“On Wednesday 23rd March 1983 there appeared in the Guardian the following report:

‘An inquest is to be held on the two elderly women whose bodies were found on Monday in the dilapidated North London house they shared with a man who was the brother of one of them and the brother-in-law of the other. Postmortem examinations yesterday revealed that they had both died from natural causes – but that the older woman had been dead for up to a year.’ ”

No one incorporates black, ironic humor into novels about earnest, often batty, elderly people better than the British. Gerard Woodward in A Curious Earth; Jane Gardam, especially in Queen of the Tambourine; Barbara Pym in Quartet in Autumn; and Stephen Benatar in Wish Her Safe at Home all provide ironic and twisted pictures of end of life issues as they affect the main characters and those around them. Benatar pays special attention to characters who are dealing with significant emotional stresses, and his novels are filled with psychological insights and feelings the reader understands, even as his mordant wit draws the characters to the edge, allowing the reader to watch them cross the line into darker and darker worlds of their own.

No one incorporates black, ironic humor into novels about earnest, often batty, elderly people better than the British. Gerard Woodward in A Curious Earth; Jane Gardam, especially in Queen of the Tambourine; Barbara Pym in Quartet in Autumn; and Stephen Benatar in Wish Her Safe at Home all provide ironic and twisted pictures of end of life issues as they affect the main characters and those around them. Benatar pays special attention to characters who are dealing with significant emotional stresses, and his novels are filled with psychological insights and feelings the reader understands, even as his mordant wit draws the characters to the edge, allowing the reader to watch them cross the line into darker and darker worlds of their own.

Sometimes described as “the best British writer that no one has ever heard of,” Benatar, now in his mid-seventies, has his own unusual story. Published by several noted publishing houses in England during the 1980s, Benatar quickly discovered that even though he won awards and his books were nominated for prizes, that his publishers did not promote or sell his books – that if his books were to sell, he had to do it himself. He ended his relationship with mainstream publishers, formed his own company to publish his books, and has been hand selling them, primarily at Waterstone’s in London, on weekends for thirty years since. The New York Review of Books recently republished his 1981 novel, Wish Her Safe at Home, after Edwin Franks, the NYRB managing editor, accidentally ran into the author when the author was returning some unused wine after a book launch and engaged him in con versation. Now When I Was Otherwise, Benatar’s third novel, written in 1983, has also been republished in England this past spring by Capuchin Classics. With a first paragraph as dramatic and ironic as the one quoted above, it is easy to see why Benatar succeeds in selling fifty to a hundred books each weekend.

versation. Now When I Was Otherwise, Benatar’s third novel, written in 1983, has also been republished in England this past spring by Capuchin Classics. With a first paragraph as dramatic and ironic as the one quoted above, it is easy to see why Benatar succeeds in selling fifty to a hundred books each weekend.

The three people mentioned in the opening paragraph, including the two dead women, are Dan Stormont, a seventy-six-year-old widower, whose German wife Erika has passed away long ago; his sister Marsha Poynton, age sixty, a divorcee with two sons who live far away; and Daisy Stormont, their sister-in-law, around whom all the action turns, the widow of Henry Stormont, Dan’s brother. Daisy, an active and lively flirt with great appeal to men, at least in her early days, has kept her age secret for her entire life, and most women are convinced that she is at least fifteen years older than she says she is, which would put her in her eighties at the time of her death. In fact, it was her age which made Henry’s mother Florence object to Daisy’s marriage to the naive Henry when he was in his early twenties, since Florence assumed Daisy to be in her late thirties then. Daisy herself claimed to be only two years older than Henry, and she blames Florence’s attitudes for forever tainting Daisy’s relationship with the family.

The novel starts at the end and works its way back to the beginning, jumping back and forth among time frames as the backgrounds and the entire histories of each character are laid bare. Often information about one character is conveyed by another, usually Daisy, from her own point of view, and Benatar is absolutely brilliant at writing dialogue which reveals character, attitudes, and information simultaneously. Daisy has a knack for saying exactly the wrong thing at the wrong time, while seeming to be ingenuous and innocent, and the reader quickly believes that no one could be so insensitive by accident. In short order Daisy alienates everyone, works her wiles on more than one man at a time, turns characters against each other, and causes some to question their own sanity, a problem that only increases when she moves in with Dan and Marsha in their somewhat run-down, “three bedroom, semi-detached” house in Hendon, outside of London.

The novel starts at the end and works its way back to the beginning, jumping back and forth among time frames as the backgrounds and the entire histories of each character are laid bare. Often information about one character is conveyed by another, usually Daisy, from her own point of view, and Benatar is absolutely brilliant at writing dialogue which reveals character, attitudes, and information simultaneously. Daisy has a knack for saying exactly the wrong thing at the wrong time, while seeming to be ingenuous and innocent, and the reader quickly believes that no one could be so insensitive by accident. In short order Daisy alienates everyone, works her wiles on more than one man at a time, turns characters against each other, and causes some to question their own sanity, a problem that only increases when she moves in with Dan and Marsha in their somewhat run-down, “three bedroom, semi-detached” house in Hendon, outside of London.

If Hitchcock were to make a film, Bette Davis would have been a shoo-in to play Daisy, though Daisy shares so many characteristics with Scarlett O’Hara that Vivian Leigh would have been a contender, too. At one point, Daisy wonders aloud if the marriage of Marsha and Andrew will last, and when challenged by Dan’s wife Erika, she says, “ ‘He strikes me as having something more between the eyes than she has; and I’ve often thought that it must be pure hell for a man with any sort of spark in him to be chained to an uninteresting woman. Beauty isn’t everything, you know. Although I daresay it helps,’ she added, looking at Erica reflectively.”

Appalled, the unflappable Erika responds, “Can this be a record? You have insulted me; you have insulted your mother-in-law; you have insulted your sister-in-law. I don’t know whether you’ve insulted Dan – but what is worse – far, far worse – you have actually managed to belittle him in front of me. I would have thought that was impossible. I believe that I should offer my congratulations.”

Page after page of similar dialogue initiated by Daisy reveals Marsha’s marriage and divorce and her later relationships with her sons; Dan’s marriage to Erika; and Daisy’s own marriage, widowhood, and flirtations. The roles each takes within the threesome at the house, the resentments caused by Daisy and exploited by her, and the deliberate hurts she causes in order to get her own way are examined leading up to the demise of the two women. Because everyone will be able to imagine someone acting like Daisy, the book feels true to life, no matter how bizarre Daisy becomes. Always there is a casual wittiness to the scenes which keeps the reader simultaneously amused and horrified by her behavior. Those who enjoy offbeat and darkly humorous novels will find this one a classic, the ending especially memorable.

ALSO by Benatar: WISH HER SAFE AT HOME

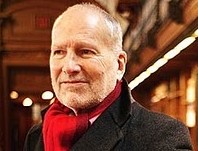

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on http://www.firsteditionpress.co.uk

Dan, Marsha, and Daisy might have lived in a “3 BR semi-detached” house similar to this one in Hendon. http://www.findaproperty.com

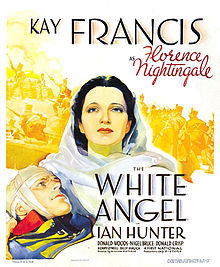

In one scene of marvelous double irony, Dan compares Daisy to Florence Nightingale in The White Angel. She is outraged: “I take it as very little compliment to be compared to a liar, a bully, a hypocrite, a busybody, an egoist, a betrayer….” Benatar’s genius for character and dark humor never end. The poster is from http://en.wikipedia.org