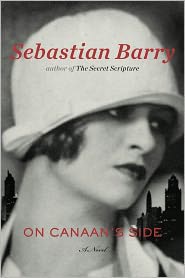

Note: Both of Barry’s previous two novels, A Long, Long Way (2005) and The Secret Scripture (2008) were on the Shortlist for the Man Booker Prize. The latter was WINNER of the James Tait Black Memorial Prize and the Costa Award.

Grief: “The feeling of it is like a landscape engulfed in floodwater in the pitch darkness, and everything, hearth and byre, animal and human, terrified and threatened. It is as if someone, some great agency, some CIA of the heavens, knew well the little mechanism that I am, and how it is wrapped and fixed, and has the booklet or manual to undo me, and cog by cog and wire by wire is doing so, with no intention ever to put me back together again…”

On the opening page of this emotionally overwhelming novel, Lilly Bere, age eighty-nine, begins the grand story of her seemingly insignificant life, a story in which she speaks directly from her heart, begging to know “How can I get along without Bill?” her grandson who has just died following the First Gulf War in Kuwait (1990 – 1991). Each of the next sixteen chapters is one more numbered day “without Bill,” and we soon learn through flashbacks that Lilly and her family have suffered deaths connected to three earlier wars – the Great War (1914 – 1918), the Irish War for Independence (1919 – 1921), and Vietnam (ca.1965 – 1975). Though all the men she loved did not necessarily die in combat, their deaths were all inescapably war related, and Lilly becomes, in many ways, the prototypically devastated wife of Tadg Bere (in the Irish Revolution), sister of Willie Dunne (the Great War recruit previously featured in The Secret Scripture), mother of Ed (in Vietnam), and grandmother of Bill (in Kuwait). As their mourner, she is equally a victim of the wars that have taken her men.

On the opening page of this emotionally overwhelming novel, Lilly Bere, age eighty-nine, begins the grand story of her seemingly insignificant life, a story in which she speaks directly from her heart, begging to know “How can I get along without Bill?” her grandson who has just died following the First Gulf War in Kuwait (1990 – 1991). Each of the next sixteen chapters is one more numbered day “without Bill,” and we soon learn through flashbacks that Lilly and her family have suffered deaths connected to three earlier wars – the Great War (1914 – 1918), the Irish War for Independence (1919 – 1921), and Vietnam (ca.1965 – 1975). Though all the men she loved did not necessarily die in combat, their deaths were all inescapably war related, and Lilly becomes, in many ways, the prototypically devastated wife of Tadg Bere (in the Irish Revolution), sister of Willie Dunne (the Great War recruit previously featured in The Secret Scripture), mother of Ed (in Vietnam), and grandmother of Bill (in Kuwait). As their mourner, she is equally a victim of the wars that have taken her men.

Though she symbolizes the effects of war on women and children, as much as on the soldiers who fight, Lilly’s reaction to the deaths in her family is so personal and so heartfelt that she makes each death a new heartbreak for the reader, each individual death unique and affecting. “Greece, America, Arabia, Ireland. Home places,” she thinks. “Nowhere on earth is not a home place. The calf returns to where it got the milk. Nowhere is a foreign place. It is home for someone, and therefore us all.”

Lilly, born around 1903, in Wicklow, Ireland, was forced to escape to America in 1920, with the love of her life, to avoid a contract placed on him for choosing the wrong side in the Irish War for Independence. Settling in Cleveland, she had thought, upon first arriving in America, that she had reached the land of Canaan, the Promised Land of the Bible to which Moses led the Israelites out of Egypt and across the Red Sea, but she soon discovers that Canaan is always just out of reach for her. She tries, as the tells her sad story, however, to “dwell on the things I love, even if a measure of tragedy is stitched into everything.” Because Lilly feels far more deeply than she thinks, she succeeds in involving the reader completely as she tells her story, and it is to author Sebastian Barry’s immense credit that he is able create this identification on the level of feelings without resorting to any kind of easy sentimentality or maudlin imagery.

The author began his career as a poet, and it shows here. His lively and unforgettable scenes are filled with perfect, vivid details, his images and descriptions enhanced by the hypnotic rhythms and the cadences of poetry. Refrains and repeating symbols (Canaan, a dancing bear, Homer’s Odyssey, the wayward calf), which are more often associated with poetry or music than with a biography, keep the reader’s eye on the universal even while succumbing to the power of the moment.

