Note: Aravind Adiga’s debut novel, The White Tiger, was WINNER of the Man Booker Prize in 2008.

“Pigeon, crow, hummingbird; spider, scorpion, silverfish, termite and red ant; bats, bees, stinging wasps, clouds of anopheles mosquitoes. Come, all of you: and protect me from human beings.” –Yogesh A. Murthy, “Masterji”

With a breezy, irreverent point of view and a fine eye for the kinds of details which make characters and scenes memorable, Aravind Adiga tells an often humorous morality tale about life in an area of Mumbai undergoing residential redevelopment. And just as his Booker Prize winning novel, The White Tiger, was celebrated because “it shocked and entertained in equal measure,” this novel, too, both shocks and entertains. Once again, Adiga explores the theme of moral compromise, which India seems to require of its citizens if they are to become financially “successful.” The extreme poverty and the masses of other enterprising residents with whom everyone except the very rich must compete make absolute morality virtually impossible, Adiga seems to suggest, a luxury which few can afford, and Adiga draws from these conflicts in his novels. In The White Tiger, the main character is a young entrepreneur aiming for success; here, the main characters are a group of residents in a decaying apartment house, many of them friends for many years, who are suddenly faced with the previously undreamed of possibility of great wealth.

With a breezy, irreverent point of view and a fine eye for the kinds of details which make characters and scenes memorable, Aravind Adiga tells an often humorous morality tale about life in an area of Mumbai undergoing residential redevelopment. And just as his Booker Prize winning novel, The White Tiger, was celebrated because “it shocked and entertained in equal measure,” this novel, too, both shocks and entertains. Once again, Adiga explores the theme of moral compromise, which India seems to require of its citizens if they are to become financially “successful.” The extreme poverty and the masses of other enterprising residents with whom everyone except the very rich must compete make absolute morality virtually impossible, Adiga seems to suggest, a luxury which few can afford, and Adiga draws from these conflicts in his novels. In The White Tiger, the main character is a young entrepreneur aiming for success; here, the main characters are a group of residents in a decaying apartment house, many of them friends for many years, who are suddenly faced with the previously undreamed of possibility of great wealth.

The fifteen apartments of Vishram Society Tower A in Vakola, “the toenail of Santa Cruz,” near Mumbai’s airport, are home to a group of relatively middle-class residents – a social worker, a hardware specialist, a retired accountant, a teacher, and a journalist, for example. All of them “pay taxes, support charities, and vote in local and general elections,” but since the average Indian citizen earns the equivalent of $800 a year (in 2008 – 2009), they have little extra  money to maintain their building and its infrastructure. Residents never know when they will have hot water, and the electricity is sometimes unreliable. “After four decades of monsoons, erosion, wind-weathering, air pollution, and the gentle but continual vibrations caused by the low-flying planes, Tower A stands in reasonable chance of complete collapse in the next monsoon.”

money to maintain their building and its infrastructure. Residents never know when they will have hot water, and the electricity is sometimes unreliable. “After four decades of monsoons, erosion, wind-weathering, air pollution, and the gentle but continual vibrations caused by the low-flying planes, Tower A stands in reasonable chance of complete collapse in the next monsoon.”

When Darmen Shah, who works for the Confidence Group, makes an offer to buy out the residents to build a super-luxury apartment building, most of them are ecstatic. He is offering a windfall of the equivalent of $330,000 per apartment if they will vacate so he can raze their building and build his new development. The only catch is that all of the residents must agree to sell.

At first, there are a few who resist—Mrs. Rego, a social worker and communist; the Pintos, an elderly couple in which the wife is blind and fears that she will not be able to negotiate a new building and the space around it if she moves; and “Masterji,” Yogesh A. Murthy, a former school teacher whose wife has died less than a year ago and who has special memories of Tower A.

Versova Beach

Obviously, the pressure will soon be raised to excruciating levels as the anxious residents try to persuade the holdouts to allow the whole group to collect previously unimaginable wealth from the sale of their property. An equal, if not greater pressure, is exerted by the developers, who must have this property to reach their goals. The biggest difference is that the developers are not new to this situation and have more experience in “persuasion” than do the residents. As everyone eventually focuses on Masterji, who is the last holdout, they must justify their behavior, at least to themselves, when they abandon the past and their long personal relationships to ensure the promise of life-long wealth. The reader, of course, is constantly aware that the people working for the development company are “Confidence” men.

As the actions to sway Masterji reach dangerous levels, the author explores just how fragile friendship can be and how far people will go for guaranteed wealth. Unfortunately for the reader, the pressure on Masterji is not unexpected or unique, and I suspect that though most readers will be impressed by the ethical stand taken by Masterji, they will also feel that this is unrealistic and, eventually, silly, in the face of the possibilities open to everyone if they accept the offer. The conclusion has some surprises, and the Epilogue brings the conclusion up to date.

Adiga, an accomplished writer of description, imbues his descriptions with the kind of details and images that make the apartment house and its large cast of characters memorable. A door in the apartment house has “an eczema of blue-skinned gods” on a door; the floor of the apartment behind it is “an archipelago of newspaper and undergarments.” The residents at the beginning of the novel, each of them jealous of something another may have, realize that “a chain of envy links them, showing each what was lacking in life, but offering also the consolation that happiness was next door.” The women carrying troughs of wet cement up to the upper floors of construction sites; Mary, the housecleaner who lives in the slums but has higher goals for her son; and Ramu, the mute Down Syndrome son of the Puris, all minor characters, become memorable through their detail.

Ganesha Shrine

The novel, however much fun it may be, especially for those who have not read Adiga before, lacks the kind of powerful thematic development that The White Tiger has. It is a morality tale, and the downward spiral, as everyone focuses on persuading Masterji to give in, by whatever means necessary, conjures up the kinds of nastiness which one regularly sees in other kinds of bullying. It is the extent to which these seemingly average people will go that makes this novel different and, eventually, memorable.

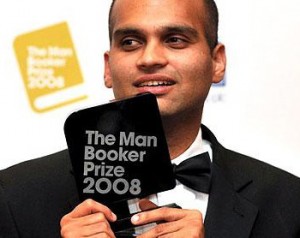

Photos, in order: The author’s photo is from his Booker Prize ceremony, 2008: http://www.telegraph.co.uk

Versova Beach, where Mr. Shah meets with his “left hand man,” Shanmugham, in the morning, is seen on the blog of Akshay Mahajan, a site with spectacular photographs: http://trivialmatters.blogspot.com

The bronze statue of Nataraja, which sits in Mr. Shah’s living room, is from http://www.bronzecreative.com/

The Ganesha Shrine (to the “elephant god”) at the Siddhivinayak Temple, where Damen Shah’s son prays that Shah will fail, is featured on http://www.facebook.com

Note: Also by Adiga: THE WHITE TIGER and AMNESTY