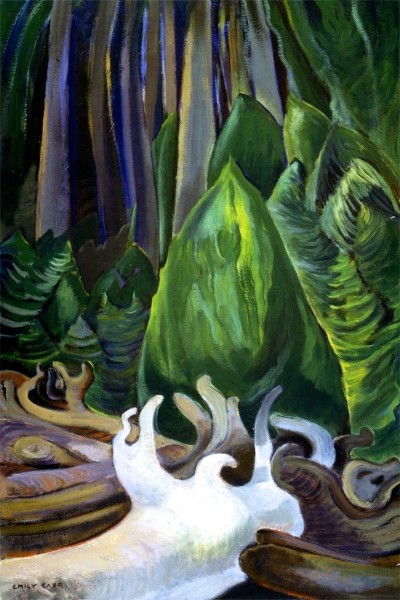

“Over the past few decades, Emily Carr’s reputation has soared so high that it now can be argued she is Canada’s best-known artist, historic or contemporary. Her impassioned paintings of the West Coast of Canada – her depiction of the monumental sculpture of British Columbia’s indigenous peoples and of the towering trees and dense undergrowth of the region’s rain forests, executed during the early decades of the twentieth century – have superseded [every other] claim to Canadian wilderness. And to national identity.” – Robin Laurence, “The Making of an Artist,” Introduction, 2005.

In this autobiography famed Canadian painter Emily Carr also shows her superb talent as a writer and observer, concentrating on her feelings and her intense responses to life’s challenges over the seventy-four years of her life. Hospitalized with heart problems in 1945, the year she died, she used her last days to review the many journals she kept throughout her life and to select and describe what was most important to her for this book. She does not worry about dates here – they were not as important to her as the events themselves – and, as a result, the reader is drawn into her life and allowed to share it with her in ways that she denied to others during her lifetime. She had few friends, and those readers unfamiliar with her background will be surprised to see that she dedicates this autobiography to Lawren Harris, one of the founders of the Group of Seven, and one of Canada’s most famous landscape painters, whose work became known for its increasingly abstract style. He is the man whose actions saved Emily Carr’s life as a painter.

In this autobiography famed Canadian painter Emily Carr also shows her superb talent as a writer and observer, concentrating on her feelings and her intense responses to life’s challenges over the seventy-four years of her life. Hospitalized with heart problems in 1945, the year she died, she used her last days to review the many journals she kept throughout her life and to select and describe what was most important to her for this book. She does not worry about dates here – they were not as important to her as the events themselves – and, as a result, the reader is drawn into her life and allowed to share it with her in ways that she denied to others during her lifetime. She had few friends, and those readers unfamiliar with her background will be surprised to see that she dedicates this autobiography to Lawren Harris, one of the founders of the Group of Seven, and one of Canada’s most famous landscape painters, whose work became known for its increasingly abstract style. He is the man whose actions saved Emily Carr’s life as a painter.

Emily Carr begins Growing Pains by describing her early childhood as the eighth of nine children of a Presbyterian minister in Victoria, Vancouver Island, Canada. Born in 1871 and brought up to a relatively comfortable life, Carr was orphaned before she left her teens and faced her future being ruled by her oldest sister, her guardian. (Here, as in a few other places, the book’s chronology is unreliable. Carr indicates that she was a young child when she was orphaned, but the dates in Wikipedia indicate that her mother died when she was fifteen and that her father died two years later.) At one point before she was twenty, Carr visited an aboriginal settlement on the west coast of Vancouver, a trip which was the turning point in her life. She spent the weeks of her trip sketching the totems, the village life, and the people, and would do so again, more seriously – after she had acquired the art skills she needed to bring these people fully to life. To acquire these skills, she persuaded her guardian sister to let her attend the San Francisco Art Institute, where she participated in traditional art programs for two years but made few friends.

Time and Emily Carr’s activities get compressed here, as Carr moves along stressing the events which were most important to her while still ignoring dates. It was apparently 1899 when Carr, by now in her late twenties, went to London to study at the Westminster School of Art, a time in which she made some progress but found the British her total opposites in terms of sharing feelings and ideas. While there, she was courted by a young man whom she was unable to discourage, though she knew she would not marry and told him so. Unsatisfied with her art progress, she began to take night classes elsewhere in London to learn what she felt she needed to learn. It was during this difficult time that a doctor intervened to tell her she needed total rest, and admitted her to a sanatorium. She spent the entire time in bed, and did not leave the facility for eighteen months, a stay which she does not explain in further detail.

