller develops the story, his clever symbolism reveals simultaneously the state of mind of Baratte and the conditions in the country itself, foreshadowing the coming revolution through the eyes of Baratte. Very early in his work, Baratte recognizes that “Destroying the cemetery of the Innocents is to sweep away in fact not in rhetoric, the poisonous influence of the past.” When his friend Armand encourages him to commission a new, modern suit of clothes – a pistachio silk suit and a red damask “banyan” for evening – he is not completely comfortable with these accoutrements, since they smack of another class. The role of Heloise, a prostitute with a heart of gold and the intellect of a modern woman, is important in showing how indifferent the court is to the resilience and resourcefulness of, not only women, but of the talented and thwarted men of the country. The characters’ attitudes toward life, death, God, and the afterlife, if any, echo throughout the novel as the bodies are disinterred and cleaned for reburial in the catacombs beneath the city. The resentment of some of the population to this disinterment is also a factor in Baratte’s project, one which must be continued, regardless.

Baratte and guest attend a show at the elaborately gilded Odeon, built just two years before the time of this novel

As the removal of bones from the cemetery progresses, Baratte tries to accommodate the personal, emotional needs of his men, acting as a somewhat benevolent, though still strict, overseer. He gives them privileges unlike anything they ever had when working in the mines, and while this helps, it does not prevent assaults, including a life-threatening one on Baratte himself in his own quarters. A sexual assault by one of his men has disastrous effects, both on the woman involved and on the man himself, and when Baratte hires a group of stonemasons to help raze the church adjacent to the cemetery, he introduces a whole new culture to the group of miners that has been working for more than six months. Crises occur, and Baratte must deal with them with the limited knowledge and power he has, his honesty shining through, even when his sensitivity to some of the beliefs of his men is limited.

The removal of the cemetery led to the immediate building of this marketplace on the site. Some of Baratte’s masons were hired to work on the paving.

Ultimately, Miller succeeds in making this unlikely subject and its unusual characters both engaging and thought-provoking in ways not characteristic of the usual historical novel, requiring the reader to think beyond the limitations of most stories which are set two hundred fifty years earlier than the lives of the readers. Baratte himself learns from the year he spends in this thankless and miserable job, and he reflects the increasing awareness of a growing segment of the population as a whole that the life of the court of Versailles has reached the end of the line. At the conclusion of his job, he produces his final report for the minister and takes it to Versailles, his return to the palace filled with striking parallels and contrasts to the details of his arrival. Miller never overplays his conclusion, however, respecting the reader’s ability to fill in some of the blanks that make this novel so memorable. An unusual and beautifully written novel which shines new light on the horrors which incite revolution.

ALSO by Andrew Miller: INGENIOUS PAIN, OXYGEN, THE CROSSING

Photos, in order: The author’s photo, taken at his Costa Award ceremony, appears on http://www.telegraph.co.uk/

This early painting of the cemetery and Church of the Innocents is from http://en.wikipedia.org.

The green silk suit which Baratte has made would have resembled the one shown here: http://www.metmuseum.org

Baratte and a guest attend a show at the elaborately decorated Odeon Theatre, which was built two years before the opening of this novel. http://m.jaccede.com

The removal of the cemetery and Church of the Innocents led to the building of the market on the site. The pavement there was scheduled to be installed by some of the masons on Baratte’s project. Painting by John James Chalon, 1822: http://www.photos-galeries.com

ARC: Europa