“I can feel that great things are in store for me. But at this point, I’m sitting here with 80 marks and without a new source of income and I ask you, Where is my man for this emergency? Times are horrible. Nobody has any money and there is an immoral spirit in the air – just as you’re getting ready to hit on someone for some cash, they’re already hitting on you!” – Doris

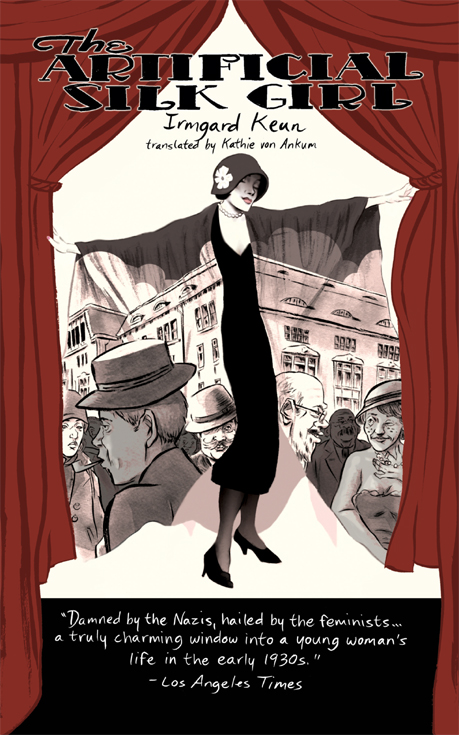

Published in Germany in 1932, when author Irmgard Keun was only twenty-two, The Artificial Silk Girl, a bestselling novel of its day, is said to be for pre-Nazi Germany what Anita Loos’s Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1925) is for Jazz Age America. Both novels capture the frantic spirit, the eat-drink-and-be-merry ambiance, and the materialism of young women like Doris and Lorelei Lee, who haunt the urban clubs as they try to work their way into a lifestyle much grander and more vibrant than anything their mothers could ever have hoped for. Many attractive young women, regardless of their education and social experience, have set their sights on becoming part of the privileged urban social scene, which they hope to achieve through the attentions of successful men with whom they flirt and often seduce. The differences between these young woman and the scorned prostitutes who hang out in the neighborhoods around the clubs blur when these young women become older, more experienced, less attractive, and more desperate.

Published in Germany in 1932, when author Irmgard Keun was only twenty-two, The Artificial Silk Girl, a bestselling novel of its day, is said to be for pre-Nazi Germany what Anita Loos’s Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1925) is for Jazz Age America. Both novels capture the frantic spirit, the eat-drink-and-be-merry ambiance, and the materialism of young women like Doris and Lorelei Lee, who haunt the urban clubs as they try to work their way into a lifestyle much grander and more vibrant than anything their mothers could ever have hoped for. Many attractive young women, regardless of their education and social experience, have set their sights on becoming part of the privileged urban social scene, which they hope to achieve through the attentions of successful men with whom they flirt and often seduce. The differences between these young woman and the scorned prostitutes who hang out in the neighborhoods around the clubs blur when these young women become older, more experienced, less attractive, and more desperate.

In The Artificial Silk Girl, main character Doris, like the author herself, starts out in a small city (like the author’s Cologne), where she wants to be an actress, while supporting herself as a stenographer. Like Lorelei Lee in the Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, Doris eventually decides to write a commentary about her life which becomes the point of view of the novel. Author Irmgard Keun refused, throughout her own life, to write an official autobiography, but her characterizations and insightful commentary about the times, both in this novel and in Gilgi, One of Us (1931), suggest that she was intimately, if not personally, aware of the social tightrope young women like Doris walked as they tried, and often failed, to improve their lives. The authorities in Germany were not pleased, however, with her published depiction of Berlin life as Hitler and the Nazis, preparing to take power, envisioned it. Within a year, Keun’s books were confiscated and all known copies were destroyed. In 1936, Keun, firmly opposed to Nazism, escaped Germany for Belgium, Holland, and later New York, not returning to Germany until 1940, when false reports of her suicide made it possible for her to enter and live in Germany under an assumed name. Though she continued writing after World War II, it is this novel, rediscovered and republished in 1979, for which she is best known.

