Note: This novel was WINNER of the Whitbread Award for Best Novel in 1996.

“[As the Titanic was being evacuated] the journalist stood and shook us both by the hand. ‘It’s been an interesting trip,’ he observed. ‘I doubt we’ll see another one like it.’ ”

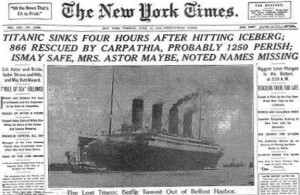

My mother was born on the day that the Titanic hit the iceberg – April 14, 1912 – and every member of our family has always known that the ship sank a few hours later, on April 15, 1912. When she died in 2010, four months after her ninety-eighth birthday, my mother had outlived every survivor of that wreck. With the centennial of the Titanic disaster now approaching, Europa Editions has re-published Beryl Bainbridge’s 1996 novel Every Man for Himself, the award-winning novel of the ship’s doomed voyage, a concise and “awe-full” story of life and death, primarily among the first class passengers, most of them super-rich industrialists and their heirs. A nephew of J. P. Morgan, recently graduated from Harvard, tells the story, providing a new, first person vision of the ship’s lively social life from April 12 through the ship’s demise on April 15. Fictional characters, who feel real, mix with real characters whose presence on the ship is well documented, as Bainbridge recreates the giddy excesses and the sense of entitlement exhibited by the top deck passengers.

My mother was born on the day that the Titanic hit the iceberg – April 14, 1912 – and every member of our family has always known that the ship sank a few hours later, on April 15, 1912. When she died in 2010, four months after her ninety-eighth birthday, my mother had outlived every survivor of that wreck. With the centennial of the Titanic disaster now approaching, Europa Editions has re-published Beryl Bainbridge’s 1996 novel Every Man for Himself, the award-winning novel of the ship’s doomed voyage, a concise and “awe-full” story of life and death, primarily among the first class passengers, most of them super-rich industrialists and their heirs. A nephew of J. P. Morgan, recently graduated from Harvard, tells the story, providing a new, first person vision of the ship’s lively social life from April 12 through the ship’s demise on April 15. Fictional characters, who feel real, mix with real characters whose presence on the ship is well documented, as Bainbridge recreates the giddy excesses and the sense of entitlement exhibited by the top deck passengers.

The speaker, an orphan who never knew his parents, has been raised by his aunt and his cousin Sissy, but he has always thought that he was special. “I don’t care to be misunderstood,” he avers. “I’m not talking about intellect or being singled out for great honours, simply that I was destined to be a participant rather than a spectator of singular events,” a statement that reveals more about his attitudes than he probably intends. After prep school and Harvard, and an active social life befitting a member of J. Pierpont Morgan’s family, he began work for Thomas Andrews, the naval architect in charge of the plans for the Titanic, and indirectly for his cousin J. P. “Jack” Morgan, one of the owners of the White Star line which commissioned the ship. Though his contribution was small, young Morgan, interested in the Titanic, makes the inaugural trip on the Titanic with friends, enjoying all the amenities of the first class passengers. Architect Thomas Andrews is present on board, as is J. Bruce Ismay, the chairman and managing director of the White Star line, though J.P. Morgan, Henry Clay Frick, and George W. Vanderbilt, who had planned to sail with the ship, had a change of plans before the ship sailed. Still, John Jacob Astor and his young bride Madeleine, Benjamin Guggenheim, Isador Straus and his wife, and members of the Rothschild and Widener family provide plenty of glamour.

The speaker, an orphan who never knew his parents, has been raised by his aunt and his cousin Sissy, but he has always thought that he was special. “I don’t care to be misunderstood,” he avers. “I’m not talking about intellect or being singled out for great honours, simply that I was destined to be a participant rather than a spectator of singular events,” a statement that reveals more about his attitudes than he probably intends. After prep school and Harvard, and an active social life befitting a member of J. Pierpont Morgan’s family, he began work for Thomas Andrews, the naval architect in charge of the plans for the Titanic, and indirectly for his cousin J. P. “Jack” Morgan, one of the owners of the White Star line which commissioned the ship. Though his contribution was small, young Morgan, interested in the Titanic, makes the inaugural trip on the Titanic with friends, enjoying all the amenities of the first class passengers. Architect Thomas Andrews is present on board, as is J. Bruce Ismay, the chairman and managing director of the White Star line, though J.P. Morgan, Henry Clay Frick, and George W. Vanderbilt, who had planned to sail with the ship, had a change of plans before the ship sailed. Still, John Jacob Astor and his young bride Madeleine, Benjamin Guggenheim, Isador Straus and his wife, and members of the Rothschild and Widener family provide plenty of glamour.

The clear demarcation between the elite in first class and the lower, “ordinary” classes is obvious from the outset. As Morgan himself says, “I could pick out fifty or more men [here] that I’ve known half my life and Lord knows how many others I’ve shared a dinner table with in half the capitals of Europe. There isn’t a photograph taken from here to the Nile that doesn’t feature twenty or more of us lined up to watch the dicky-bird…Why half the older men here have even shared the same mistresses.” The classes never mix.

Bainbridge’s trademark wit and her perfect, pointed descriptions keep the novel moving, even as the biggest, most obvious drama remains in the future, and some issues regarding the ship itself are revealed – the seamen are required to work double shifts to keep the coal-fired engines running at peak in order to try to break speed records from Southampton to New York, something Morgan discovers on a trip to the hold to see a friend’s new car. A fire in the #10 coal bunker has been blazing for days in an area lined with iron and not reinforced steel. There are not enough lifeboats and the crew has had little or no practice lowering the existing lifeboats into the ocean. Still the party goes on, the passengers naïve and oblivious to these dangers.

