“Even when you think you know what the law says, some smart-arse in a wig finds a new wrinkle in an old rule and you watch some sniggering thug waltz out of court. When the Law is a bouncing ball on a spinning wheel, all that a righteous man can aim for is order.”

Bringing ord er to Dublin is Garda Detective Inspector Harry Synnott’s specialty. A man married for fifteen years and divorced for six, he is too busy to spend much time with his teenaged son. His whole life is wrapped up in trying to see that order prevails—either order recognized as justice by the courts or the order that Harry and his Garda officer pals bring about themselves, when their evidence of a felon’s guilt does not meet court standards.

er to Dublin is Garda Detective Inspector Harry Synnott’s specialty. A man married for fifteen years and divorced for six, he is too busy to spend much time with his teenaged son. His whole life is wrapped up in trying to see that order prevails—either order recognized as justice by the courts or the order that Harry and his Garda officer pals bring about themselves, when their evidence of a felon’s guilt does not meet court standards.

Despite his willingness to ignore the niceties of law, Harry Synnott has a conscience, however, and he is shunned by many of his fellow Gardai because he testified against his fellow officers in the brutal beating of a prisoner. “It wasn’t the prisoner’s welfare that mattered to Harry Synnott. What was working away inside his gut was the blatant use of violence…the assumption that membership of the force automatically tied him into that shameless wielding of unbounded power.”

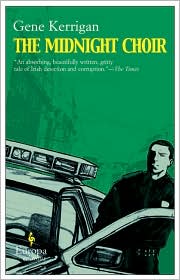

In clear prose which often contains bits of black humor and a great deal of irony, Irish author Gene Kerrigan sets the primary story in Dublin, and the secondary, companion story in Galway, until they overlap. New information discovered during the Galway case brings about a devastating conclusion which shakes Harry to the depths of his soul.

The Galway story seems simple enough: Garda Joe Mills and Garda Declan Dockery go to the roof of a pub where a man is threatening suicide. They save him from suicide only to discover that the man’s clothes are covered in blood. He will not tell his name, later discovered to be Wayne Kemp, and the only statement he makes is an enigmatic, “I’d never hurt a woman before.” Kemp’s only connections with Dublin are that he once worked for a Dublin security firm, and that his sister is a Dublin resident, and Kemp is so disturbed that he can provide no useful information for the Galway Gardai.

Garda station, Dublin

In Dublin, Harry Synnott is treading the minefield of police politics, moving from station house to station house, until he is finally recommended for a job with Europol, to start when his current case load is finished. As the novel moves from a Wednesday to the following Tuesday, the inexorable unfolding of events in several of Synnott’s cases leads to a crisis and grand climax, both in terms of the action and in terms of Synnott’s character. Synnott and Det. Garda Rose Cheney are investigating allegations of rape and abuse brought by Teresa Hunt against Max Hapgood, the son of a wealthy businessman with top-notch lawyers and public relations people. As he contemplates the fact that “justice” for the wealthy is far different from that of the poor, Synnott is also trying to get help for Dixie Peyton, a poor junkie, sometimes an informer, who has robbed a tourist couple with a syringe as a weapon. A businessman with an indeterminate business, having spent weeks monitoring activity at a jewelry shop, commits a robbery and a man dies, and the Irish mob enters the picture, too. As the details of these cases unfold during the space of one week, one of Synnott’s old cases, the “Swanson Avenue” case, casts its long shadow and eventually raises serious questions about justice, responsibility, and guilt.

The charming streets of Galway

In this intriguing police procedural, Kerrigan keeps the action crisp and fast-paced, with plenty of complications to keep the reader busy. What makes this novel different from so many of this genre is that he is also outstanding at creating characters with whom the reader develops empathy—Synnott, Dixie Peyton and her son, and eventually Det. Rose Cheney. Synnott, himself, is likeable and basically good-hearted, but he is busy, and he is easily distracted by events in which he is directly involved. He fails his ex-wife and son, even as he is trying to help poor junkie Dixie Peyton. His final recognition of his failings comes dramatically and brutally, and the reader is left to ponder whether he will be able to deal with his self-realization.

Dark and sad in its vision of humanity, even with the bleak humor that is scattered throughout, this dramatic and tense novel questions the relationship between freedom and responsibility, between order and justice, and between principles and expediency. The title, from a poem by Leonard Cohen, epitomizes Synnott’s dilemma: “Like a drunk in a midnight choir/ I have tried in my way to be free.”

Notes: Also reviewed here: Gene Kerrigan’s LITTLE CRIMINALS, THE RAGE, and DARK TIMES IN THE CITY

The author’s photo is from http://www.zonelivre.fr

A Dublin garda station may be seen here: http://ireland.archiseek.com

The wonderful photo of Galway is one of many equally good photos by David Robertson on his website: http://davidpj.wordpress.com