Note: Magda Szabo (1917 – 2007) was WINNER of the Attila Jozsef Prize in 1959 and 1972 and WINNER of the Kossuth Prize, Hungary’s top award for literature, in 1978. Translator Len Rix was WINNER won the 2006 Oxford-Weidenfeld Translation Prize for this novel, the reprint of which has been SELECTED one of the New York Times Ten Best Novels of 2015.

“Just once in my life…a door did stand before me. That door opened. It was opened by someone who defended her solitude and impotent misery so fiercely that she would have kept that door shut though a flaming roof crackled over her head. I alone had the power to make her open that lock. In turning the key she put more trust in me than she ever did in God, and in that fateful moment I believed I was godlike…We were both wrong: she who put her faith in me, and I who thought too well of myself.”—Magdushka, speaking of her servant Emerence.

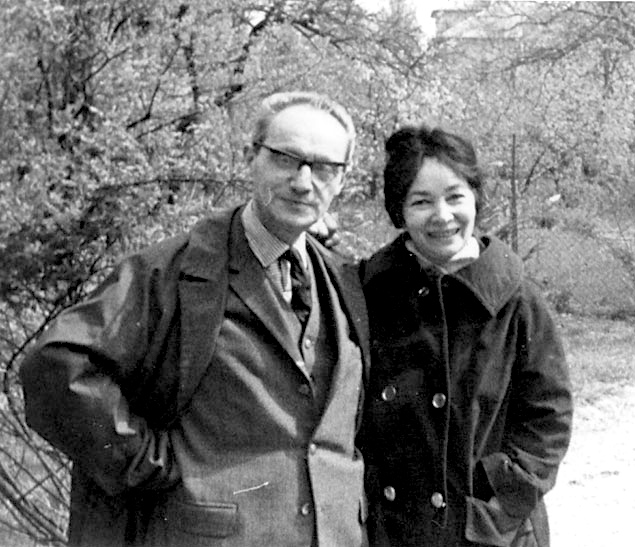

Magda Szabo and her husband, Tibor Szobotka, writer (1913 – 1982) in the garden of their home. (Photo from private collection)

Magda Szabo (1917 – 2007), one of Hungary’s most celebrated authors, lays bare her own values and her soul in The Door, a rich and intensely intimate examination of the relationship between a character named Magdushka, a writer whose point of view controls this novel, and Emerence, her housekeeper-servant. As suggested by the choice of the main character’s name and occupation, much of the story here parallels aspects obvious from the author’s own biography, and she has admitted in an interview that much of the content here is based on similar experiences from her own life. How much is actually true and how much is an elaboration becomes irrelevant once the book gets underway, though it is difficult to imagine the author recreating Magdushka’s unwavering commitment to the temperamental and prideful Emerence, her affecting sense of responsibility, and her overwhelming guilt regarding her betrayal of a secret, if she herself had never experienced similar feelings under very similar conditions.

At one point Emerence brings a used boot with a spur as a gift to Magdushka. When she does not display it prominently, Emerence angrily takes it back but leaves the spur with the garnet.

Author Szabo, born in 1914, lived through World War II, the Soviet Hungarian People’s Republic, and the Stalinist Era in the early 1950s, during which time she and her husband were writing but not publishing their books. After the revolution in 1956, censorship declined, and she published her first novel, Fresco, to great acclaim in 1958, winning the Attila Jozsef Prize in 1959. The excitement of this achievement is duplicated in The Door when Magdushka also wins her first prize, and it is this event, one of the climactic moments of the book, which allows the reader to get a sense of the late 1950s, the time period in which the action takes place. Throughout the book, Emerence is regarded as much older than Magdushka, though the real Magda Szabo, born in 1917, was only twelve years younger than the fictional Emerence, described as having been age nine in 1914. By playing with time and compressing it, however, the author achieves a greater flexibility with the action, removes it from the real chronology of Hungarian history, and focuses completely on the universal human qualities of the characters, especially Magdushka and Emerence.

Laika, the first animal to go into space. Emerence was furious at the cruelty to animals this represented but consoled herself that the “heartbeat” that was broadcast was really just an alarm clock.

In a brief opening chapter, Magdushka, now in old age, describes the continuing nightmare which has loomed over her adult life. In it she is behind the front door of her own house, unable to open it for rescuers and unable to call for help. Magdushka sees parallels between this nightmare and her experiences with Emerence at the climax of their relationship many years earlier. Since what happened then is now in the past, she knows that “none of that matters, because what happened is beyond remedy.” Magdushka has always been a religious person, even through many years of communist rule, and the absolution granted by a priest to a sinner is much too easy, she feels, considering her own abhorrence of her “crime” and her still active need to atone. She has tried to live her life “with courage, and I hope to die that way, bravely, and without lies. But for that to be, I must speak out. I killed Emerence. The fact that I was trying to save her rather than destroy her changes nothing.”

