“People say that wine is grapes in a glass, but I have a different view. The grapes are gone. They are no more. What’s left are the juices, the souls of the grapes, the ghosts of the grapes. These souls, these ghosts, these are what we drink; their spirit infuses our own.”—Pierre de Benoist, nephew of Aubert de Villaine.

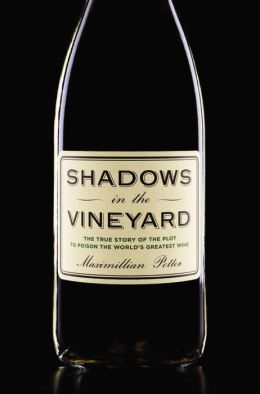

The language with which vintners, connoisseurs, and critics talk about their favorite subject often resembles religious ecstasies, making the use of sacred wine for Christian communion services seem not only appropriate but completely right. Fortunately for readers of this book, which is “the true story of the plot to poison the world’s greatest wine,” author Maximillian Potter, a journalist, takes a more secular approach to this subject, as he investigates the very real 2010 plot to poison the vines at the Domaine Romanee-Conti on the Cote d’Or, which has been in the same family for almost three hundred years. With its Pinot Noir regarded as the world’s greatest wine, and its availability extremely limited because the vineyard itself is small, the interest of sophisticated criminals in this wine is not surprising. “Bottle for bottle, vintage for vintage, Romanee-Conti is the most coveted, rarest, and thereby the most expensive wine on the planet. At auction, a single bottle of Romanee-Conti from 1945 was then fetching as much as $124,000.”

The language with which vintners, connoisseurs, and critics talk about their favorite subject often resembles religious ecstasies, making the use of sacred wine for Christian communion services seem not only appropriate but completely right. Fortunately for readers of this book, which is “the true story of the plot to poison the world’s greatest wine,” author Maximillian Potter, a journalist, takes a more secular approach to this subject, as he investigates the very real 2010 plot to poison the vines at the Domaine Romanee-Conti on the Cote d’Or, which has been in the same family for almost three hundred years. With its Pinot Noir regarded as the world’s greatest wine, and its availability extremely limited because the vineyard itself is small, the interest of sophisticated criminals in this wine is not surprising. “Bottle for bottle, vintage for vintage, Romanee-Conti is the most coveted, rarest, and thereby the most expensive wine on the planet. At auction, a single bottle of Romanee-Conti from 1945 was then fetching as much as $124,000.”

The 2010 crime within the French vineyard itself is daring, potentially devastating to the vineyard, and both complex and time-consuming to pull off, as an unknown person or persons sets out to extort a million euros from M. Aubert de Villaine, the seventy-one-year-old “Grand Monsieur” who runs the Domaine with his cousin Henri-Frederic Roch. Delivering threatening notes and a map to the Domaine, and leaving no fingerprints behind, the extortionist indicates his plan to poison the precious vines with Phylloxera vastatrix, an aphid-like insect which burrows underground and eats the plant’s roots, then creates egg-filled galls on the vine’s leaves, which eventually spread the problem as the galls break and the leaves fall. There is no cure for this infestation. When Aubert de Villaine does not act, the extortionist gives one last warning, providing more specific information and indicating that he has already drilled the bases of seven hundred vines and has already begun injecting them. He will continue to do this if his terms are not met.

Author Potter’s broad approach to this subject resembles a compilation of stories about the vineyard, its owners, and its history, jumping back to the time of Louis XV and Madame Pompadour, and then jumping forward to the present, then toggling back and forth. The author even discusses the Romans’ use of wines and the discoveries of the monks regarding viticulture during the medieval period. While some might argue that such an approach slows down the narrative about the crime itself by inserting information which is unnecessary, others will treasure the insights gained into the whole subject of wine-growing both in France in the 21st century and in Napa Valley in the 1960s. At that time, Aubert de Villaine, then in his early twenties and unsure of what he wanted to do with his life, spent time in California learning from the Paul Masson, Almaden, and Robert Mondavi vineyards, comparing his experience there with his childhood life in the vineyards at the Domaine, under the tutelage of his grandfather Edmond.

