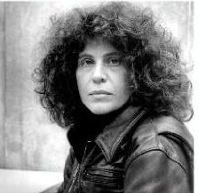

“As the ragged cavity [caused by the on-going removal of the temple at Abu Simbel] expanded, as the gaping absence in the cliff grew deeper, so grew Avery’s feeling they were tampering with an intangible force, undoing something that could never be produced or reproduced again. The Great Temple had been carved out of the very light of the river, carved out of a profound belief in eternity.”

Eleven year s after the publication of Fugitive Pieces, her only other novel (and winner of the Orange Prize), Anne Michaels has published a monumental philosophical novel which is also exciting to read for its characters and their conflicts. Complex and fully integrated themes form the superstructure of the novel in which seemingly ordinary people deal with issues of life and death, love and death, the primacy of memory, the search for spiritual solace, and the integrity of man’s relationships with the earth and the water that makes the earth habitable—huge themes and huge scope, reflecting huge literary goals. And Michaels is successful, not just in dealing with the big issues and themes affecting mankind itself, but in bringing them to life through individuals who muddle along, seeking some level of personal connection with the world while trying to appreciate life’s mysteries.

s after the publication of Fugitive Pieces, her only other novel (and winner of the Orange Prize), Anne Michaels has published a monumental philosophical novel which is also exciting to read for its characters and their conflicts. Complex and fully integrated themes form the superstructure of the novel in which seemingly ordinary people deal with issues of life and death, love and death, the primacy of memory, the search for spiritual solace, and the integrity of man’s relationships with the earth and the water that makes the earth habitable—huge themes and huge scope, reflecting huge literary goals. And Michaels is successful, not just in dealing with the big issues and themes affecting mankind itself, but in bringing them to life through individuals who muddle along, seeking some level of personal connection with the world while trying to appreciate life’s mysteries.

Avery Escher is a young engineer in 1964 when he and his wife Jean travel to Abu Simbel, where he is charged with the task of helping to remove the Great Temple of Abu Simbel and reconstruct it in the cliff sixty feet higher. Gushing water, which will be released when the Aswan Dam is finished, will flood the area where the temple lies, and the new Lake Nasser will cover all the land downstream. The reconstruction is planned to be so seamless that no one will be able to tell that the temple and its ancient monuments have been taken apart, block by block, and put back together again. Yet, as he works on the site, slowly and  meticulously, Avery feels ashamed, feeling that “Holiness was escaping under the [workers’] drills,” and he wonders “Can you move what was consecrated?” Surprised at his own response, because he had expected that the salvage would be an “antidote” to the “despair of dam-building,” he comes to believe, instead, that “the reconstruction was a further desecration, as false as redemption without repentance.”

meticulously, Avery feels ashamed, feeling that “Holiness was escaping under the [workers’] drills,” and he wonders “Can you move what was consecrated?” Surprised at his own response, because he had expected that the salvage would be an “antidote” to the “despair of dam-building,” he comes to believe, instead, that “the reconstruction was a further desecration, as false as redemption without repentance.”

All the Nubian people who have lived in the area below the dam for tens of generations have been relocated (or more accurately, dislocated) to a site a thousand miles away, along with their animals and all their possessions, but they are bereft. They have not been able to take with them the places where their dead are buried, where they have loved and worked the land, where they have worshipped, and where their memories and their very souls reside. The new cement-block village, erected in a dry, treeless plain, bears no resemblance to the home where they have always had their roots. All of Nubia has been displaced by the damming of the Nile and the building of a lake, named for a modern political leader, which has destroyed their own ancient history.

Abu Simbel Temple

This is not the first time Avery has been exposed to the dislocation of long-time residents through the building of dams and lakes. His father, William Escher, was an engineer on the Canadian project to build the St. Lawrence Seaway from the Atlantic Ocean to the Great Lakes, which involved the flooding of ten Canadian villages through the building of Lake St. Lawrence. Stories about the Eschers’ displaced family friends are touching and bring the thematic development—and the sadness—down to a more intimate personal level.

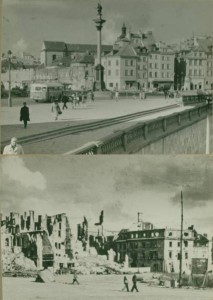

A third thread involving man’s desire to honor and preserve the past, though the present has changed it irrevocably, takes place in Warsaw, following World War II, after the departure of the German and Russian occupiers. The city decided to rebuild its central historical core to look exactly the way it did before the war, using plans hidden and preserved by polytechnic students during the war and historical artifacts scavenged from the rubble. The reconstructed city, thought “successful” by its builders, never felt real to many of the people who lived there, however—its heart was missing, as were its memories—along with almost all its Jewish people. As one Polish character mourns, “I do not know if we belong to the place where we are born or the place where we are buried.”

Eisenhower Lock, St. Lawrence Seaway

Within this fully developed thematic framework, filled with symbols, Anne Michaels creates a passionate love story between Avery Escher and his wife Jean, and a generational saga about Avery Escher and his family and friends, alternating their personal stories and their personal relationships to earth and water with the grand stories from Egypt, the St. Lawrence Valley, and Poland. Avery and his family have lived along the St. Lawrence River and its subsequent Seaway, empathizing with those displaced, though Avery’s father actively contributed to it. Jean has faced personal displacement following the deaths of her parents. A botanist, Jean collects seeds and seedlings, transplants the garden that once belonged to her mother, grafts trees to preserve them, and, during a particularly difficult time in her relationship with Avery, plants flowers at night in public places where they will surprise visitors who have not expected them.

Reconstructed Warsaw

While Avery is dealing with technology and man’s desire to improve nature and reconstruct the past artificially, Jean is preserving and growing new life in the land which nurtures it. Not surprisingly, their love is tested to the limits by their different understanding of man’s relationship with nature and the interconnections of land and water to memory, the past, and ultimately the present and future. “I think,” Avery says early in the novel, “we each have only one or two philosophical or political ideas in our life, one or two organizing principles during our whole life, and all the rest falls from there.” Fortunately, mankind—and individuals—are capable of learning and changing. “Regret is not the end of the story,” we learn. “It is the middle of the story.”

Michaels’s talent as a poet is obvious in her gorgeous ruminations about the meaning of love and life, and in her evocative, unique imagery, but the beauty of the language is matched by the richness of the novel’s underlying concepts, which give depth and significance to this challenging and satisfying novel. Raising fascinating questions, Michaels piques the imagination and guides the reader into new realms of thought.

Notes: The author’s photo appears on her Amazon Author page.

The photo of Abu Simbel comes from http://travel.nationalgeographic.co.in

A ship enters the St. Lawrence Seaway system through the Eisenhower Lock at Massena: http://www.bcnys.org

The final photo shows Warsaw during its destruction in the bottom of the picture and after reconstruction at the top: http://www.unesco-ci.org