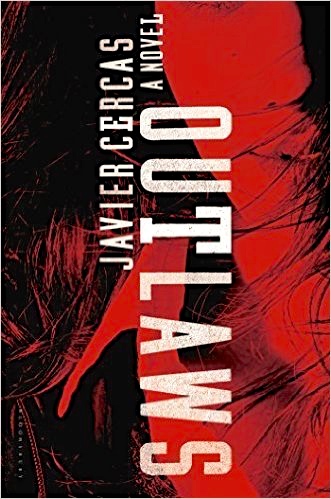

Note: This book is SHORTLISTED for the Dublin International Literary Award, formerly the IMPAC Dublin Literary Award, the richest prize in the writing world, in 2016.

“I never felt entirely like just one more member of the gang: I was and wasn’t, I did and didn’t, I was inside and out, like a witness or onlooker who participated in everything but most of all watched everyone [else] participate…Aside from Zarco and Tere…I barely spoke to anyone on my own, and I wasn’t close to any of them. For all of them I was…a meteorite, a disorientated kid, a posh brat lost among them…” –Gafitas, aka Ignacio Canas.

Opening in 1978, three years after the death of Spain’s Generalissimo Francisco Franco, this stimulating and provocative novel comes to life through the point of view of Gafitas, a naïve, middle-class sixteen-year-old drawn into the alien world of Zarco, a school dropout who lives in the poorest section of the city of Gerona, in the far northeast of Spain. With no guidance, no prospects, no hope, and no future, Zarco and his friends have only the miserable present to look forward to, and their primary goals are to do the best they can with what they have and to take what they don’t have if they can get away with it. Forming a gang of quinquis, they commit petty crimes, and as the novel opens, Gafitas, cruelly bullied by his former school friends, has made informal contact with them during his school vacation. Dazzled by Tere, who may or may not be Zarco’s lover, he is easy prey for the gang, which needs an innocent-looking accomplice for a robbery.

Opening in 1978, three years after the death of Spain’s Generalissimo Francisco Franco, this stimulating and provocative novel comes to life through the point of view of Gafitas, a naïve, middle-class sixteen-year-old drawn into the alien world of Zarco, a school dropout who lives in the poorest section of the city of Gerona, in the far northeast of Spain. With no guidance, no prospects, no hope, and no future, Zarco and his friends have only the miserable present to look forward to, and their primary goals are to do the best they can with what they have and to take what they don’t have if they can get away with it. Forming a gang of quinquis, they commit petty crimes, and as the novel opens, Gafitas, cruelly bullied by his former school friends, has made informal contact with them during his school vacation. Dazzled by Tere, who may or may not be Zarco’s lover, he is easy prey for the gang, which needs an innocent-looking accomplice for a robbery.

In the course of the summer, Gafitas experiments with drugs, sex, and the excitement of behaving in a way that is totally alien to everything his family believes in. His resentment of his father and his father’s rules make Gafitas’s participation in robberies and car thefts both exciting in their own right and exciting for the “freedom” he experiences. It gives away nothing for anyone who reads the book’s endnotes or the summaries of this book in reviews and on Amazon, to reveal that the first part of the book ends when an armed bank robbery by the gang goes bad and the police appear in force. Shooting breaks out and, the wounded Zarco, who is running with Gafitas at the time, insists that Gafitas escape, since Gafitas has never really been part of the gang anyway. Simultaneously crushed by this revelation and full of guilt at abandoning his “friend,” Gafitas returns home and re-enrolls at school at the end of the vacation. No one there knows about his unusual summer activities.

In the course of the summer, Gafitas experiments with drugs, sex, and the excitement of behaving in a way that is totally alien to everything his family believes in. His resentment of his father and his father’s rules make Gafitas’s participation in robberies and car thefts both exciting in their own right and exciting for the “freedom” he experiences. It gives away nothing for anyone who reads the book’s endnotes or the summaries of this book in reviews and on Amazon, to reveal that the first part of the book ends when an armed bank robbery by the gang goes bad and the police appear in force. Shooting breaks out and, the wounded Zarco, who is running with Gafitas at the time, insists that Gafitas escape, since Gafitas has never really been part of the gang anyway. Simultaneously crushed by this revelation and full of guilt at abandoning his “friend,” Gafitas returns home and re-enrolls at school at the end of the vacation. No one there knows about his unusual summer activities.

Throughout Part I, Spanish author Javier Cercas reveals the action of 1978 through interviews conducted by a journalist who is currently writing a book about Zarco, thirty years after the action of 1978. Interviews with Gafitas alternate with the same journalist’s interviews of an Inspector Cuenca of the Gerona Police, who helped thwart the robbery from which Gafitas escaped years ago. The inspector’s commentary and the journalist’s questions provide additional perspectives on those same events and broaden the scope of the novel beyond that of a thriller. Gafitas’s view of what happened also includes conversations with Zarco, the women involved with the gang, and Gafitas’s family, giving even more visions of “the truth” and establishing the themes of the novel very early. In Part II, the same journalist continues his interviews, bringing the action up to date, thirty years later. Gafitas, now known universally by his real name, Ignacio Canas, is a highly successful lawyer in his early forties who has never publicly revealed his “summer of 1978.” Interviews with Gafitas/Canas alternate in Part II with those of Eduardo Riquena, who is the superintendent of the prison in Gerona, and he becomes a major character here when Zarco/Antonio Gamallo hires Canas to represent him in a suit against the legal system. Throughout this section, the author keeps the reader up to date on what has happened to the rest of the characters from Part I, often giving hints and creating a sense of foreboding.

