“Remember my story? I had a story.

A beginning, a middle, and an end.

I told my story, I sang it, I meant it,

It was my only story,

And now I repent it.

All that I knew, I thought it was true,

I don’t know anymore what I think,

And do you?”

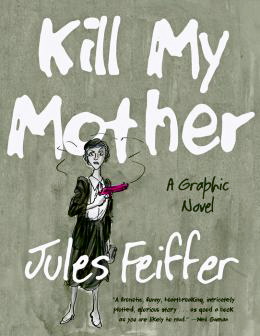

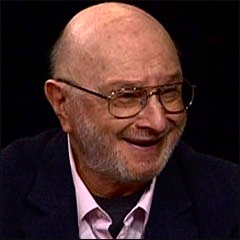

The enigmatic ending of this poem sums  up the action and presentation in this noir graphic novel, the first such attempt by the legendary Jules Feiffer. Now eighty-five, Feiffer has already won prizes in all the many genres in which he has worked: The George Polk Award for his cartoons, a 1961 Academy Award for the short animated film Munro, the Obie for the play Little Murders, the Outer Circle Critics Awards for another play of The White House Murder, and the Pulitzer Prize for his political cartoons. For good measure, he has also won the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Writers Guild of America and the 2012 John Fischetti Lifetime Achievement Award for his edgy editorial cartooning. Still active and anxious to start something new, Feiffer says in an interview* that as he aged into his eighties, he found his interests “shifting back to what I loved most: the classic adventure strips of Will Eisner’s The Spirit and Milton Caniff’s Terry and the Pirates,” something he began to explore more fully and which led eventually to this full-length graphic novel.

up the action and presentation in this noir graphic novel, the first such attempt by the legendary Jules Feiffer. Now eighty-five, Feiffer has already won prizes in all the many genres in which he has worked: The George Polk Award for his cartoons, a 1961 Academy Award for the short animated film Munro, the Obie for the play Little Murders, the Outer Circle Critics Awards for another play of The White House Murder, and the Pulitzer Prize for his political cartoons. For good measure, he has also won the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Writers Guild of America and the 2012 John Fischetti Lifetime Achievement Award for his edgy editorial cartooning. Still active and anxious to start something new, Feiffer says in an interview* that as he aged into his eighties, he found his interests “shifting back to what I loved most: the classic adventure strips of Will Eisner’s The Spirit and Milton Caniff’s Terry and the Pirates,” something he began to explore more fully and which led eventually to this full-length graphic novel.

Here Feiffer tries to do it all. Dedicating the novel to writers Milton Caniff, Will Eisner, Dashiel Hammett, Raymond Chandler, and James M. Cain and to film directors John Huston, Billy Wilder, and Howard Hawks, and their many classic films (Maltese Falcon, The Big Sleep, Double Indemnity, Mildred Pierce), Feiffer attempts to create a full-scale noir novel, with all its dark action and sad characters, and then bring it to life visually in black and white drawings for dramatic, rather than purely literary, effect. The result is an unusual and challenging novel, full of adventures affecting down-at-the-heels characters, plenty of violence of the “blam, blam, blam” variety, some grim humor, lots of “ha, ha, ha, ha” moments, twists and turns regarding plot and characters, and surprises galore.

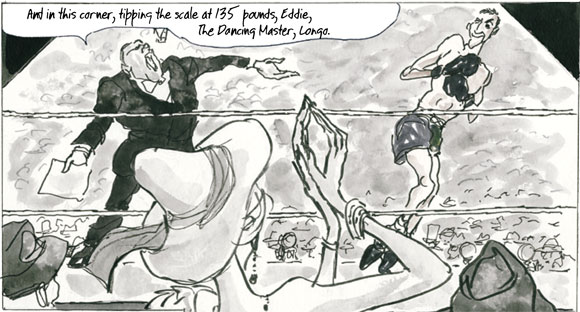

Part I, Bay City Blues, 1933, features Annie Hannigan, a jitterbugging, shoplifting teen who wants to kill her mother for returning to work to support them after her father, “the only honest cop in the history of prohibition,” was murdered. Her mother Elsie has taken a job as a typist/receptionist for Neil Hammond, a drunkard who specializes in “confidential investigations” and in demeaning behavior and sexist remarks, often directed toward Elsie. She stays on the job because Neil has promised to help her solve her husband Sam’s murder. The job becomes more complicated when Neil assigns Elsie to set up a phony casting office to try to find a tall, blonde woman, over six feet tall, being sought by a wealthy client. Later, Neil, in debt to former bootlegger Tim Gaffney, indulges his gambling habit by requiring Elsie to accompany him to a prizefight, depicted with suitably action-packed graphics featuring lightweight fighter Eddie “The Dancing Master” Longo, and leading to the discovery of the client’s true identity.

