“For as long as Tancredo can remember, [the night of Fr. Matamoros’s Mass] was the night that shed light on all of his nights, a different and devastating night, the beginning or the end of his life, agony or resurrection, God alone knows which.”

The acolyte Tancredo, the tormented main character of this wicked satire by Colombian author Evelio Rosero, has a terrible fear of becoming an animal, especially on Thursdays. A young hunchback from Bogota, Tancredo has been living in the rectory of a Bogota church since childhood, when he was taken in by Fr. Juan Pablo Almida and given an education with the idea that he would one day enter the church. The biggest problem for Tancredo, however, is that Fr. Almida works him so hard he has little time for study, especially since he has been assigned the task of running the church’s Community Meals outreach program, Monday through Friday. Each day serves a different congregation – prostitutes on Mondays, the blind on Tuesdays, street kids on Wednesdays, and families with children on Fridays. Thursdays, however, are “a living hell,” the day that “crowds of old people start pouring in from the four corners of the city, Bogota spitting them out by the dozen.”

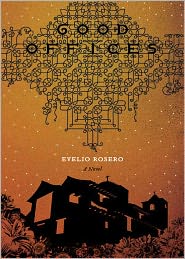

The acolyte Tancredo, the tormented main character of this wicked satire by Colombian author Evelio Rosero, has a terrible fear of becoming an animal, especially on Thursdays. A young hunchback from Bogota, Tancredo has been living in the rectory of a Bogota church since childhood, when he was taken in by Fr. Juan Pablo Almida and given an education with the idea that he would one day enter the church. The biggest problem for Tancredo, however, is that Fr. Almida works him so hard he has little time for study, especially since he has been assigned the task of running the church’s Community Meals outreach program, Monday through Friday. Each day serves a different congregation – prostitutes on Mondays, the blind on Tuesdays, street kids on Wednesdays, and families with children on Fridays. Thursdays, however, are “a living hell,” the day that “crowds of old people start pouring in from the four corners of the city, Bogota spitting them out by the dozen.”

Ignoring all the “rules,” the elderly “act as though they were respected clients and he, the maitre d’, their waiter.” They are impatient and rude, and some of them are clearly mad. Worst of all, eleven of them have died in the hall or waiting in line during the three years of the program, and Tancredo has often had to wait with their bodies for hours in the same hall where the meals are served, since those in authority are in no hurry to arrive. “It is your cross to bear,” Fr. Almida tells Tancredo,” and also your redemption. Resign yourself.”

The Lilias, a group of three widows whose menfolk have all been assassinated in a raid on their rural village, are also church residents – they cook for the church – and they, too, are tired, never having a day off, cooking huge meals for the hundred or more poor each day, with no extra help, and then preparing all the food for other church functions. Sabina Cruz, a young woman so fair she is almost albino, is the young goddaughter of the sacristan, the pompous Celeste Machado, and, residing at the church, she acts as its secretary. Machado, “mute, dark, and stony,” is surrounded by a “ring of blackness like a pit,” and when he and Fr. Almida start prying into the food program, Tancredo can only wonder about their “obscure purpose” in calling him in to make a report. They want numbers with which they can impress their wealthy benefactor, Don Justiniano, whose every visit until now has meant a case full of money for the church. Recently, however, Fr. Almida has started to worry that “lies” by other (jealous) priests about him and his church may swindle them out of their funding, and he and Machado decide to visit Don Justiniano to plead their case. For the first time in forty years, a substitute will have to perform the Sunday services.

The arrival of Fr. San Jose Matamoros del Palacio and the departure of Fr. Almida and his sacristan for their meeting with Don Justiniano set the stage for the novella’s turning point, both hilarious and horror-filled. Fr. Matamoros is very different from Almida and Machado, singing the Mass and inspiring the congregation with his passion. Passersby, lured by the music to enter the church for the service, some for the first time, agree with the ladies of the Neighborhood Civic Association that the service was so “lovely” that “For a moment we thought it wasn’t an earthly one. The Reverend who celebrated it must be…a special person.” When Fr. Matamoros concludes the service, the Lilias persuade him to stay the night in the presbytery, and when all the electricity goes out, those who have worked much of their lives in and for the church make their confessions, suggesting indirectly some of the sins of Fr. Almida and Celeste Machado.