Monument to General Alvarez de Castro, who in 1808 joined the Spanish rebels against the French. Under Alvarez, the Spanish held out against a siege for seven months though outnumbered 4:1. References to Alvarez de Castro appear in both the opening pages and in the conclusion. See Note with photo credits for symbolism. Photo by D. Timmermans.

Highly literary in its approach to the subjects of identity, moral responsibility, and truth as each person sees it, the novel illustrates how a person’s past influences his perception of the present and how that, in turn, influences that person’s actions which affect the future. Canas introduces themes in the first chapter of Part II when the journalist comments that since Canas was a delinquent and is now a lawyer that he must know, first hand, both sides of the law, to which Canas replies: “A lawyer and a delinquent are not on two different sides of the law…a lawyer is an intermediary between the law and the delinquent. That converts us into morally dubious types: we spend our lives with thieves, murderers, and psychopaths and, since human beings function by osmosis, it’s normal that the morals of thieves, murderers, and psychopaths end up rubbing off on us.” Complicating matters, Canas points out that once the press becomes involved in reporting the tales of a criminal, the criminal is often perceived as some kind of “good delinquent,” thereby acquiring mythical stature which changes the public’s perception of who that person really is for a generation or more. Zarco’s myth still hasn’t ended, even thirty years later: “The proof is that here we are, you and I, talking about him,” Canas says, noting that the journalist is also getting ready to release a book that may continue the myth.

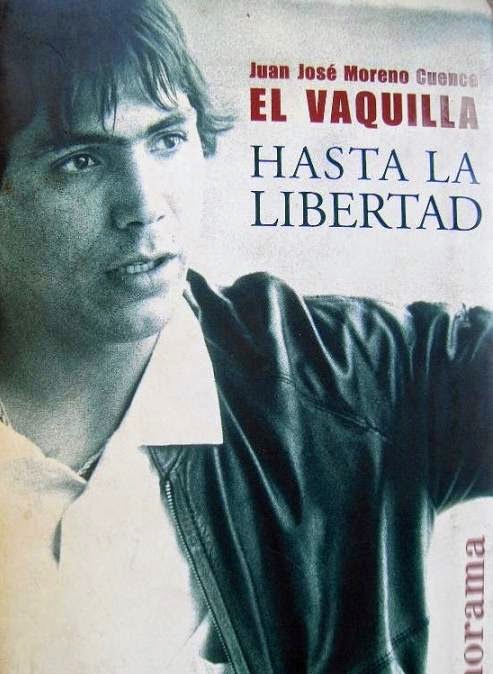

The depiction of Zarco is inspired by the memoirs of Juan Jose Moreno Cuenca, an outlaw who was active in Spain during the 1970s.

The Author’s Note at the end of the novel provides additional insights into the writing of this book. The first source which the author mentions as important to him is a book called Hasta la Libertad by Juan Jose Moreno Cuenca. That book, according to Wiki and other sources, consists of the prison memoirs of a real person, one of the most legendary criminals in Spain, and he is widely regarded as the inspiration for the character of Zarco here. In an especially ironic twist, the author of Outlaws also gives the police inspector the name of the real criminal, Cuenca. Perhaps as a result of having been based on a real person, Zarco comes alive in terms of the ups and downs – moral, physical, psychological, and legal – with which he, and by extension Canas and the journalist, must cope over the course of thirty years. The book becomes intensely introspective as Cercas explores his themes from the points of view of Canas, Zarco, and the female gang members supporting the gang. Both Canas and Zarco eventually come to some new understandings in the course of the novel. The journalist, however, may present a problem with the truth, depending on whether he believes in Zarco’s myth and wants to publicize it. As Canas says, “Frivolous journalists lie but everyone knows they lie and nobody pays them any attention, or hardly anyone; serious journalists, however, lie while shielding themselves with the truth, and that’s why everyone believes them. And that’s why their lies do so much damage.”

ALSO by Cercas: SOLDIERS OF SALAMIS

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears in http://www.parismatch.com/

The map of Catalonia may be found on http://www.spainthenandnow.com/

The memorial to Gen. Alvarez de Castro, photographed by D. Timmermans, may be found on http://napoleon-monuments.eu/ References to the general occur at the beginning of the novel and in the last pages, showing the impossibility of ever knowing the absolute truth. When Cuenca was young, he regarded Gen. Alvarez as a “fabulous hero,” which was why he asked to be posted to Gerona after he completed his police training. Many years later, when he revisited the story of Alvarez, he concluded that he was a “disgusting character, a psychopath,” coming to the ironic conclusion that “the best thing that happened in my life [coming to Gerona] happened to me due to a misunderstanding…and because I thought a villain was a hero,” an unusual conclusion on the subject of accepting and moving on.

Many photos related to the life of Juan Jose Moreno Cuenca, including the picture of his book shown in this review, are displayed on http://elcomentamierda.blogspot.com