Note: Originally from Prague, author Monika Zgustova translated this novel into Spanish. Julie Jones, an American, translated the Spanish version into English.

“When spring comes, look at the shining snow, the blue sky, the contrast between light and darkness which is enormous here. Now that it’s winter and the sun doesn’t come out, concentrate on the different shades of gray: some are blue gray; others are almost rose-colored. Don’t forget to look at the barbed wire and our pathetic huts as if you were taking a photograph, looking for the right shot…Even in the midst of ugliness, it’s possible to find beauty.”—Siberian shaman, speaking from a Russian prison camp, above the Arctic Circle.

When I first saw the romantic cover and title of this book, I assumed it might be some kind of imagined love story about the Russian past, maybe an epic story like War and Peace or Dr. Zhivago, only shorter.

When I first saw the romantic cover and title of this book, I assumed it might be some kind of imagined love story about the Russian past, maybe an epic story like War and Peace or Dr. Zhivago, only shorter.

Then I saw the subtitle at the bottom of the cover – “Women’s Voices from the Gulag” – and realized that the title and cover were both part of a monstrous irony. Dressed for a Dance in the Snow is a collection of nine true stories about some of Russia’s brightest and most creative women – workers, lovers, wives, and mothers who have defied life as it exists in those old romances – presenting, instead, the dark, often horrific revelations they have personally survived in the Gulags and prisons during the Stalinist years. Where the title deserves its happy image is that, with one exception, these women not only survived their near starvation and imprisonments but also came to some kind of peace regarding their torture. Ella Markman, in “A Twentieth-Century Judith,” is a pro-communist activist who opposed the “communism” of Stalin and Beria, and was sentenced to twenty-five years of hard labor. In her story, however, she is able to recognize a bright side to her imprisonment, as do other women featured here: “The Gulag, just because it’s so terrible,” she says, “is also rewarding. That extreme suffering teaches you about yourself, about the people around you, and about human beings in general.” In fact, she even goes so far as to say “I am grateful to the fate that sent me to the Gulag, because of everything I encountered and learned there.” She is not alone in that conclusion.

The author of this book, Monika Zgustova, left Czechoslovakia with her family in the mid-1970s, when the Soviets, who had retaken her country in 1968, began to persecute her linguist father. Later settling in the US, she attended college and studied Russian language, literature, and culture, as well as Eastern European cultural history, doing significant research on Russian dissident movements, and eventually teaching Russian in the US. In 2008, she traveled to Moscow and had the opportunity to attend a meeting of former prisoners of the Gulag. She was anxious to meet them and learn “how they had endured the cruel conditions of the Gulag under Stalin,” a time in which an estimated thirty million Russians were killed. Surprised by the number of men and women who appeared at the meeting, Zgustova decided she would interview only women, as they were “less documented,” and as she interviewed them, she began to understand that “what these women found in the Gulag was their hierarchy of values, at the top of which were books, and invulnerable, selfless friendship.”

The author of this book, Monika Zgustova, left Czechoslovakia with her family in the mid-1970s, when the Soviets, who had retaken her country in 1968, began to persecute her linguist father. Later settling in the US, she attended college and studied Russian language, literature, and culture, as well as Eastern European cultural history, doing significant research on Russian dissident movements, and eventually teaching Russian in the US. In 2008, she traveled to Moscow and had the opportunity to attend a meeting of former prisoners of the Gulag. She was anxious to meet them and learn “how they had endured the cruel conditions of the Gulag under Stalin,” a time in which an estimated thirty million Russians were killed. Surprised by the number of men and women who appeared at the meeting, Zgustova decided she would interview only women, as they were “less documented,” and as she interviewed them, she began to understand that “what these women found in the Gulag was their hierarchy of values, at the top of which were books, and invulnerable, selfless friendship.”

Nine of the “intelligent, sensitive, and strong women” Zgustova interviewed share their lives in this book, and in keeping with the magnitude of their suffering and the universality of their responses, the author is able to draw parallels between each interviewee and a Biblical, mythological, classical or folk hero, identified in each chapter title. The first chapter, entitled “Lot’s Wife,” is the story of Zayara Vesyolaya, whose father was shot during the great purges, and whose mother was sent to a concentration camp, simply “because she was his wife.” In their communal apartment one evening, while celebrating her sister’s academic success, Zayara herself is arrested by the police. Not allowed to bring anything with her except what she is wearing, she quickly accepts a friend’s camisole and pair of stockings and leaves home, dressed “as if going to a dance.” She ends up at Lubyanka Prison instead, then on to Novosibirsk in Siberia, where she is sentenced to spend five years. There she meets Nikolai, a charming and attractive young painter who has already served fourteen years. Later, she gets transferred to Kazakhstan and has to leave without warning, hence the title of the chapter.

