“What kind of man would…consent to do a job that meant putting five or six thousand souls to death? I find it hard to give a student a bad grade at the end of the semester, let alone at the end of the year, but that is nothing compared to the way [SS guards]Götz and Meyer must have felt. Or what if they felt nothing at all?”

Th e speaker of this long monologue by Serbian author David Albahari is a teacher of Serbo-Croatian language and literature, a 50-year-old Jewish man who has been trying to fill in the spaces in his family tree after World War II in Yugoslavia. Of sixty-seven immediate relatives, only six have survived, all because they left Yugoslavia for other places—Argentina, Israel, America, Australia—or, like the speaker and his mother, escaped to rural areas where they could be hidden before the extermination of the Jews started. “I wanted to discover who I was and what I was, and where I had come from,” he says.

e speaker of this long monologue by Serbian author David Albahari is a teacher of Serbo-Croatian language and literature, a 50-year-old Jewish man who has been trying to fill in the spaces in his family tree after World War II in Yugoslavia. Of sixty-seven immediate relatives, only six have survived, all because they left Yugoslavia for other places—Argentina, Israel, America, Australia—or, like the speaker and his mother, escaped to rural areas where they could be hidden before the extermination of the Jews started. “I wanted to discover who I was and what I was, and where I had come from,” he says.

In Yugoslavia the extermination of Jews started early and was almost totally successful within a matter of months, with most of the Jewish men of Serbia shot to death by the fall of 1941, and “the Jewish Question in Serbia almost completely solved” by April, 1942, when virtually all Jewish men, women, and children were dead. Imagining the lives of Götz and Meyer, two SS guards who were responsible for over 5000 Jewish deaths, the speaker examines the events for which Götz and Meyer were responsible between November, 1941, and April, 1942—the executions of one thousand Jews per month in the Belgrade Saurer truck they drove daily. The truck, with its hermetically sealed rear compartment, had a hole in the floor into which the exhaust was pumped as prisoners were being taken from the Belgrade Fairgrounds camp, where they were housed, to “better” accommodations elsewhere, “a concern of the German government for the good of the prisoners” that the speaker finds “touching.”

Often juxtaposing atrocities against simple, folksy observation, the speaker fantasizes about “Götz, or was it Meyer,” a phrase which echoes throughout the narrative because of their interchangeability. As he puts himself into their minds, he wonders if they had nicknames, if their wives had pet names for them, and if they ever regretted what they were doing, since they were so good at their jobs. Particularly “successful” in their relationships with the prisoners who unloaded trucks and buried the corpses, they created an environment in which the prisoners could bury a truckload of dead bodies in less than an hour.

The speaker’s life, like the book itself, is “split in an orderly and painless fashion into three parallel lives.” His first “life” belongs only to him—getting up, shaving, reading the mail, watching television. His second life is “one of constant transformations”—in which he stares at the family tree and imagines himself as one of his vanished cousins or aunts or uncles. His third life “had two heads”—”I was…the angel of death and the driver, a soldier and a simple man, the pretend savior and the real executioner,” and he admits that there were moments when “I did not know who I was.”

Throughout the novel, as Albahari includes the terrible statistics, he also exhibits the ironies of the circumstances, setting the facts into sharp relief and increasing the shock. Gradually Götz and Meyer become more human (and even more horrifying because of it) for the reader, and when the speaker takes his class on a field trip to the site of the Fairgrounds camp, he asks them to imagine themselves as one of his relatives. One student remarks that she would not have gone to the camp if she had to leave her pets at home, deciding that this would have been “inhuman.” Another sees life at the Fairgrounds as “the greatest adventure of his lifetime.” As the horror of the events and the dissociation of the students from the magnitude of the crimes gradually sink in with the teacher, he comments that “Memory is the only way to conquer death, even when the body merely goes the way of all matter and spins in an endless circle of transformations.”

Throughout the novel, as Albahari includes the terrible statistics, he also exhibits the ironies of the circumstances, setting the facts into sharp relief and increasing the shock. Gradually Götz and Meyer become more human (and even more horrifying because of it) for the reader, and when the speaker takes his class on a field trip to the site of the Fairgrounds camp, he asks them to imagine themselves as one of his relatives. One student remarks that she would not have gone to the camp if she had to leave her pets at home, deciding that this would have been “inhuman.” Another sees life at the Fairgrounds as “the greatest adventure of his lifetime.” As the horror of the events and the dissociation of the students from the magnitude of the crimes gradually sink in with the teacher, he comments that “Memory is the only way to conquer death, even when the body merely goes the way of all matter and spins in an endless circle of transformations.”

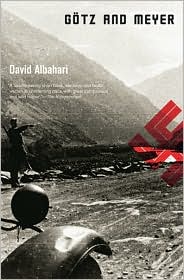

A strange novel of the Holocaust, all the more shocking because of the contrasts between the facts and the dark humor, Götz and Meyer is a memorable short novel and worthy addition to Holocaust literature.

Notes: The author’s photo appears on http://alchetron.com/David-Albahari-125664-W

The Synagogue of Novi Sad, Serbia, is from Wikipedia.