Doris: “I look like Colleen Moore, if she had a perm and her nose were a little more fashionable, like pointing up.”

Doris, the “artificial silk girl,” has no politics, focusing almost completely on her own ambitions – finding wealthy men who will improve her life by financing a better lifestyle for her. She cadges a desired wristwatch from one potential suitor, extols the virtues of chocolates and fine clothing to others (and is sometimes rewarded), but she also fastens her clothing with rusty safety pins in case someone unattractive gets too carried away. By the age of seventeen, she has already had a year-long affair with Hubert, her first and most lasting love, but when he ignores her birthday after she’s saved up for a new dress, and fails to produce a present, she gets angry. “All he ever gave me was a little plastic frog that I would float down the river just for fun.” And when he becomes patronizing and “wallows in his own morality,” she retaliates by embarrassing him in public.

Doris: “There’s a man with fabulously clean-cut features, like Conrad Veidt when he was at the height of his career, wearing a diamond ring on his pinky, who’s looking at me from the other end of the room.”

The novel that follows from this introduction is both fun and very funny, based entirely on the persona of Doris – totally goal oriented, unafraid to take chances, willing to do anything to get what she wants, and very clever. Her voice – honest, bawdy, and surprisingly guileless – also shows her intelligence, while her pointed observations and insights into those around her give the author unlimited opportunities for unique descriptions: She comments that her father is “lazy as a dead body.” One restaurant is “a beer belly all lit up,” and dancing the tango “when you’re drunk…is like going down a slide.” There are no limits to Doris’s imagination and her self-interest, and when she seizes the opportunity to be an extra in a theatrical production, she quickly drops hints about her own background to impress people as she plots her way to success. Her feverish excitement beguiles the reader, and when her outrageous behavior forces her to escape not only the theater but the city itself, the reader cannot help but root for her eventual success.

Goldwasser, a Polish liqueur made with flakes of real gold, excites Doris: “It’s sweet and makes you drunk – it’s like a violin and tango in a glass.”

The author divides the novel into three parts, reflecting the seasons and the symbolism associated with them. The wild, spontaneous, free-for-all of action in Part I takes place at the end of summer. Part II begins in Late Fall in Berlin, a much larger city, and the reader expects that this will be a darker and probably more contemplative time. The gradual change of mood here, a true testament to the talent of Keun, increases the reader’s identification with Doris and her goals. As Doris arrives in Berlin at Friederichstrasse Station, “the politicians [both German and French] arrived on the balcony like soft black spots,” and the crowd erupted, rushing the balcony and screaming for peace as the naïve Doris asks a café patron “if Frenchmen and Jews were one and the same.” A moving scene in which Doris takes her blind neighbor for a last walk through the city before he goes to a nursing home, highlights this section and reflects Doris’s (and the author’s) ability to describe images of 1933 Berlin in ways that could only have been done by someone who was there at the time. As the old blind man says, “The city isn’t good and the city isn’t happy and the city is sick…but you are good and I thank you for that,” an amazing comment for any author to make publicly as the Nazis were coming to power.