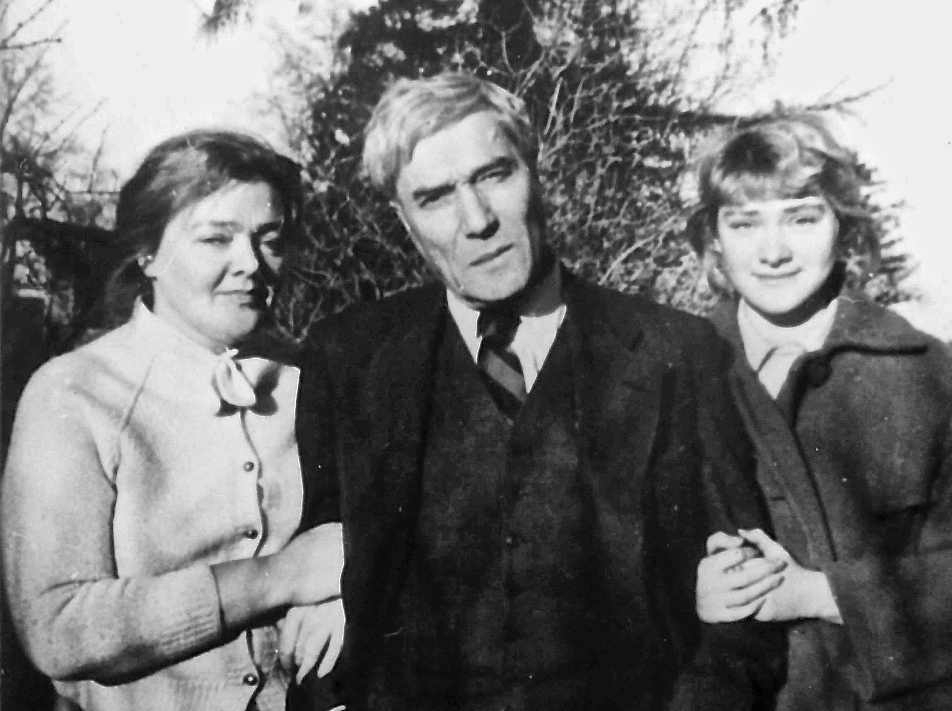

In “Penelope in Chains,” Susanna Pechuro tells of her childhood as a Jew who spoke Yiddish and the policy of anti-Semitism, a new concept to her. A number of her friends are arrested, as is Susanna herself at age seventeen, and she eventually ends up in eleven different prisons and seven work camps over the years. Lina Prokofiev, a Spanish singer who was the wife of composer Sergei Prokofiev, befriends her in one of these camps. Another character, Ella Markman, in “Twentieth Century Judith,” has saved all the correspondence between Ariadna Efron Tsevetaeva, daughter of poet Marina Tsevetaeva, and novelist Boris Pasternak, correspondence that is completely new to modern critics. Pasternak appears in these stories again in “Eurydice in the Underworld,” in which Irina Emelyanova is the speaker. Irina is the daughter of Olga Ivinskaya, Pasternak’s last love and the inspiration for Lara, in Doctor Zhivago. Olga, too, has had her time in the prison camps, and her sadistic treatment by the female head of the work brigade, who was sentenced to ten years, as opposed to Olga’s five, is emotionally offset by the behavior of the commander of the camp, who has her brought to his office one night so that she can read a long letter and notebook of poetry by Pasternak. The behavior of Pasternak’s wife Zinaida, upon Olga’s release, however, nearly ends the relationship: Ultimately, Pasternak can not live without Olga, but he can not make himself abandon his wife.

Boris Pasternak with Olga (left) and Irina (right)

Natalia Gorbanevskaya, a journalist, dissident, and poet, in “Antigone Facing the Kremlin,” tells of her experiences in 1968, set later than most of the other chapters, as the Soviets invade Czechoslovakia. The dissidents in Moscow decide that the only appropriate action is to have a demonstration, during which many are beaten and sent directly to prison. Natalia recalls that British playwright Tom Stoppard wrote a play about the demonstrators’ bravery in Red Square, and Joan Baez composed a song named “Natalia,” about Gorbanevskaya, saying, “It is because of people like Natalia Gorbanevskaya…that you and I are still alive and walking on the face of the earth.” Balancing details about the Soviets’ cruelty under Joseph Stalin against the artists and writers who risked their lives to remain true to their beliefs, this fascinating but very sad history provides new insights not only into the period but into the ability of humans to adapt to horrors. As Susanna Pechuro says, “I know that without my experience in the Gulag I wouldn’t be what I am today: a woman who is afraid of nothing…[I am] armored. I have passed the test.”

Photos. The author’s photo is appears on https://voxeurop.eu/

The photo of Zayara Vesiolaya is Photo #1 in photo section of this book, Monika Zgustova’s DRESSED FOR A DANCE IN THE SNOW.

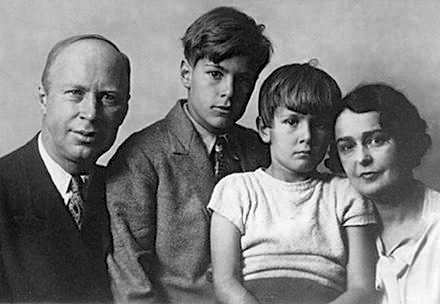

The family of composer Sergei Prokofief, with Lina on the right, is from https://en.wikipedia.org

Boris Pasternak, with his great love Olga and his daughter Irina, is from https://www.seattletimes.com

Lubyanka Prison in Moscow is now a museum: https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/lubyanka