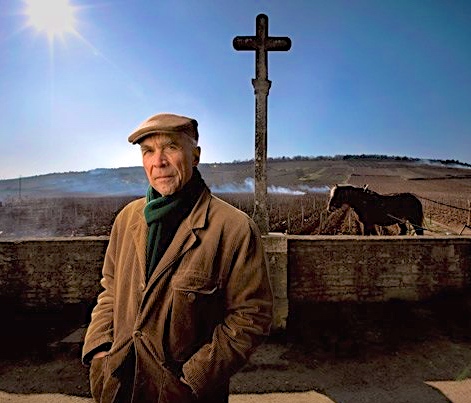

Tending the vines the traditional way – using horses instead of machines to avoid compacting the soil.

Throughout the book, Potter keeps the personalities of his subjects front and center, even within the early historical sections, giving life to a subject which might otherwise feel static. King Louis XV, Madame Pompadour, and their dislike of the Prince de Conti, an ancestor of the vineyard’s owner and cousin of Louis XV; Prince de Conti’s machinations against the king and his active support of revolution; and Prince de Conti’s purchase of a major vineyard and his withdrawal of all its wines from market, share space with a close-up view of the present extortionist as he is living in a tiny eighty square-foot cabin, half-underground, on the de Villaine property. He has disguised his hut so well that someone standing only a few feet away cannot see it, nor can helicopters or small planes. The reader soon learns that the extortionist has used a gun in crimes in the past and that he is listening to Mozart as he is drilling the vines.

The aphid-like Phylloxera vastatrix insects eat the roots of the vines, then create galls of eggs which infect the leaves and spread when they break in the wind.

The problems of Phylloxera vastatrix in vineyards in the past, from the 1850s to the 1940s, share space with the infighting in the present within the Domaine de Romanee-Conti with opinions differing between the de Villaines and the Leroys, co-owners, about the direction the vineyard should take in the twenty-first century – ultimately, quality vs. quantity. The de Villaines, as a group, prefer to stick with the tried and true old methods, while the Leroys prefer modernization. At one point, some of the Domaine’s precious wines are adulterated and sold, and a member of the Leroy family is sued because of suspicion regarding involvement in the scheme. In the vine poisoning case, the police become frustrated with their investigation after two false leads, though they are not defeated. Readers, acquainted with Inspector Laeticia Prignot and her fellow inspector Manu Pageault from the author’s character sketches of them, will empathize, while also empathizing with the sad, but beautifully elucidated family of the extortionist, a man who is also presented in detail – but without that sympathy.

Lalou Bize-Leroy, one of the partners of the Domaine from the other controlling family, argued for more modernization in the methods of growing and harvesting the grapes.

The last pages of the book tie up details and describe two unveilings of the 2010 vintage of Romanee-Conti, the year of the attack on the vines, one unveiling in New York City and one in San Francisco. Questions are raised regarding who will be the best person to succeed M. Aubert de Villaine and how soon. The author talks about his own background, his reasons for writing the book, and his opinions about wine critics with their elaborately romantic musings about wine, then describes his own first taste of Pinot Noir in the cellars of Domaine Romanee-Conti with M. Aubert. In a dramatically different style from that of the wine critics, he informs le Grand Monsieur: “This may sound crazy to you, but when I was a kid there was a candy called Pop Rocks. It was like candied sand and when you put it in your mouth, it sort of bounced around and filled your mouth. This wine is like that but it is like from heaven. It like divine, liquefied Pop Rocks that make me feel lightheaded – the kind of happiness that I felt after I first kissed my wife.”

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on http://www.thestar.com

“Le Grand Monsieur” Aubert de Villaine, outside the Domaine Romanee-Conti on the Cote d’Or. http://www.vanityfair.com/

The vines are tended the old-fashioned way (after a brief trial of the use of machinery), since the use of horses prevents the soil from becoming compacted, better for the vines. https://www.cellarit.com.au/

The Phylloxera vastatrix insects are shown here on the lower stem or vine roots. Once infected, the only “cure” is to plant new roots, impervious to these insects, and to graft new branches of the preferred vine stock to that root system. http://www.pesticide.ro/

Lalou Bize-Leroy, one of the partners of the Domaine from the other controlling family, argued for more modernization of the Domaine, something the M. Aubert opposed. http://dulwichonview.org.uk

A shelf of the various aged wines produced by Domaine Romanee-Conti: http://loudmeyell.com