Note: Daniel Sada was WINNER of Mexico’s National Prize for Arts and Sciences (for Literature) in 2011.* This novel was WINNER of Mexico’s prestigious Herralde Prize in 2008.

“Renata and Mireya: heaven and hell, sanctity and sin, eternal and circumstantial, ruthless struggle and mere toy, but only one really deep intersection, an arid depth, and therein the absurd.”

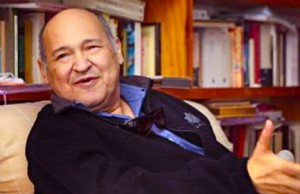

Much admired by both Roberto Bolano, who said, “Of my generation I most admire Daniel Sada,” and by Carlos Fuentes, who said that Daniel Sada “will be a revelation for world literature,” Mexican author Daniel Sada has now been published in English for the first time by Graywolf Press. Almost Never, “a Rabelaisian tale of lust and longing,” provides a bawdy and mildly satiric look at the whole concept of machismo as it exists in the mid-1940s in Mexico. Sada’s main character, Demetrio Sordo, almost thirty when the novel opens in 1945, grew up in rural Parras in northern Mexico, but he has recently been living near Oaxaca in southern Mexico, working six or seven days a week as an agronomist in charge of a large ranch. Bored by the usual nightly “entertainments” of “dominoes in seedy dives,” dull strolls for a mile or two followed by a cup of coffee, he finally concludes that “sex was the most obvious option.” Taking a taxi to a local brothel, he meets the beautiful brunette Mireya, revealing his personal charm by introducing himself with “Hey, you, come on already, let’s go to bed.”

Much admired by both Roberto Bolano, who said, “Of my generation I most admire Daniel Sada,” and by Carlos Fuentes, who said that Daniel Sada “will be a revelation for world literature,” Mexican author Daniel Sada has now been published in English for the first time by Graywolf Press. Almost Never, “a Rabelaisian tale of lust and longing,” provides a bawdy and mildly satiric look at the whole concept of machismo as it exists in the mid-1940s in Mexico. Sada’s main character, Demetrio Sordo, almost thirty when the novel opens in 1945, grew up in rural Parras in northern Mexico, but he has recently been living near Oaxaca in southern Mexico, working six or seven days a week as an agronomist in charge of a large ranch. Bored by the usual nightly “entertainments” of “dominoes in seedy dives,” dull strolls for a mile or two followed by a cup of coffee, he finally concludes that “sex was the most obvious option.” Taking a taxi to a local brothel, he meets the beautiful brunette Mireya, revealing his personal charm by introducing himself with “Hey, you, come on already, let’s go to bed.”

Demetrio’s increasingly adventuresome relationship with Mireya, explicitly described, becomes more and more obsessive as he hastens to visit her as often as possible over the next few weeks. The visits come to a temporary stop, however, when he receives a letter from his mother in Parras, asking him to come home at Christmas to accompany her to a wedding in Sacramento, even farther away to the north. As Demetrio’s trip will be over eight hundred miles through rural countryside, he will need to spend three days traveling there and three days back, with only one day at the wedding itself. Demetrio has no car or truck, and there are few paved roads. At the wedding in Sacramento, however, he meets and falls instantly in love with the beautiful, virginal Renata Malgarejo, so closely tied to the local culture of virginity that when he uses the pronoun “tu,” in telling her he will write to her from Oaxaca, she is shocked by his “familiarity.” She may allow the use of “tu” next time he visits, she says—on his vacation in August, nine months from then. He may even be allowed to hold her hand.

days traveling there and three days back, with only one day at the wedding itself. Demetrio has no car or truck, and there are few paved roads. At the wedding in Sacramento, however, he meets and falls instantly in love with the beautiful, virginal Renata Malgarejo, so closely tied to the local culture of virginity that when he uses the pronoun “tu,” in telling her he will write to her from Oaxaca, she is shocked by his “familiarity.” She may allow the use of “tu” next time he visits, she says—on his vacation in August, nine months from then. He may even be allowed to hold her hand.