The arrival of Fr. San Jose Matamoros del Palacio and the departure of Fr. Almida and his sacristan for their meeting with Don Justiniano set the stage for the novella’s turning point, both hilarious and horror-filled. Fr. Matamoros is very different from Almida and Machado, singing the Mass and inspiring the congregation with his passion. Passersby, lured by the music to enter the church for the service, some for the first time, agree with the ladies of the Neighborhood Civic Association that the service was so “lovely” that “For a moment we thought it wasn’t an earthly one. The Reverend who celebrated it must be…a special person.” When Fr. Matamoros concludes the service, the Lilias persuade him to stay the night in the presbytery, and when all the electricity goes out, those who have worked much of their lives in and for the church make their confessions, suggesting indirectly some of the sins of Fr. Almida and Celeste Machado.

From the powerfully descriptive (and darkly comic) opening pages, in which Tancredo must handle the problems of his elderly patrons at the Thursday Community Meals, to the later pages in which the full effects of Fr. Matamoros’s Mass are shown in the lives of the servants of the church, Rosero creates dramatic moods and atmosphere, showing the hypocrisies of every person in the novel. His dark satire is not leveled at the church itself so much as it is at the fallible human beings who represent it, the harshest satire leveled at those in positions of power who mock the vows they have made by abusing the trust of the people who work for them and believe in them. The pacing is perfect. Even when describing the action behind the scenes in the church “household,” he keeps his story moving, filling it with mysteries, ironies, and hints of wrongdoing. His imagery of darkness, from his description of Machado to the power failure after the Mass and his later description of the Lilias’ black shawls is consistent and thematically revealing.

From the powerfully descriptive (and darkly comic) opening pages, in which Tancredo must handle the problems of his elderly patrons at the Thursday Community Meals, to the later pages in which the full effects of Fr. Matamoros’s Mass are shown in the lives of the servants of the church, Rosero creates dramatic moods and atmosphere, showing the hypocrisies of every person in the novel. His dark satire is not leveled at the church itself so much as it is at the fallible human beings who represent it, the harshest satire leveled at those in positions of power who mock the vows they have made by abusing the trust of the people who work for them and believe in them. The pacing is perfect. Even when describing the action behind the scenes in the church “household,” he keeps his story moving, filling it with mysteries, ironies, and hints of wrongdoing. His imagery of darkness, from his description of Machado to the power failure after the Mass and his later description of the Lilias’ black shawls is consistent and thematically revealing.

Even Rosero’s use of names adds to the satire and its message. Translated, Tancredo means “well considered counsel or advice,” something the acolyte has tried hard to provide, despite the roadblocks put in his way. The venal Almida’s name is appropriate, too – “ambitious” – and Celeste Machado, the sacristan, translates (tellingly) to “heavenly hatchet.” The Lilias (“lilies”) and Sabina Cruz (whose name refers to the Sabine women kidnapped as “wives” of the citizens of Rome) need little explanation. Most significantly, Fr. Matamoros’s name means “Moor killer,” or “killer of darkness.” The wonderful ironies and surprising plot twists, as Rosero takes the reader on a whirlwind of imagery and emotion, make this novella as memorable as any satire I’ve read in ages, and the extent to which he trusts the reader to fill in the blanks at the end make it great fun, a first rate satire which examines sin and possible “redemption,” and, as Tancredo says, “agony or resurrection.”

Also by Evelio Rosero: THE ARMIES

Photos, in order: The author’s photo is by Juan Gabriel Vasques, in El Pais, Dec. 23, 2009, appears here: http://picasaweb.google.com

The old church in Bogota is by http://kheussler.de

The interior of a Bogota church appears on http://www.123rf.com

One of the motifs of the book is a poem/song by St. Teresa of Avila, entitled “Let Nothing Disturb Thee, Nothing Afright Thee, All things are passing. God never changeth, Patient endurance attaineth to all things.” Here is it set to music, perhaps to the same tune used by Fr. Matamoros more than once. (The Spanish version, here, is “Nada Te Turbe.”)