“The Internet’s a godsend to you…it’s where you feel most comfortable. There, you’re able to convince yourself you’re connected to the world, when in fact you’re protected from it, isolated, alone and safe.”–A friend, speaking to Jenny Rowan, on the job.

James Sallis is a never-ending source of surprise as a novelist. Though his minimalist prose style does not change – concise, compressed, and incisive – and his subject matter always focuses on the darkest aspects of life, his approach to his subjects varies widely. His early novels, like the John Turner trilogy, which have been combined under the single title of What You Have Left, verge on Southern Gothic. Set in Tennessee, the novels are filled with local color, but those colors are very dark, as life deals unexpected horrors indiscriminately to Turner, a damaged policeman, over the course of several years. Drive, which became a successful film, and Driven, its sequel, move the setting to Phoenix for two novels so darkly violent that they terrify with their bloody intensity. The Killer is Dying, my favorite of Sallis’s novels, also set in Phoenix, is different from the others in that all three of Sallis’s main characters, while living difficult lives at the mercy of grim outside forces, also show a resilience of spirit and the ability to deal with their situations. Sallis makes us care about them because of that, and even a hired killer inspires a little sympathy. “Strength was not about overcoming things. Strength was about accepting them,” Sallis says in that novel, a dark commentary on human nature which nevertheless allows for some hope.

James Sallis is a never-ending source of surprise as a novelist. Though his minimalist prose style does not change – concise, compressed, and incisive – and his subject matter always focuses on the darkest aspects of life, his approach to his subjects varies widely. His early novels, like the John Turner trilogy, which have been combined under the single title of What You Have Left, verge on Southern Gothic. Set in Tennessee, the novels are filled with local color, but those colors are very dark, as life deals unexpected horrors indiscriminately to Turner, a damaged policeman, over the course of several years. Drive, which became a successful film, and Driven, its sequel, move the setting to Phoenix for two novels so darkly violent that they terrify with their bloody intensity. The Killer is Dying, my favorite of Sallis’s novels, also set in Phoenix, is different from the others in that all three of Sallis’s main characters, while living difficult lives at the mercy of grim outside forces, also show a resilience of spirit and the ability to deal with their situations. Sallis makes us care about them because of that, and even a hired killer inspires a little sympathy. “Strength was not about overcoming things. Strength was about accepting them,” Sallis says in that novel, a dark commentary on human nature which nevertheless allows for some hope.

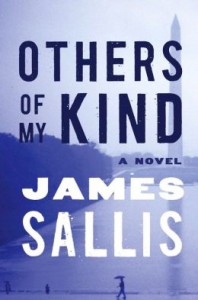

In this new novella, Others of My Kind, Sallis shows a broader development of this theme, and more hope. Strength is important, and accepting what comes is necessary, but it is also essential to recognize “the importance of letting people get on with their lives…It’s only when others turn up hell-bent on change – family, peers, people with religious, social, or political agendas – that it all goes to shit. We’re adaptable creatures. We make do. We wear the shirts we have.” It is that broader consideration of society as a whole, our roles in it, and our recognition that even the most damaged people have the power not only to accept their pasts but to move beyond them – and even, perhaps, to make lives easier for other people who have suffered – that makes this novella different from Sallis’s previous work. Life for survivors of horrors, like Jenny Rowan and Cheryl here, may never be warm and cozy in Sallis’s world, but, he observes, it is possible for them eventually to come to terms with the past, to grow beyond the effects of the horrors which have dominated their inner lives, to think about a future, and maybe, with luck, begin to see signs of hope, if not happiness.

While Jenny is held prisoner in the box, her captor gives her the classic 8-Ball toy. This one says “Outlook Not So Good.”

Using the point of view of a female victim for the first time, and setting the story in a chaotic near future, Sallis introduces Jenny Rowan’s back story (all of which happened before the novel opens). Jenny now uses an assumed name, chosen after she was held prisoner from the age of seven to the age of nine, confined to a wooden box under the bed of her kidnapper, who viciously assaulted her sexually for two years. When she eventually managed to escape, she hid in the Westwood Mall for two years, scrounging for food and discarded clothing, until she was discovered by social services and assigned to a juvenile facility until her sixteenth birthday. Aid from an elderly woman after she was released led to a job, and she also went on to school and received a degree. Throughout, she recognizes the help she has received from good people who allow her to make her own decisions, and eventually she finds the perfect job, working for a TV station where she spends all day alone in a dark office finding snippets of stories on the internet and then combining them into features for the evening news. It is in this job that Jenny is working when the novella opens, and she quickly becomes real for the reader, who begins to care deeply about her future.

Jenny found plenty of places to hide and find food during her two years living in a mall. Photo by Peter Kaminski

Sallis seizes life here and twists it way beyond all norms, establishing easily identifiable themes about a victim’s emotional survival and strength, her tenuous steps into society, her need to progress at her own pace, and eventually her ability to reach out and help “others of [her] kind.” The focus is metaphorical, even allegorical, and the book is less realistic, more symbolic, than we are accustomed to with Sallis: After two years of captivity, begun when she was seven, for example, Jenny has somehow forgotten her name, address, the names of her parents, where she went to school, and everything else from her early childhood, the reasons for which are never explained, though her torture took place long after those formative, usually permanent, memories. She succeeds in keeping herself hidden for two years while living in the Westwood Mall without ever being caught by security or reaching out. She catches up on her schooling in the juvenile facility so successfully that she earns an Associate’s Degree while working full-time over the next few years. When the novella’s real action starts, Jenny begins slowly to connect with other people, one of whom is a major political figure during a time of social turmoil, that friendship further emphasizing the symbolism as it relates to well-meaning people who work for change through political, social, and religious agendas.

Several people who supposedly don’t know Jenny’s past have somehow learned about it but say nothing to her, a device which advances the plot and allows them to help her secretly. Some of these real-life helpers become the equivalent of angels, while those who deliberately hurt her appear as monsters from some cruel netherworld. “At some point,” Jenny observes, “we realize that [change is] not going to ‘just happen,’ that we’re going to have to make the decision to become human and put some effort into it…We work at making a self for most of a lifetime, only to find that the self we’ve created is inseparable from the struggle.” As she lives each day, she continues to struggle, resisting closeness for fear of also losing control.

Eventually, Jenny wants to conclude her story, but she has difficulty doing so. Even she recognizes that her unlikely relationship with a powerful political person is an element about which others might say, “Wow. And hand me a tissue.” But she also observes that “America is as much idea as actuality…the state with its grand ideals must look away from whatever belies those ideals. Henry James claimed that in America each new generation is a new people. Each day here is also a new day, unburdened by history, rife with promise.” With this unusual novel, which balances subtle themes within a less subtle metaphorical framework, James Sallis goes in some optimistic new directions, with themes which may be further developed in novels to come.

ALSO by James Sallis: DRIVE, DRIVE (the film), DRIVEN (the sequel to DRIVE), THE KILLER IS DYING, WHAT YOU HAVE LEFT (John Turner Trilogy), WILLNOT, SARAH JANE

Photos, in order: The author’s photo is from a video on http://vimeo.com

The 8-Ball toy, with the “fortune” of “Outlook Not So Good,” appears on http://thetolerantvegan.com Danny, Jenny’s kidnapper, gave this to her as her only toy for the two years she was imprisoned.

The Perimeter Mall may be found on http://commons.wikimedia.org Photo by Peter Kaminski

The baby of the squatters who live beside Jenny is said to resemble a limp doll. http://grandmastrash.blogspot.com

ARC: BLOOMSBURY