“As for the [missing woman’s] fate, the [police] argued, a body would turn up. The sea would spit it out, a hiker would stumble across it in the hills, a farmer would unearth it while plowing his field. That was the way it was on the island. Corsica always gave up its dead.”

An escape novel by best-selling author Daniel Silva always seems to be part of my summer reading list, and after looking at the dates for Silva’s novels, it is easy to see why. Of the twenty novels listed on Amazon (some of them duplicates in different editions), fifteen have been published during the summer months. Only five have been published in the winter, all in January or February, and all between 2003 and 2006, in the years before Silva became the huge, popular success that he is now. This latest book, The English Girl is another good book for summer reading – though not as interesting or challenging as his previous novel, The Fallen Angel, which dealt with on-going Arab-Israeli conflicts, a planned terrorist attack on an Israeli site in Europe, and the possibility that there is a very early Jewish temple built underneath the al-Aqsa Mosque on the Temple Mount. Silva’s own conclusions regarding the status of Israel and the Middle East in general, including the effects of the Egyptian uprising, also give immediacy and dramatic tension to that novel and its subject matter.

An escape novel by best-selling author Daniel Silva always seems to be part of my summer reading list, and after looking at the dates for Silva’s novels, it is easy to see why. Of the twenty novels listed on Amazon (some of them duplicates in different editions), fifteen have been published during the summer months. Only five have been published in the winter, all in January or February, and all between 2003 and 2006, in the years before Silva became the huge, popular success that he is now. This latest book, The English Girl is another good book for summer reading – though not as interesting or challenging as his previous novel, The Fallen Angel, which dealt with on-going Arab-Israeli conflicts, a planned terrorist attack on an Israeli site in Europe, and the possibility that there is a very early Jewish temple built underneath the al-Aqsa Mosque on the Temple Mount. Silva’s own conclusions regarding the status of Israel and the Middle East in general, including the effects of the Egyptian uprising, also give immediacy and dramatic tension to that novel and its subject matter.

The English Girl, by contrast, feels much more “domestic,” concerning itself for much of the book with the kidnapping of a young woman who has been the lover of the Prime Minister of England, a circumstance which the prime minister’s political friends want resolved privately and as quietly as possible. Gabriel Allon, an Israeli art restorer who also works for the Israeli secret intelligence agency, has connections to intelligence services throughout the world as a result of his extensive international work, and when he is contacted by the deputy director of MI5 in England, he agrees to try to find and free Madeline Hart, the woman being held hostage in some unknown place. Traveling from Israel to Paris, then to Corsica, where he connects with Don Anton Orsati, a professional assassin who manages a whole “family” of assassins for hire, Allon eventually follows a trail to Marseilles and to a villa occupied by “the Englishman,” Christopher Keller. A renegade SAS veteran and the only person in his unit to survive a friendly fire accident during Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait, Keller can travel without fear of recognition – no one knows he survived. Together, Allon and Keller begin the investigation, traveling through France to Nice, Aix-en-Provence, Rognes, Vaucluse and the Luberon, usually staying in “safe houses.”

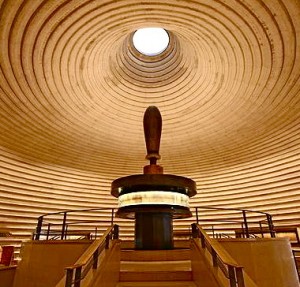

The Shrine of the Book, which houses the Dead Sea Scrolls. This building project was purportedly brought to fruition by Chiara Zolli, Gabriel Allon’s wife. Photo by Ron Peled

Throughout the first part of this book, the history of Gabriel Allon, his personal life, and his history as an assassin for the Israelis are revisited. (He personally murdered six of the Black September terrorists who had assassinated the Israeli athletes during the Munich Games.) Many of his past cases, developed in previous novels, are summarized briefly within the context of the developing action, in order to help readers remember the repeating characters, many of whom appear once again in this novel. Ari Shamron, former head of Israeli security, his successor Uzi Navot (Shamron’s second choice, since Gabriel Allon had refused the job), Gabriel’s wife Chiara, also an agent, and Eli Lavon, among others, all play a role here. The complexities of British politics are also examined, since Prime Minister Jonathan Lancaster is considered to be primarily the mouthpiece for the real ideas coming from his Chief of Staff, Jeremy Fallon. The dramatic conclusion to the first part, regarding the missing Madeline Hart, is followed by Allon’s deeper investigation into her background and the real reasons she was kidnapped.

In the second part, the novel becomes more complex and more relevant to present day international relations. When, during his investigations following the climax of the Madeline Hart search, Allon finds evidence that the Russians are interested in drilling for oil in the North Sea, he calls on Viktor Orlov for information on the Kremlin, the Russian oil business, and the involvement of Russian President Vladimir Putin. Orlov, once one of the richest oligarchs of the Russian oil industry, is now out of Russia and living in London. He and Gabriel Allon have a past history, and Orlov readily explains the maneuvering in Russia for control of the oil industry, the implications of which are obvious to the reader.

Though much of the excitement for which Silva is well known evolves as this novel further develops, the general subject matter itself is not as exciting as in some past novels. There is nothing here that compares in importance to the archaeological investigation of the Temple Mount on the site of the al-Aqsa Temple in Fallen Angel. Nor is there anything as historically significant as the study of the Vatican’s involvement in the Holocaust as in The Confessor. Nor the powerful interests involved in international art theft and smuggling, as in The Rembrandt Affair; nor the uncontrolled arms sales and the horrific implications for the future, as in Moscow Rules.

Viktor Orlov lives in a tall, narrow house on Cheyne Walk. London. This similar house on Cheyne Walk is where author George Eliot died in 1880.

This is not to say the book is not fun to read. It is, but it lacks the customary intensity and power of some of the earlier novels. The clear separation into two-parts prevents this nearly five hundred-page novel from developing tension in a cohesive, increasingly exciting narrative, and it leads to a narrative device that I do not remember seeing in previous Silva books: On several occasions during the conclusion, Silva ends up “telling about” what’s happening, instead of recreating the action and involving the reader in it. Some of the novel’s foreshadowing is provided by a Corsican fortune-teller, whom Gabriel not only visits but takes seriously, not a characteristic I would have expected from this assassin of a dozen or more men on behalf of Israeli security. Though there is a twist at the conclusion, which will please long-time readers, the novel ultimately left me feeling that the book lacked the drive and commitment of past novels. I read every word, but I was not engaged by it in a way which might have allowed me to “participate” in it as I have done with numerous other Silva novels from the past.

ALSO by Daniel Silva: THE FALLEN ANGEL, THE CONFESSOR, and THE HEIST

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears as part of an interview on http://www.today.com/

The Shrine of the Book, at the Israel Museum, purportedly brought to fruition by Chiara Zolli, wife of Gabiel Allon, contains the Dead Sea Scrolls. Photo by Ron Peled http://allaboutjerusalem.com/

The Ajaccio-Marseilles ferry is seen on http://thieery.photos.blog.free.fr

The Basilica of Sainte Anne in the Luberon is shown on http://www.bonjourquilts.com

The Cheyne Walk house of George Eliot, supposedly similar to the house belonging to Viktor Orlov, is from http://tonyshaw3.blogspot.com

ARC: Europa