Note: Irish author John Banville has used the same characters in three novels: ECLIPSE (2000), SHROUD (2002), and ANCIENT LIGHT (2012). The three novels, which may be considered a trilogy, all deal with the same themes, and Banville expands them in new directions within the three novels. My review of ECLIPSE is found on Amazon, here: http://www.amazon.com . This review of SHROUD may interest Banville fans as a lead-in to his wonderful new book. ANCIENT LIGHT, which is a separate listing.

“Fury and fear, these are the fuels that drive me, mixed in equal measure: fury at being what I am not, fear of being found out for what I am. If, one day, one or other of these forces should run out, the violent equilibrium sustaining me will fail and I shall collapse, or fly off helplessly–like a slipped balloon.”–Axel Vander

fear, these are the fuels that drive me, mixed in equal measure: fury at being what I am not, fear of being found out for what I am. If, one day, one or other of these forces should run out, the violent equilibrium sustaining me will fail and I shall collapse, or fly off helplessly–like a slipped balloon.”–Axel Vander

Axel Vander tells us from the opening of this sensitive and tension-filled study of identity that he is not who he says he is, that he has assumed another man’s identity. A respected scholar and professor at a California college, Vander is recognized by the literati for his thoughtful philosophical papers and books, especially his ironically entitled The Alias as Salient Fact: The Nominative Case in the Quest for Identity. Just before he leaves for a conference on Nietzsche in Turin, however, he receives a letter from a young woman in Antwerp, raising questions about his real identity and asking to meet with him. He agrees to meet her in Turin, and as the novel unfolds, we come to know more about the “real” Axel Vander and more about his mysterious correspondent, the disturbed Cass Cleave, whose madness does not preclude the truth of her discoveries.

Like many of Banville’s other narrators, the elderly Axel Vander of Shroud is hugely self-concerned but not self-aware. Consummately venal, he is a character who blithely takes advantage of whatever circumstances arise, with no concern for the consequences, except to himself. “Mendacity is second, no, is first nature to me,” he says. “All my life I have lied. I lied to escape, I lied to be loved, I lied for placement and power; I lied to lie. It was a way of living.” Now, facing the possibility that Cass possesses some damaging knowledge of his early life, he wonders “if other people feel as I do, seeming never to be wholly present wherever I happen to be, seeming not so much a person as a contingency, misplaced and adrift in time.” He shares neither the past nor the core values which allow the rest of us to be part of our societies.

Crucifixion by Lucas Cranach, the Elder

Though Vander regards Cass Cleave as mad, she and Vander develop a relationship of almost religious significance. He is a depraved and amoral old man living a life of personal un-truth, while she is a sick, avenging angel, striving to connect the disjunctions in her life so that she can become an integrated, whole person. In Turin, where she joins Axel, she sees religious symbolism in common events, finding an ordinary breakfast a form of communion: “[The waiter] lifted the paper crown from the orange juice with a strange, grave movement of his hand, like a priest lifting the white cloth from the chalice….It was as if she had been submerged in something dense and dark and suddenly had risen up and broken soundlessly through the surface into the light, the radiance.” By the end of breakfast, she sees herself as “the priestess bound to the shrine [Vander] by immemorial, unbreakable vows. She even had her sacred scepter, in the form of a fountain pen…”

Banville further develops the religious symbolism by his references to artworks, crucifixion scenes by artists from the various settings in which the novel takes place: Cranach, Bosch, Memling, and Van Eyck in his scenes from Antwerp and the North Countries, and Tintoretto, Mantegna, and Bellini in scenes from Italy. Always present in the background, of course, is the Shroud of Turin, which may be the real burial cloth of Jesus–or may not. Several scenes of Vander lying in bed, with the covers pulled up to his chin, bear unmistakable parallels with the images of Christ at his death. One character comments on a chapter title, “Effacement and Real Presence,” from Vander’s most famous book, pointing out that the Shroud with its image of Christ’s face, is a form of “effacement,” both hiding and revealing the face, an ironic reference to the real and the absence of the real, in the Shroud and in Vander’s life.

Banville’s novel is intense, highly compressed in its development of overlapping themes, and filled with suspense, both real and intellectual. The plot, though entertaining and often exciting, reveals the dark, interior worlds of Vander and Cass so fully that a more detailed plot summary might jeopardize the reader’s own pleasure of discovery. Banville is a master craftsman who has interconnected every plot detail with his themes of identity and selfhood, the relationships we create with the outside world, and our desire to be remembered after our deaths. References to Nietzsche, to Svidrigailov (an evil character in Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment), and to Harlequin appear and reappear as Vander’s life unfolds, and they offer striking contrasts to the religious elements and the soulful self-examinations of Cass Cleave, at the same time that they place Vander in a larger, literary context.

Portovenere, where Cass Cleave died

In exquisite prose, Banville creates suspense by introducing details at a snail’s pace, conveying attitude, and acutely observing sensuous details and physical reactions. Often darkly humorous (“Nothing like a good, deep chestful of cigarette smoke to quell a morning cough…”), he satirizes novelists of local color (“Give me [instead] an anonymous patch of asphalt…”), and juxtaposes unlikely events from different times to convey information, providing voluptuous descriptions which contain both an idea and its antithesis simultaneously. In an especially ironic love scene, for example, Axel alternates details of lovemaking with those of a mercy killing, while in another he describes the death of an unknown pedestrian, then thinks about his dead wife — “Only in death has she begun to live fully for me.” Major surprises occur in the final five pages, not inserted as literary tricks, but generated naturally out of the action and interactions. This is a challenging and fascinating novel, beautifully crafted and rewarding on every level as it studies issues of identity and our memories, both real and invented.

Also by Banville, reviewed here: THE INFINITIES, THE SEA (Booker Prize), THE UNTOUCHABLE, ANCIENT LIGHT, APRIL IN SPAIN

John Banville also has a series of mysteries written under the name of Benjamin Black. Those are listed separately under Benjamin Black’s name at the Authors tab.

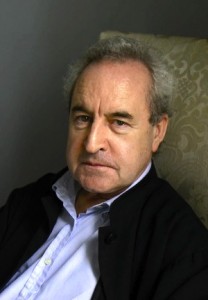

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on http://untitledbooks.com

The Crucifixion by Cranach is one of the Flemish paintings to which Vander refers as he creates religious symbolism during this time with Cass. http://theredlist.fr

The Shroud of Turin appears here: http://catholicexchange.com

The Harlequin photo appears here: http://heroeswiki.com

Portovenere, part of Liguria, is from http://londonspagirl.blogspot.com