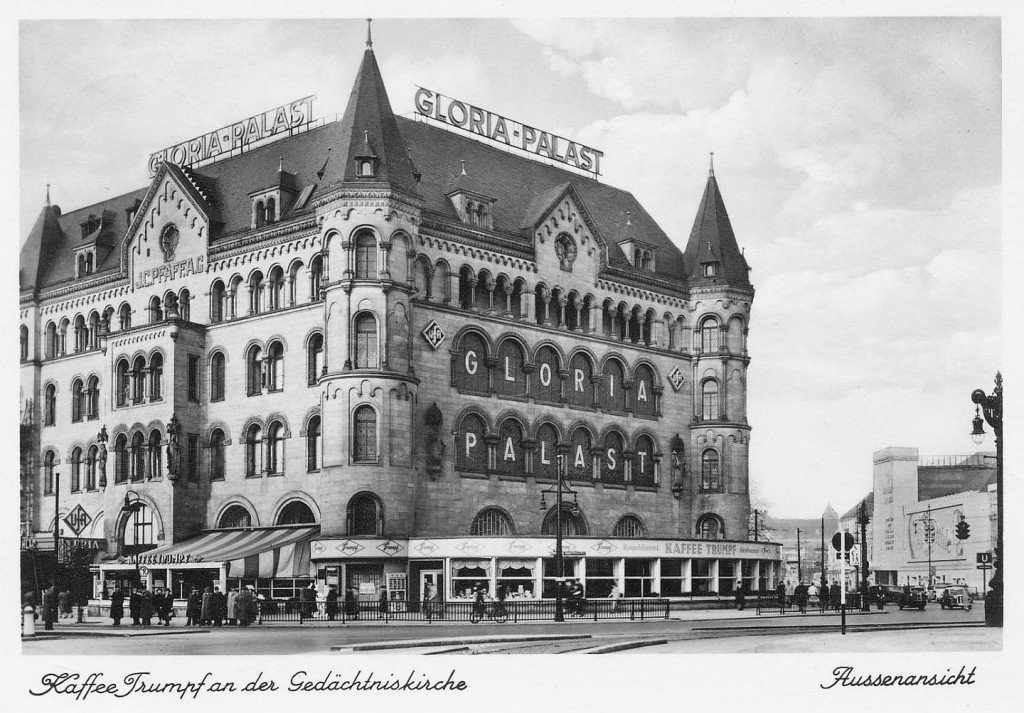

In Berlin Doris comments that “The Gloria Palast is shimmering – it’s a castle, a castle – but really it’s a movie theater and a cafe…”

Part III, “A Lot of Winter and a Waiting Room,” introduces three men, each of whom affects Doris’s life and future, bringing about new recognitions by Doris and a realistic conclusion to the novel. A tiny section in Part III carries the novel up to the Spring, suggesting new growth and, perhaps, new hope. The author’s efficient and effectively presented structure allows her to describe all manner of Berlin life during this fraught period, at the same time that it allows Doris to grow and develop naturally for the reader. The book’s timeless themes regarding women and how they see themselves, combine with history in a unique way, giving life to a less publicized period of history and new insights into some of the women who lived through it.

ALSO by Keun: FERDINAND: The Man with the Kind Heart

Note: Another, very different, novel about this same period is BLOOD BROTHERS by Ernst Haffner, also highly recommended, also banned by the Nazis in 1933, also rediscovered in the late 1970s, and also translated into English and republished by Other Press in the past two years.

Photos, in order: The author’s photo, taken when she was twenty-five, is from http://www.themillions.com/

Colleen Moore, to whom Doris compares herself, was an American actress who began in silent films and who popularized the bobbed haircut. https://www.pinterest.com/

Conrad Veidt, a popular actor in Germany, left the country for England and eventually the US, in 1933, bringing his Jewish wife with him. His career is fascinating and is summarized on Wiki. His photo is from https://conradveidt.files.wordpress.com/

Goldwasser, a Polish vodka and herbal liqueur which features flakes of real gold, was invented in Danzig in 1598 and is still available for sale. Doris enjoyed this because “It’s sweet and makes you drunk – it’s like a violin and tango in a glass.” http://galeri.uludagsozluk.com/

The Gloria Palast in Berlin “is shimmering – it’s a castle, a castle – bit really it’s a movie theater and a cafe…” http://allekinos.pytalhost.com/

ARC: Other Press