“There has not been a day since [my father’s] sudden and mysterious vanishing that I have not been searching for him, looking in the most unlikely places. Everything and everyone, existence itself, has become an evocation, a possibility for resemblance. Perhaps this is what is meant by that brief and now almost archaic word: elegy.”

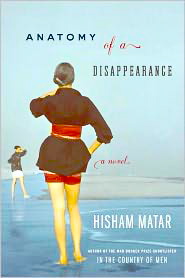

Libyan author Hisham Matar draws on his own life to provide insights into this story of a son’s yearning for the father he loved but who vanished when he was fourteen. In real life, Matar’s father Jaballa, once a member of the Libyan delegation to the United Nations and, after Muammar Gaddafi’s coup, a political dissident, went into exile in Egypt in 1979, when his son was nine. He was kidnapped in 1990, when his son was twenty. The only word the family ever received from him came in 1992, when they received two letters from him indicating that he had been kidnapped by the Egyptian secret police and handed over to the Libyan authorities where he was jailed in the notorious Abu Salim Prison in Tripoli. He was never heard from again, though word filtered out to his son that he had been seen in prison as late as 2002.

Libyan author Hisham Matar draws on his own life to provide insights into this story of a son’s yearning for the father he loved but who vanished when he was fourteen. In real life, Matar’s father Jaballa, once a member of the Libyan delegation to the United Nations and, after Muammar Gaddafi’s coup, a political dissident, went into exile in Egypt in 1979, when his son was nine. He was kidnapped in 1990, when his son was twenty. The only word the family ever received from him came in 1992, when they received two letters from him indicating that he had been kidnapped by the Egyptian secret police and handed over to the Libyan authorities where he was jailed in the notorious Abu Salim Prison in Tripoli. He was never heard from again, though word filtered out to his son that he had been seen in prison as late as 2002.

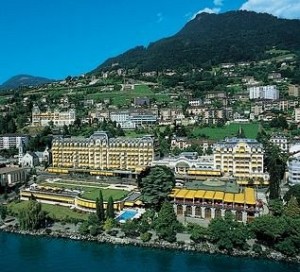

This fraught background provides the structure of Matar’s novel, which takes place in an unnamed country. Nuri el-Alfi is a young boy whose mother dies rather mysteriously when he is nine, while the family is living in exile in Egypt, and he and his father, a dissident and former minister of the government under the king, become “two flat-sharing bachelors kept together by circumstance or obligation.’ His father had refused to let his son return to their country to live with his wife’s sisters after his mother died, but he apparently feels guilty about his inability to be more of a father to him: a “tenderhearted sympathy, raw and sudden, would rise in him at the most unexpected moments, and he would plunge his face into my neck, sniff deeply and kiss, tickling me with his mustache. It would set us off laughing as though everything were all right.” When Nuri is fourteen and in boarding school in England, his father and his much younger, new wife Mona meet Nuri in Switzerland at the Montreux Palace Hotel, and it is on this vacation that his father is abducted. The Swiss police have no leads.

their country to live with his wife’s sisters after his mother died, but he apparently feels guilty about his inability to be more of a father to him: a “tenderhearted sympathy, raw and sudden, would rise in him at the most unexpected moments, and he would plunge his face into my neck, sniff deeply and kiss, tickling me with his mustache. It would set us off laughing as though everything were all right.” When Nuri is fourteen and in boarding school in England, his father and his much younger, new wife Mona meet Nuri in Switzerland at the Montreux Palace Hotel, and it is on this vacation that his father is abducted. The Swiss police have no leads.

All this information about Nuri is given in the first five pages of the novel, and as the author continues Nuri’s story from that moment up to age twenty-four, the bare bones outline of his life at the time of the kidnapping gradually broadens and gets filled in, and his life as an exile, without family or country, takes shape. Through flashbacks and reminiscences, the reader also comes to know more about Nuri’s younger life and his father’s role as a dissident in exile.

This painting by J.M.W. Turner was one of his mother’s favorite paintings, according to his father, when the two visit the National Gallery.

Scenes throughout the novel, as Nuri’s life unfolds, are abbreviated – almost lacking in description, in the sense that the author tells how people act and what they say – but the reader is required to supply images from his/her own experience. As a result, a curious kind of detachment prevails in the story-telling as the details of Nuri’s life unfold. His teenage “crush” on his stepmother, who is twenty-six when he is fourteen, is full of passion, but that passion does not translate into feelings that the reader can share, and though his sense of angst is “told about,” it does not feel “recreated” in the sense that could make scenes come alive. The closest Nuri comes to showing any real human feelings of loneliness and abandonment occurs when he is seventeen and, while on vacation from school in England, he remarks poignantly that “more than anything else, I wanted to be expected, waited for, welcomed.” He never even mentions “loved.”

Nuri persists in trying to act like a grownup at a boarding school which does not encourage him to show feelings. His personal life outside of school also has no outlet for his feelings. His father’s friends from the past have not been there to provide him with any emotional guidance, and, without a close family, this boy, living in a foreign land far from where he grew up, has no one with whom he can share anything. Even when he reaches college age, he tells us that “I kept a small radius of friends, mostly from university, with whom I shared what I imagined some siblings share: a warm alliance that still assured the necessary distance…They did not know much about me except that I came from Egypt – a fact in itself untrue. A certain kind of English temperament suited me because I was never one given to confession.”

Nuri and Hass, his attorney, go to the Federal Palace in Bern, seeking information about Nuri’s father.

It is not until he observes a man who has fallen into the water trying desperately to hang on until he can be rescued – a symbolic scene – that Nuri, at age twenty-four, starts to become “human.” The novel’s most successful scenes follow that, one of them a scene in which Nuri meets the woman from whose apartment his father was kidnapped, and learns her story. Since both of them have shared the shock of the father’s dramatic disappearance, this section, and the section in which Nuri returns “home” to Egypt for the first time in many years, have the kind of feeling that is missing in the earlier sections of the novel, perhaps indicating a belated coming-of-age.

The novel is cleanly written and straightforward, but despite the surprises in the novel, I longed to see Nuri acting like a real boy and showing a need for closeness – with someone, anyone – and especially with the reader. His stiff upper lip, in the face of the dramatic events of his life, make his narrative seem almost journalistic, and I felt excluded from his life when I wanted to share it.

Note: At one point, Nuri describes his father’s decision to go into exile, claiming: “Eighteen months after my parents employed Naima, our king was dragged to the courtyard of the palace and shot in the head. Father was a government minister by this stage, and, instead of risking ill treatment, detention or even death, he decided to flee to France.” Some critics have suggested that the author is using Iraq as his model for the unnamed country in this novel. (The king of Libya, King Idris, died in exile in Egypt at age 94.)

ALSO by Matar: THE RETURN

Photos, in order: The author’s photo by Diana Matar appears with an interview in http://www.metro.co.uk

While Nuri is on vacation with his father, after the death of his mother, they visit the National Gallery in London. His father stops and studies J. M. W. Turner’s “Calais Pier,” (1803) and, moved, tells Nuri that his mother would have loved that stormy painting, one of the only times (sadly) that he ever reminisces about his wife with Nuri after her death. http://www.paintingall.com

Nuri’s father disappears while the family is vacationing at the Montreux Palace, in Switzerland, seen here: http://www.expedia.com

After his father’s disappearance, Nuri and Hass, the family’s lawyer, go to the Federal Palace in Bern, shown here, to talk with representatives of the Federal Department of Home Affairs for information about the investigation. http://switzerlandinformation.blogspot.com/