When Yuri Gagarin died in an accident in 1968, Emerence “felt no more sorry for the young man who burned up like a star than she would have for Kennedy or Martin Luther King.”

Flashing back many years to when Magdushka is in her forties, the reader shares her excitement when she publishes her first book, and with her husband is able to move to a bigger apartment. Suddenly busy with public appearances and talks, she is often gone from home, and for the first time, she must find someone to help clean the house, sweep snow from the walks in the winter, and occasionally prepare meals. When Emerence is recommended to her, she immediately contacts her, but Magdushka is unprepared when she discovers that it is not she who is interviewing Emerence, but Emerence who is interviewing her: “I don’t wash just anyone’s dirty linen,” Magdushka is informed. Full of pride and an energy which is stupefying, the complex and temperamental Emerence shares nothing about her personal life or her background. She will act thoughtfully and perform extra kindnesses for some people – if they do not specifically ask for them – as long as they do not come to her house. No one is ever allowed beyond her porch. The reader gradually learns that a man named Mr. Szloka has been buried in her garden, that she never lies down to sleep, that she is virulently anti-church, and that she has a past that is so sad that it is a wonder that she can function at all.

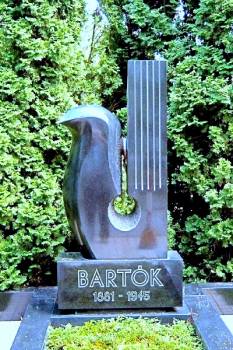

Emerence saved enough money to have a crypt built for all her relatives and herself at Farkasreti Cemetery in Budapest, the place where Bela Bartok is buried.

Through all the ups and downs of everyday life, Magdushka and Emerence forge a relationship which varies from feelings of genuine friendship to Magdushka’s occasional belief that Emerence is related to Mephisto in her perversity. As Magda Szabo, the author, drops hints throughout the novel of some of the horrors that Emerence has faced, the reader becomes sympathetic toward her even as Emerence herself scorns that kind of sympathy. Eventually, however, as the relationship between Magdushka and Emerence becomes closer and less volatile, primarily because Magdushka learns her “place,” an event occurs which challenges the very basis of friendship and trust: Emerence becomes ill but still refuses to answer the door. Magdushka, occupied with her first awards ceremony, followed by her appointment to represent the country at an international peace conference, does not realize how ill Emerence is until she returns home and goes to Emerence’s house. Only by giving many promises to obey Emerence’s directives is she able to gain admittance. What she sees breaks her heart, and she makes a decision which haunts her for the rest of her own life.

Therein lies the essence of this novel, which communicates directly with the reader because most readers would also have acted as Magdushka does. Her horrified awareness that nothing can fix the damage when actions made with the best intentions have disastrous results, brings home universal truths to the reader. The conflicts raised about the nature of promises and trust, about how much autonomy any individual should be granted to make decisions about her life, and about the nature of guilt and how and whether one must atone, come powerfully to life. The book, which repeats much of the opening chapter in its conclusion, is a brilliant commentary on the circle of life and its complexities.

ALSO by Szabo: ABIGAIL and IZA’S BALLAD

Photos, in order: The photo of Magda Szabo and her husband, Tibor Szobotka, writer (1913 – 1982) is taken in garden of their home. (Photo from private collection): http://www.literarycharacters.eu

A garnet decorates the “jinglebob” of a spur, like the one Emerence gave to Magdushka on a used boot found at a junk sale. Furious that the boot was not on display, she angrily took it back but left the spur. http://whiplashdesigns.com/

Laika, the space dog, the first animal in space. Emerence declared this to be animal cruelty and insisted that the heartbeat broadcast to the nation was really just an alarm clock. http://io9.gizmodo.com

When Yuri Gagarin died in an accident, Emerence “felt no more sorry for the young man who burned up like a star than she would have for Kennedy or Martin Luther King.” http://www.fastcompany.com

Furious that her relatives and acquaintances in her home town had not taken care of the burial site for the family, Emerence saved money to be able to build a family crypt for them and herself in the Farkasreti Cemetery in Budapest, where Bela Bartok is buried. https://commons.wikimedia.org

Helen Mirren, as Emerence, in the 2012 film of The Door is from http://www.hollywoodreporter.com