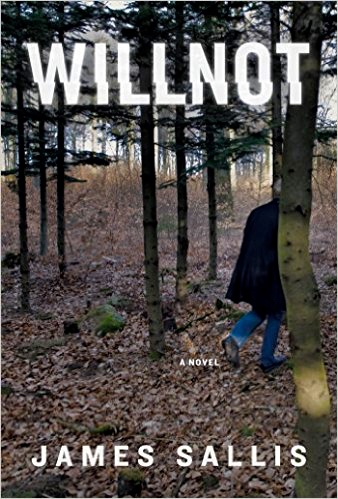

“People in Willnot tend to dwell at the thin edge of maps, more than a few of them staring tygers in the eye. Something in their nature that draws them here, keeps them here? Or that seeps in over time from contact? Stand them up against a straight line, and they’ll lean. There are no churches in Willnot. A string of them outside the town limits but none within, by ordinance.”

For long-time readers of this website, it will be no secret that I regard James Sallis as far more than the “noir mystery writer” that he is often labeled. A specialist in spare, minimalist writing that is compressed, incisive, and often metaphorical, he is a writer who takes literary chances and whose recent work has been as experimental as it has been insightful. One of the best literary writers in the United States, in my opinion, Sallis has always been concerned with questions of innocence and guilt, strength and weakness, and the past and its effects on the present and future. He creates often sad, damaged characters doing the best they can in a noir atmosphere in which they must fight their own demons in order to have any chance of success. His earliest novels, a series of mysteries set in the southern United States, are dark and gothic without the sentimentality so common to that genre, and his later books, set in the west, are more psychological, stories of people living on the edge whose lives could go in any direction depending on chance and circumstance. His main characters make mistakes, sometimes big ones, but at heart they have an intrinsic sense of honor despite their closeness to violence.

For long-time readers of this website, it will be no secret that I regard James Sallis as far more than the “noir mystery writer” that he is often labeled. A specialist in spare, minimalist writing that is compressed, incisive, and often metaphorical, he is a writer who takes literary chances and whose recent work has been as experimental as it has been insightful. One of the best literary writers in the United States, in my opinion, Sallis has always been concerned with questions of innocence and guilt, strength and weakness, and the past and its effects on the present and future. He creates often sad, damaged characters doing the best they can in a noir atmosphere in which they must fight their own demons in order to have any chance of success. His earliest novels, a series of mysteries set in the southern United States, are dark and gothic without the sentimentality so common to that genre, and his later books, set in the west, are more psychological, stories of people living on the edge whose lives could go in any direction depending on chance and circumstance. His main characters make mistakes, sometimes big ones, but at heart they have an intrinsic sense of honor despite their closeness to violence.

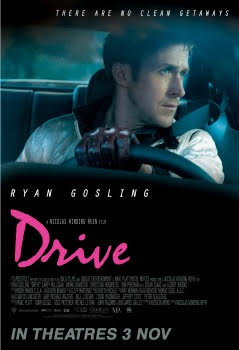

What is most striking about Sallis’s work is that it is never static. His career of sixteen novels and numerous story collections, from the southern gothic novels to Drive, made into a successful noir film, continues to develop as he experiments with style and structure. An author who refuses to become comfortable or predictable in his writing, he reveals his most experimental and his most compressed style in this latest novel, Willnot. Shifting his points of view and using flashbacks and flashforwards, the idea of time itself becomes flexible, and as the action develops, the reader becomes as uncomfortable as the main character, not really sure what is real and what may be imagined. Ultimately, in the conclusion, Sallis leaves it up to the reader to fill in the blanks of this complex story in order to find resolution to the problems and disasters which have marked the lives of his characters.

A recent novel by Sallis is DRIVE, which was made into a hit film in 2011, starring Ryan Gosling.

Willnot, a rural town in an unnamed state, has, as the quotation at the opening of this review notes, attracted people who “dwell on the thin edge of maps,” resourceful people who, though damaged by the horrors that life has often thrown in their paths, still rely on their own inner resources and try to find answers without the aid of churches or outside agencies. Main character Lamar Hale, a physician who has lived in Willnot for many years, is one of over thirty characters introduced in the first thirty-two pages, illustrating the fact that there are no strangers in Willnot – Hale knows everyone. As Sallis individualizes these characters, Hale’s feelings about them become clear, and the reader comes to know the town well. Many have secrets, including Lamar Hale who treasures his memories of his father, a science fiction writer who knew the greats of that genre, though Hale has recently begun to wonder about the nature of his father’s writing and whether it might have been political, and even dangerous.