Part I, Bay City Blues, 1933, features Annie Hannigan, a jitterbugging, shoplifting teen who wants to kill her mother for returning to work to support them after her father, “the only honest cop in the history of prohibition,” was murdered. Her mother Elsie has taken a job as a typist/receptionist for Neil Hammond, a drunkard who specializes in “confidential investigations” and in demeaning behavior and sexist remarks, often directed toward Elsie. She stays on the job because Neil has promised to help her solve her husband Sam’s murder. The job becomes more complicated when Neil assigns Elsie to set up a phony casting office to try to find a tall, blonde woman, over six feet tall, being sought by a wealthy client. Later, Neil, in debt to former bootlegger Tim Gaffney, indulges his gambling habit by requiring Elsie to accompany him to a prizefight, depicted with suitably action-packed graphics featuring lightweight fighter Eddie “The Dancing Master” Longo, and leading to the discovery of the client’s true identity.

Part II, “Hooray for Hollywood” takes place ten years later. Annie Hannigan is in Hollywood as a comedy writer-producer of a show called “Shut-Up, Artie,” named for her timid boyfriend from Part I, and broadcast on radio to the troops fighting overseas. Artie, her ex-boyfriend, is now a soldier in the jungle. Ironically, Annie now has a small son, Sammy, who throws tantrums because he loves and wants his granny, Elsie, who works in a low-paying job at a movie studio, where Eddie Longo is now a star in B-movies and Tim Gaffney is hanging around looking for attention. A USO trip to the island of Tarawa brings much of the action to a head.

The novel vividly depicts the atmosphere and the cultural attitudes of the 1930s and 1940s, both in terms of its overly complicated plot and frantic action, and in terms of the drawings which accompany it. The almost hallucinogenic activity on the page can be headache-making as the pages’ irregularly shaped frames impinge upon each other and compete for attention against white dialogue balloons. The sharp contrasts within the illustrations, and Feiffer’s quick sketches, force the reader to go faster and faster to keep up with the story, and for me, at least, much was lost in this hurried process. The dialogue, written in small print, is forced to compete against much larger, black “Ha-Ha-Ha-Ha’s” “B-O-O-O-O’s” “Oh, Shut-Ups,” and dozens of “BLAM! BLAM! BLAM!’s” written within the frames, and in one six-page section, forty BLAM!s in large print dominate the drawings in which an especially important scene is taking place in the dialogue.

Ultimately, I ended up reading this book three times to be sure I really understood what was happening, and I’m still not sure I did! Part of the problem is that the female characters, though differentiated by personality, look very similar visually, especially when rendered in black-and-white, and I had a difficult time keeping them straight, especially when Part II happens ten years later, and the characters have all aged. With much happening within a Hollywood atmosphere, where costumes and disguises are a way of life, the problems of who is who becomes even more challenging. Those who love frantic, action-packed novels and films will probably love this for its movement, its wild plot twists, its dark humor, and its lack of subtlety. Those who prefer a slower, more measured development, may end up reading it three times.

*An interview with Jules Feiffer is on: (http://www.newyorker.com

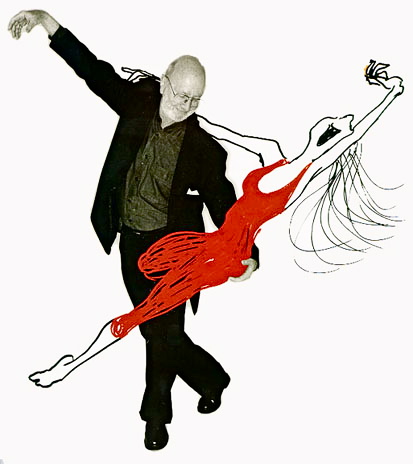

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on http://robot6.comicbookresources.com/

The author’s dancing photo is from http://robot6.comicbookresources.com/

The prizefighting photo from KILL MY MOTHER may be found on http://www.newyorker.com/

ARC: Liveright