The book ultimately succeeded in reducing me to tears, not just from the overwhelming sadness of some parts of the story but because of the overwhelming beauty and control of Barry’s language. In one remarkable passage in a Cleveland fun park, for example, he creates one of the most beautiful sentences ever – a nearly five-hundred-word single sentence which recreates the movement and speed of the rollercoaster on which Lilly rides, while simultaneously revealing her feelings for the two other people who accompany her. Even Barry’s “ordinary,” much shorter descriptions are just as memorable: Lilly’s husband Joe “in his civvies…was all spark and tornado”; at one point Lilly’s heart “lifted like a pheasant from scrub…its wings utterly opened in fright and exulting.” Lilly’s own attitude toward her life is that “My years have no width or length, have no dimension at all, just the downturn of a bird’s wings. So quick.”

Barry’s “ordinary,” much shorter descriptions are just as memorable: Lilly’s husband Joe “in his civvies…was all spark and tornado”; at one point Lilly’s heart “lifted like a pheasant from scrub…its wings utterly opened in fright and exulting.” Lilly’s own attitude toward her life is that “My years have no width or length, have no dimension at all, just the downturn of a bird’s wings. So quick.”

I have deliberately avoided a plot summary here to avoid spoiling the personal nature of Lilly’s involvement, along with those she loved, in life-changing world events. Ignoring any semblance of a linear narrative, Lilly provides free-form reminiscences about her escape to the United States after the Irish Revolution, along with a wide variety of world events. Because of the nature of the reminiscences, Lilly sometimes refers to characters she has not previously identified, but Barry’s imagery is so sharp that these people come alive memorably when they are reintroduced and placed into context later in the novel.

Barry’s scope is enormous, despite the very personal focus on Lilly, who tells us, among other things, that her friend Mr. Dillinger’s mother and sister died in Dachau. Her best friend, Cassie Blake, with whom she worked, has suffered life-long prejudice for her race, and the death of Martin Luther King is a reference point here. The death of a U. S. senator, shortly thereafter, provides another reference point. The abuse of servants, especially blacks like Cassie, often considered to be mere property, is matched by moments of great kindness by Mrs. Wolohan, who provides a home for Lilly. The huge East Ohio Gas Company Explosion of 1944, which killed one hundred thirty people, is a major turning point, and at another point, the elegance of the Hamptons contrasts directly with the lure of Las Vegas.

Barry’s scope is enormous, despite the very personal focus on Lilly, who tells us, among other things, that her friend Mr. Dillinger’s mother and sister died in Dachau. Her best friend, Cassie Blake, with whom she worked, has suffered life-long prejudice for her race, and the death of Martin Luther King is a reference point here. The death of a U. S. senator, shortly thereafter, provides another reference point. The abuse of servants, especially blacks like Cassie, often considered to be mere property, is matched by moments of great kindness by Mrs. Wolohan, who provides a home for Lilly. The huge East Ohio Gas Company Explosion of 1944, which killed one hundred thirty people, is a major turning point, and at another point, the elegance of the Hamptons contrasts directly with the lure of Las Vegas.

As the eighty-nine-year-old Lilly contemplates her own imminent death and tries to imagine whether anyone, anywhere, will ever want her little collection of saved treasures, mementoes of those she has loved, she feels a small sense of victory, whether or not she ever reaches Canaan: “I stood [in my little house], an utterly old, ruined, finished woman.…The darkness was so dark that it looked to me like light, though it wasn’t, it was a dark I understood well enough, it was the insides of something, like pips, like kernels, hard poems and items of God that God keeps his own counsel on, keeps secret and marvelous, almost selfishly, greedily, but who can blame Him?” Few who meet Lilly will be able to forget her – she works her way inside us and sees, and thinks, and feels, and ultimately reminds us of who we really are and where, if anywhere, we fit in life’s grand scheme.

ALSO by Barry: DAYS WITHOUT END and A THOUSAND MOONS

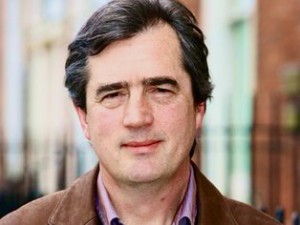

Photos, in order: The author’s photo is from http://www.rte.ie/

The marine equipment in Kuwait is seen on http://kitroane.com

The headline from the Cleveland newspaper and the image of the fire and explosion at the East Ohio Gas Tank (1944) appear on http://csudigitalhumanities.org

The Mercedes Benz Polo Challenge, hosted by the Bridgehampton Polo Club at Two Trees Farm, is a major event in the community where Lilly worked for the wealthy Mrs. Wolohan. http://www.primelocationblog.com