As the passengers engage in their own personal mini-dramas, Bainbridge provides sly descriptions of these characters, providing color and a cinematic quality to the scenes. A woman arrives at dinner, escorted by “a pink porpoise of a man.” The “unsinkable Molly Brown,” described here simply as “Mrs. James Brown,” wears a gigantic hat “on whose brim languished an entire stuffed bird.” Morgan describes dancing with one woman as being “like holding cut glass…she made him feel he left finger marks.” A man who expounds on the “two impulses,” hunger and sex, is put in his place when the speaker comments that “There is another impulse. Boredom. Which is never absent when you’re around.” In describing Chairman Bruce Ismay of the White Star line, Morgan notes that “unlike most Englishmen, he lacked apathy.”

As the passengers engage in their own personal mini-dramas, Bainbridge provides sly descriptions of these characters, providing color and a cinematic quality to the scenes. A woman arrives at dinner, escorted by “a pink porpoise of a man.” The “unsinkable Molly Brown,” described here simply as “Mrs. James Brown,” wears a gigantic hat “on whose brim languished an entire stuffed bird.” Morgan describes dancing with one woman as being “like holding cut glass…she made him feel he left finger marks.” A man who expounds on the “two impulses,” hunger and sex, is put in his place when the speaker comments that “There is another impulse. Boredom. Which is never absent when you’re around.” In describing Chairman Bruce Ismay of the White Star line, Morgan notes that “unlike most Englishmen, he lacked apathy.”

When the ship hits the iceberg, it is regarded primarily as a momentary interruption, perhaps even a hoax, and Bainbridge lets that feeling remain, even as Morgan is urged by a steward to leave his cabin and go up on deck wearing heavy clothes. “I swaggered rather than walked…How my aunt would throw up her hands when I shouted the details of my midnight adventure! Why, as long as I wrapped up well it would be the greatest fun in the world.” The fact that this took place at 11:40 p.m., after the first class passengers had spent the night drinking, goes a long way toward explaining some of the conduct which occurs in this emergency. The ship sank only two hours and forty minutes after it struck. Ultimately, the passengers, whom we have had a chance to get to know a bit (as well as one can know arrogant characters who obey their own private code) and their responses to the emergency become the main story, and readers will be appalled by the loss of lives which might have been saved, even at that late hour, had more care been taken to save those “below decks.” Bainbridge creates no scapegoats, however, and says barely a word about the behavior of the captain, Edward J. Smith (“What was Smith expected to do?”) or J. Bruce Ismay, the highest ranking White Star official aboard.

When the ship hits the iceberg, it is regarded primarily as a momentary interruption, perhaps even a hoax, and Bainbridge lets that feeling remain, even as Morgan is urged by a steward to leave his cabin and go up on deck wearing heavy clothes. “I swaggered rather than walked…How my aunt would throw up her hands when I shouted the details of my midnight adventure! Why, as long as I wrapped up well it would be the greatest fun in the world.” The fact that this took place at 11:40 p.m., after the first class passengers had spent the night drinking, goes a long way toward explaining some of the conduct which occurs in this emergency. The ship sank only two hours and forty minutes after it struck. Ultimately, the passengers, whom we have had a chance to get to know a bit (as well as one can know arrogant characters who obey their own private code) and their responses to the emergency become the main story, and readers will be appalled by the loss of lives which might have been saved, even at that late hour, had more care been taken to save those “below decks.” Bainbridge creates no scapegoats, however, and says barely a word about the behavior of the captain, Edward J. Smith (“What was Smith expected to do?”) or J. Bruce Ismay, the highest ranking White Star official aboard.

Though some readers may be “Titanic’d” to death by the number of books and articles written about this disaster for its centennial, along with new National Geographic photographs and the 1997 film being released in 3D on April 3, 2012, Bainbridge’s contribution is a worthy and beautifully written study – witty, insightful, and consummately ironic. Here she recreates an elite group which includes a few passengers who may sense, if not believe, that “there was something dishonourable in survival.”

Though some readers may be “Titanic’d” to death by the number of books and articles written about this disaster for its centennial, along with new National Geographic photographs and the 1997 film being released in 3D on April 3, 2012, Bainbridge’s contribution is a worthy and beautifully written study – witty, insightful, and consummately ironic. Here she recreates an elite group which includes a few passengers who may sense, if not believe, that “there was something dishonourable in survival.”

Also by Bainbridge: THE GIRL IN THE POLKA DOT DRESS

Also about the Titanic: THE MIDNIGHT WATCH: the Titanic and the Californian by David Dyer

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on http://www.guardian.co.uk

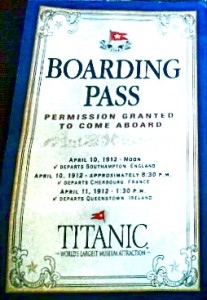

The boarding pass is from http://lifescoffeebreak.wordpress.com

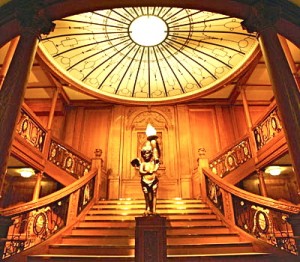

The Grand Staircase of the Titanic has been reproduced at the Raffles Hotel, Singapore: http://adventuresofprincessmitzi.blogspot.com

A first class cabin appears here: http://picturesofthetitanic.net/Titanic-Interior.html

The headline from the New York Times is from http://findmaritimejobs.com

A list of all passengers on the Titanic and their fates may be found at the bottom of this Wiki entry: http://en.wikipedia.org