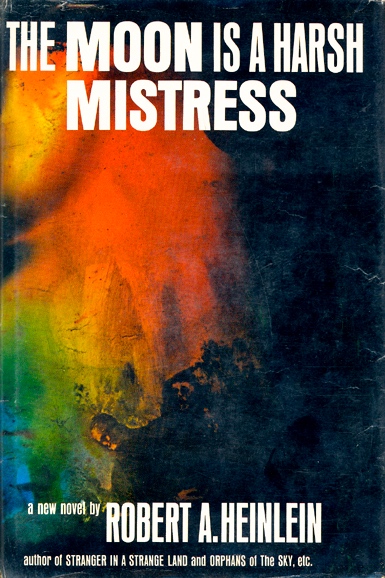

THE MOON IS A HARSH MISTRESS, a sci-fi novel by Robert A. Heinlein, a friend of Hale’s father, is one Hale wanted to discuss with the author. It is concerned with the development of a future human society on earth and the moon.

The novel opens at a crime scene, as one of Hale’s neighbors and his hunting dog have uncovered what appears to be the site of a mass burial. Called to the scene, Lamar Hale is there to assist the sheriff, and as he chats with Andrew, who runs the ambulance service, he is reminded about his work with Andrew when Andrew was a teenager dealing with ADD and the drugs that were once prescribed for it. Returning to the hospital after the bodies have been unearthed, Hale is transcribing his notes when he is startled by the arrival of Brandon Roemer Lowndes, someone he has not seen in fourteen years. Years ago, Brandon had ended up at the “wrong end of a prank gone horribly south,” when he took the high school band’s bus to a football game and came back in an ambulance, in coma. Hale treated him for the year it took for him to regain consciousness. Lowndes eventually left Willnot, but has now come back following his time in the Marines, where he served in Afghanistan and Iraq. Now known as Bobby, he says he has just come back to say hello. His additional surprise visits to other places in town are as mysterious as his sudden appearance at Hale’s office.

The Brothers Karamazov, by Dostoevsky, fascinated Hale for its depictions of the abyss of loneliness and degradation and the equal abyss of lofty ideals, two competing ideas with the same results.

Focusing on the local residents and their thinking, the reader also learns about Hale’s partner, Richard, who is a teacher, and about other people whose lives have been difficult, including a young woman who was abandoned by her parents and brought up by foster parents, and a young man whose parents and sister died in a hit-and-run car crash which has left him obsessed with finding the driver, to the exclusion of everything else in his life. Even Lamar Hale has some sad memories, always feeling he was a disappointment to his author father. Gradually, the lives and memories of various characters begin to overlap, and since the author sometimes changes the point of view without warning – and between paragraphs – it is easy to become confused about which person is remembering or thinking about which events. The overlaps between the lives of Brandon Lowndes (Bobby) and Lamar Hale raise questions about how and why each of them has become who he is, the question at the heart of the novel. References to literature, including the Brothers Karamazov, with its religious imagery – the abyss of lowliness and degradation, and its parallel, the abyss of lofty ideals in a community which has no churches – add to the mysteries.

The writing throughout is superb, and most readers will be fascinated by the characters, their thinking, and their ways of dealing with reality. I have now read the book twice and have read some sections three times, always trying to identify the points of view in relation to the characters so that I can put the whole novel into the wider perspective it deserves. I am still working at it. This is by far the most complicated of Sallis’s novels in terms of his themes and his insights into character, and I have been totally engrossed by it. Though I hate the very word “closure,” I’m hoping I soon achieve it for this novel by this very special author.

ALSO by Sallis: DRIVE, DRIVEN, THE KILLER IS DYING, OTHERS OF MY KIND, WHAT YOU HAVE LEFT, SARAH JANE

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on http://www.flickeringmyth.com

The poster from the film DRIVE, based on Sallis’s novel of the same name, is from http://jamiegerrisha2.blogspot.com

The science fiction novel THE MOON IS A HARSH MISTRESS by Robert A. Heinlein is one of particular interest to Hale when he was a boy. Heinlein was someone known to Hale’s father, also a writer of science fiction, and Hale had hoped to discuss this book, about a society for humans on both the earth and the moon, with the author. https://en.wikipedia.org

Hale was always intrigued by the image in THE BROTHERS KARAMAZOV by Dostoevsky of the abyss of loneliness and degradation and the equal abyss of lofty ideals, two competing ideas with the same result. www.amazon.com/

Hale’s constant work in the local hospital where he worked as a surgeon, primary care physician, and psychiatrist, kept him in touch with the lives of the town and their efforts to stay emotionally healthy in spite of the disasters they all faced. http://news.wabe.org/

ARC: Bloomsbury