Note: This novel, released to accolades in the U.S. in 2013, won the Crime Writers Association Golden Dagger Award for Best Crime Novel of 2012. Today, May 1, 2018, publisher Europa Editions has re-released it with a new cover. The Wall St. Journal named it one of the Ten Best Mysteries of 2013. This is the review I posted on Feb. 15, 2013.

“Cozy cartels, golden circles – whatever you call them, they’re as much a part of this country as the mountains and the bogs. They watch out for each other…There’s no percentage in fighting a battle you can’t win.”

When Rose Cheney, a partner of Det. Sgt. Bob Tidey of the Dublin Police, offers these comments to Tidey, he is frantic to see that justice is done regarding some cases he has been working on, and not because he believes in some pristine concept of justice – he’d “long let go of the illusion that he was making the world a better place. It was the effort that mattered. To quietly accept the hopelessness, to fail to struggle, was to live without meaning.” Tidey, a law officer for twenty-five years, is desperate to protect some of the people he knows as good, but he believes that the deck is stacked against them, possibly exposing them to death at the hands of criminals. “Seeing in his head a sketched map of the world around him, how things were and what he had to do,” he has come up with a plan of attack against those who endanger the people and moral values he respects, and “He had to do it and he didn’t dare. It had to work and it couldn’t possibly. The consequences if he failed were dreadful, the consequences if he succeeded were hardly less so.”

When Rose Cheney, a partner of Det. Sgt. Bob Tidey of the Dublin Police, offers these comments to Tidey, he is frantic to see that justice is done regarding some cases he has been working on, and not because he believes in some pristine concept of justice – he’d “long let go of the illusion that he was making the world a better place. It was the effort that mattered. To quietly accept the hopelessness, to fail to struggle, was to live without meaning.” Tidey, a law officer for twenty-five years, is desperate to protect some of the people he knows as good, but he believes that the deck is stacked against them, possibly exposing them to death at the hands of criminals. “Seeing in his head a sketched map of the world around him, how things were and what he had to do,” he has come up with a plan of attack against those who endanger the people and moral values he respects, and “He had to do it and he didn’t dare. It had to work and it couldn’t possibly. The consequences if he failed were dreadful, the consequences if he succeeded were hardly less so.”

Writing a complex novel which is the epitome of Irish noir, author Gene Kerrigan explores the gray areas separating clearly right from clearly wrong, and blurring the lines between good and evil so completely that it is impossible to find anyone in the novel who is not, at some level, a blend of both good and evil. Standing on the O’Connell Bridge over the River Liffey, contemplating his future actions, Tidey believes that he has no safe options: a banker has been murdered, a nun’s life is in danger, and his own career is in jeopardy, regardless of whether or not he carries out the only plan of action he can think of. There was “No moral thing to do. But something had to be done.”

Ireland in the second decade of the twenty-first century is in the midst of an economic disaster. The apparently plentiful money supply has dried up, leaving mortgaged houses worth less than they’d been purchased for and their owners owing millions. Thousands of houses remain empty or unfinished. Jobs have vanished, and factories and businesses have closed, an environment ripe for skirting the law in order to make enough money to live. Tidey himself has taken a pay cut, but he knows that he, at least, will have a job. Others whom he sees every day live on the edge, while a criminal underworld flourishes and expands into new areas as living conditions deteriorate.

The new Dublin Criminal Courts Building

Now, for the first time, Tidey himself is to appear in the new Criminal Courts Building as a witness, prepared to commit perjury in a case in which two “gobshites” in their late teens or early twenties decided to mock and then take on two young “uniforms” inside a pub. The Garda beat them dizzy and put them in jail overnight. Though Tidey was present at the time, his philosophy is “When fools – in uniform or out – start a stupid fight, leave them to it.” The “gobshites,” however, turn out to have government connections, one of them the son of the Minister for Commerce and Justice, and their parents have hired legal heavyweights to fight the charges.

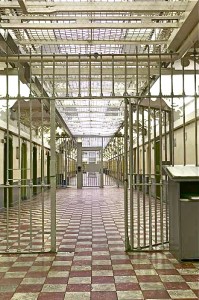

Kerrigan expands the picture of the criminal environment by including several other narratives within the novel. Vincent Naylor, only ten days out of “The Joy” for beating up a clerk in a video store while he was looking for the complete “Columbo” series for his sick grandmother, is now available for post-prison “work.” He has already committed murder for the crime bosses, though he has not been on the police radar for it. He knows that “there are two kinds of work. The routine stuff – that’s good for walking-around money…jobs that are safe and easy. Then there’s the real thing – maybe not more than a couple of jobs like that in a year.”

“The Joy,” Mountjoy Prison

Vincent has the connections and the ideas to pull a significant robbery. Unfortunately, he is also pathologically short-tempered, and this causes him continual problems – his extreme rage could even lead to loss of life, which would bring him to the attention of the Garda. While setting up the robbery, Vincent is observed from the window of a street where he has left a getaway car. Maura Coady, who has spent her entire adult life as a nun, becomes suspicious of two men leaving a car because they are both wearing plastic gloves. She calls Tidey. Her story further develops the theme of morality as a gray area. However evil one may think of Victor (who yet loves his brother and his grandmother), one thinks of Maura as the epitome of good, but she, too, has a side darker than one would expect.

The honest employees of a security company who must follow orders from a criminal; Trixie, an ex-con who saves two lives in a fire, though it means that he may be arrested; various criminals with low profiles; and members of the police hierarchy who do not want to make waves, all play roles in the ensuing action and further develop the themes. As the economic downturn gets worse, the willingness of seemingly honest people to perform acts they might not otherwise have considered increases, and the number of murders grows exponentially.

St. Mary’s Pro-Cathedral, Maura Coady’s church of choice

Kerrigan’s talent at revealing the backstories of his characters, especially that of Det. Sgt. Bob Tidey, whose own marriage has collapsed, makes all these characters more realistic than one would expect of a novel which appears at first to be primarily a story of gratuitous murder within a seemingly civilized society. Their moral quandaries, emphasized, are understandable, and are the main focus of the novel, despite the bloody violence. Harry Synnott, a former colleague of Tidey (and main detective in The Midnight Choir) makes a couple of brief appearances, and Tidey is often working with Rose Cheney, who also appeared in that earlier novel. Kerrigan elevates what might have been a traditional police procedural to a new level here. Despite the seemingly excessive number of characters and the violence, necessitating a running list of “who’s who” (for me), this novel, written in clear and unambiguous prose, achieves a higher level for the mystery story genre, one in which the emphasis on theme and character becomes at least as important for the author as the grim outcomes so common to this genre.

Also by Gene Kerrigan: THE MIDNIGHT CHOIR , LITTLE CRIMINALS, and DARK TIMES IN THE CITY

The O’Connell Bridge

Photos, in order: The author’s photo by Derek Speirs, is from

http://www.crimethrillerawards.com

The new Dublin Criminal Courts Building appears on http://www.allspecglass.com

Mountjoy Prison, “The Joy,” and a description of life inside is from http://philipconnolly.wordpress.com

The Pro-Cathedral, where Maura Coady chose to worship, is depicted on http://www.schuttersgilden.nl

The O’Connell Bridge is seen on http://www.thesun.co.uk