Upon his return to the Oaxaca area, Demetrio and Mireya resume their relationship, but eventually she demands, “Get me out of this hellhole. I’m sick of being a slave to pleasure. I want to give myself to you, be faithful to you, have a family…I love you.” Demetrio, however, temporizes, saying that he is saving his money for a down payment on a house, that “I’m thinking about buying a palace. You deserve nothing less….” Faced with one woman who will do literally anything for him and who wants to get married right away, and another woman whom he has never even kissed and who plays the ultimate “hard-to-get” role, Demetrio faces a rare set of challenges, determined to get what he wants from both.

less….” Faced with one woman who will do literally anything for him and who wants to get married right away, and another woman whom he has never even kissed and who plays the ultimate “hard-to-get” role, Demetrio faces a rare set of challenges, determined to get what he wants from both.

In a slangy and breezy tone, the author develops his plot with more and more complications, clearly having fun with his audience at Demetrio’s expense and showing him to be both boorish and selfish, manipulating everyone around him—all of his victims women. At the same time, the author clearly understands Demetrio and is never harsh in his judgment of him. Demetrio is as much a product of his time as Renata and Mireya are, and as the novel’s chronology progresses from 1945 through 1947, with the country’s increasing industrialization, the migration of the rural population to the cities, new opportunities for young men to make money in new kinds of jobs, and improvements in transportation, Demetrio becomes emblematic o f a whole generation of young men for whom the sky seems to be the limit. The biggest danger, of course, is that these young men, including Demetrio, are actually inexperienced and naïve to the ways of the outside world, potential victims of other men who are more clever, more powerful, or more worldly, just as the women are victims of the men who have been dominating them socially and sexually for generations.

f a whole generation of young men for whom the sky seems to be the limit. The biggest danger, of course, is that these young men, including Demetrio, are actually inexperienced and naïve to the ways of the outside world, potential victims of other men who are more clever, more powerful, or more worldly, just as the women are victims of the men who have been dominating them socially and sexually for generations.

Sada is a master of language, and though his characters are, of necessity, somewhat caricatured as he pokes fun at them, they are lively and full of personal quirks. Peripheral characters, like Dona Telma, Demetrio’s mother, and Dona Zulema, his aunt (“the treacle tornado”), have stories which give depth to the author’s revelations about life and love, and Renata’s relationship with her domineering mother is an absolute classic. Demetrio’s dreams reveal that he does have a conscience, even when he commits boorish acts to extricate himself from complications he has never expected. His courtship of Renata, an exercise in frustration, has moments of high humor, and his agony at the slow pace of the relationship is matched, at times, by the reader’s own impatience. When Demetrio finally, in rebellion, begins to think of the whore Mireya as an “awesome saint…sexual saint, embossed upon the always-changing great beyond” and refers to her as “most holy Mireya,” the reader understands his state of mind.

The story with all its complications and bawdy language mocks the pretensions of its characters at the same time that it explains and even, in some cases, tries to justify them in terms of the social context of the period. The action is often absurd and the characters’ behavior outrageous. The language and sexual imagery are crude, and some readers will find them at least as vulgar as Demetrio is, something the author, no doubt, intended. Translator Katherine Silver deserves much credit for translating this novel and maintaining its tone, with a only few minor missteps (a character told to “suck it up,” someone referred to as “screwed up”), which seemed jarring for a novel set in the mid-1940s. Daniel Sada, whose novels have been, until now, unknown to the English-speaking world, should become a major “new” Mexican author, receiving the praise he deserves here for works of which we have been ignorant until now.

The story with all its complications and bawdy language mocks the pretensions of its characters at the same time that it explains and even, in some cases, tries to justify them in terms of the social context of the period. The action is often absurd and the characters’ behavior outrageous. The language and sexual imagery are crude, and some readers will find them at least as vulgar as Demetrio is, something the author, no doubt, intended. Translator Katherine Silver deserves much credit for translating this novel and maintaining its tone, with a only few minor missteps (a character told to “suck it up,” someone referred to as “screwed up”), which seemed jarring for a novel set in the mid-1940s. Daniel Sada, whose novels have been, until now, unknown to the English-speaking world, should become a major “new” Mexican author, receiving the praise he deserves here for works of which we have been ignorant until now.

*Author Daniel Sada died on Nov. 18, 2011, at age 58 after a long illness, just hours after the Government of Mexico granted him the National Prize of Sciences and Arts 2011 (for Literature).

ALSO by Sada: ONE OUT OF TWO

Photos, in order: The author’s photo is from http://www.tuteve.tv

Parras appears on this map (with Sacramento to the north) from http://inexplicata.blogspot.com

The church in Sacramento, which Renata attends, appears on http://www.tourbymexico.com

The Mexican pool hall depicted here is probably similar to the one that Demetrio eventually builds: http://www.justwalkedby.com