Note: This novel is WINNER of the Brazilian PEN Prize for Best Novel of 2011.

“In twenty or thirty years, no one in Brazil will talk about this [violent period] anymore. By the early twenty-first century not even historians will be interested…Bookstores will shelve works on the subject in the history section. In alphabetical order. Depending on author’s name, an account of torture in Brazil in the 1970s might be located between a volume about gold mining…and one on African influences in Brazilian folklore.”— The speaker, discussing the military dictatorship in Brazil, 1964-85.

Beginning his novel in Brazil during the military coup of 1964, and extending the story through to the twenty-first century, prize-winning Brazilian author Edgard Telles Ribeiro sets his novel, not in the streets, but in the country’s foreign service offices, a setting he knows well from his own experience. Telles Ribeiro was a journalist when the military coup of 1964 took place, and in 1967, he became a member of the Foreign Service, where he was able to observe the behavior he illustrates in this novel. Apparently modeling his main character on a real person, he tells his story through a first-person narrator, a story that he says has been so daunting that it has taken him forty years to come to grips with it. The need to write eventually overwhelmed him, he says, “not so much in order to reveal what we always knew within our group: namely, that the devil was in our midst…but out of my own need, as a witness to the adverse effects the period had on people I cared for.”

Beginning his novel in Brazil during the military coup of 1964, and extending the story through to the twenty-first century, prize-winning Brazilian author Edgard Telles Ribeiro sets his novel, not in the streets, but in the country’s foreign service offices, a setting he knows well from his own experience. Telles Ribeiro was a journalist when the military coup of 1964 took place, and in 1967, he became a member of the Foreign Service, where he was able to observe the behavior he illustrates in this novel. Apparently modeling his main character on a real person, he tells his story through a first-person narrator, a story that he says has been so daunting that it has taken him forty years to come to grips with it. The need to write eventually overwhelmed him, he says, “not so much in order to reveal what we always knew within our group: namely, that the devil was in our midst…but out of my own need, as a witness to the adverse effects the period had on people I cared for.”

The Brazilian foreign ministry in the 1960s and 1970s provided a most unusual, perhaps unique, atmosphere in which to work. Though the military ruled the country’s daily life and ran the security service, they themselves regarded the foreign ministry as “an elite group…[and] the generals tended to regard leftist leanings that might exist within it as more intellectual than radical in nature.” By the speaker’s own admission, this political contrast sometimes led to “bizarre situations: In a right-wing country, we were increasingly allowed to formulate a left-leaning foreign policy.” Eventually Brazil became the first country to recognize Angola’s socialist government and eventual independence, and to reestablish relations with Communist China, even as people within Brazil itself were disappearing and being executed by the military. If someone in the foreign service could keep his mouth shut about the disappearances, the torture, and the killing within the country, however, he could survive.

The Itamaraty Palace, where the Foreign Service has its offices, was designed by Oscar Niemeyer and built in Brasilia in 1967

The speaker’s former friend and colleague, Marcilio Andrade Xavier, known as Max, was a born survivor, the speaker tells us. Max was “one of the most pitiful symbols of our country at that time,” a confounding and wholly self-serving young man who managed to keep all options open and play all sides and interests for his own benefit, while carving out a place for himself in the maelstrom of Brazil. Max’s swift rise to high positions in the Foreign Service when he was still in his twenties, fascinated the speaker, in a cynical way, as he “readily adapted to the ever-changing conditions…swiftly scaling the ranks of our hierarchy over the twenty years of military rule, and then going on to achieve further triumphs after the return to political normalcy,” a complete about-face that Max,without any real ideology, made smoothly. Civil liberties might have been abolished, but Max knew how to play the game flawlessly.

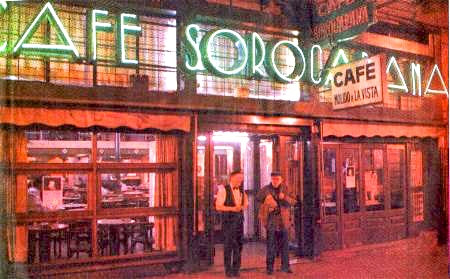

The Sorocabana in Montevideo, Uruguay, where Max enjoyed meeting contacts, is reputed to be to that city what Rick’s Cafe was to Casablanca.

After a long introduction about the period and about Max’s history, the speaker buckles down and gets into the real details of Max’s life. Already divorced when the action starts, Max soon marries an appropriate woman of wealth and social status and is sent from Brazil to Montevideo, Uruguay. There, the Brazilian ambassador is creating a network which will enable the Uruguayan military to consolidate their power as leaders of the country. The ambassador wants Max to help him quietly in Uruguay, and soon Max is ensconced as First Secretary in the office in Montevideo, making contact with the CIA and MI6. He watches as Uruguay becomes “the domino piece that, after Brazil and Argentina, would complete the shadow the military cast over the region, the one that would herald the next coup, this time in Chile.” When the inevitable coup begins, Max is sent to Santiago to work behind the scenes. Through all the coups and their later countercoups in nations throughout South America over the next twenty years, Max plays all sides and stays afloat, though it takes a toll on his personal relationships.

The narrator spends long years apart from Max, working around the world, from Vienna and Peru to Los Angeles, leading a different kind of life and providing a contrast to Max. By the time twenty years have passed, and the governments of these countries have changed, the speaker finally learns from his own international connections, just how Max managed to survive. The contrasts between the two illustrate the complexity of their foreign service assignments and the manner in which each person’s own personality colors and sometimes controls not only his own actions but those which have been taken on behalf their countries.

Though many other writers have written novels about various coups in South America, this story is unusual, perhaps unique, in that its focus is squarely on the foreign service and the role of its representatives. Not a single scene here reflects the tortures, the murders, or the disappearances which are so traumatizing, and none of the major military leaders responsible for these actions are featured here. This approach works well for people in Brazil, Uruguay, Chile (and eventually Argentina), who are well familiar with the events which have often dramatically affected their own lives, though much of the action in this book will be new to many American readers. The movement back and forth in time over the eventual course of over forty years and several countries is sometimes challenging, and the mysterious Max, a lone wolf, is not someone with whom the reader will identify. The narrator’s own reports contain more thoughtful analysis than direct action. Still, the author ultimately raises important philosophical questions: “In the space of a generation, thousands of people…had been imprisoned, tortured, and killed in the name of priorities long since forgotten. Who would answer…[who] would face a camera to publicly lament what had happened, as Robert McNamara had with respect to the horrors caused by the Vietnam War? What had occurred four decades earlier…remained suspended in time…on a planet deprived of memory.” The author hopes to correct that.

Photos, in order: The author’s photo is from http://www.librosdelasteroide.com

The Itamaraty Palace, built in Brasilia for the Foreign Service in 1967, was designed by Oscar Niemeyer. http://www.architravel.com/

The Sorocabana in Montevideo, Uruguay, where Max enjoyed meeting contacts, is reputed to be to that city what Rick’s Cafe was to Casablanca. http://cafe-sorocabana.blogspot.com/

The Chilean army attacked La Moneda, the Presidential Palace in Chile, in 1973. President Salvador Allende died in the attack, reportedly by his own hand. http://www.theguardian.com/

The Presidential Palace in Brasilia, also designed by Oscar Niemeyer, was built in 1957-58. http://www.thewhig.com/

ARC: OTHER PRESS