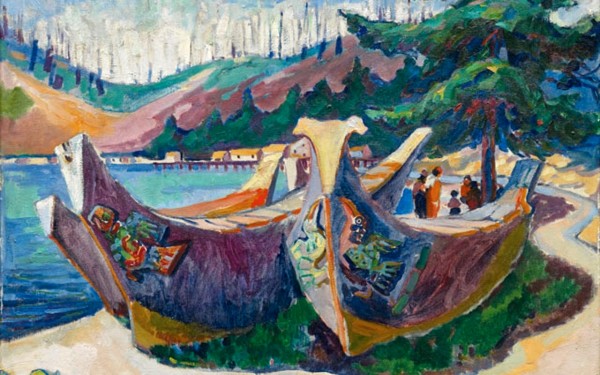

Returning home to Canada after more than five years abroad, Carr found Vancouver a lonely place without any art life, except for the elite Ladies Art Club. She tried teaching art in a school for a while, then returned to her interests in the aboriginal villages nearby and even on into Alaska, which she visited with a sister. These resulted in a series of paintings, in which her own “seeing” loosened the tightness she had learned in her English art studies. Another trip to Europe and further study in Paris led her to become interested in the work of the post-Impressionists, but upon her return to Canada, she found no interest when she introduced her new color palette in her own show. In the summer of 1912, she returned to painting the aboriginal people of Haida Gwaii, finally achieving some recognition when she showed this work, but still not enough to support her. Discouraged and depressed, she gave up, stopped painting entirely for fifteen years, and ran an apartment house. When, unexpectedly, a representative of the Canadian National Gallery suddenly wrote to see if he could show fifty of her aboriginal paintings from fifteen years ago, she happily agreed, this unexpected contact leading to her invitation to a major show in Ottawa, national praise for her work, and her fortuitous meeting with Lauren Harris.

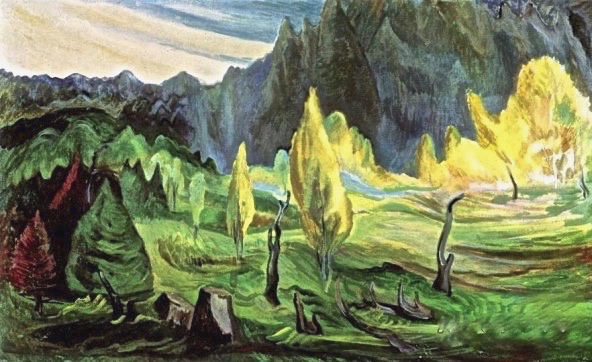

“Sea Drift,” 1931, showing the influence of the Group of Seven with its semi-abstract and lush plant life.

Based in Toronto, Lawren Harris met Emily Carr when she was already in her late fifties. She had stopped in Toronto on her way back to Vancouver after the successful Ottawa show, and had sought out Harris and the other Group of Seven painters because they were doing landscapes which she found stunning. It was this brief contact, and Harris’s continuing interest in her work, conveyed through their correspondence, which kept her motivated and working in the Canadian far west when she became discouraged. Harris’s thoughtful, personal commentary, which Carr acknowledges and praises in this autobiography, helped keep her motivated forever afterward, until her health required her reluctant retirement from painting, about ten years later. Her cardiac problems, for which she had been hospitalized for a year, finally claimed her life in 1945, at age seventy-four.

Readers of Growing Pains, her intimate journal, will empathize with Emily Carr – ahead of her time and out of sync with her environment, no matter where she was. Forging ahead on her own, while also trying to support herself, she tried to be true to herself and her art in an effort to pursue her long-term goals, even if that meant giving up her painting. Spurning ordinary social contacts, since there were few, if any, artists then who shared her interests on Vancouver Island, Emily Carr was a loner whose saving grace, ultimately, was her connection to Lawren Harris, whose attention and respect made her an honorary member of the Group of Seven. A fascinating and intense autobiography by a woman who desperately wanted to achieve success in her work and nearly missed her chance.

Photos: The author’s photo appears on https://www.pinterest.com/

“Indian Village, Alert Bay,” 1912 is found on http://www.museevirtuel.ca/

“War Canoes, Alert Bay”, 1912: https://arthistoryproject.com

“Sea Drift,” 1931: https://www.pinterest.com/

“Indian Church”: https://en.wikipedia.org/

“The Clearing”: http://www.museevirtuel.ca