‘Happiness,’ he said, ‘always seems nothing. It is like water; one only realizes it when it has run away’…It is the same with the evil we do; it seems nothing, just seems foolishness, cold water, while we are doing it. Otherwise, people would not do it; they would be more careful.’–Vincenzino, to Cate

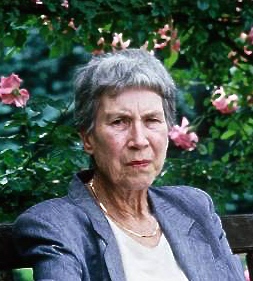

I n this newly reprinted Italian classic by Natalia Ginzburg, originally published in Italy in 1961, Elsa, an unmarried young woman of twenty-seven, realistically depicts her own life, the lives of her family, and the social scene of a small, unnamed town in Italy during and after World War II. As the only first person speaker in the novel, Elsa guides the action in three chapters, giving personal insights and a sense of honesty to the day-to-day activity of which she is part. Four other chapters, concentrating on the points of view of other characters, emerge from her parents’ generation – their prewar lives illustrating where they have started and their postwar lives revealing the effects that fascism, socialism, communism, and the partisanship of wartime have made on their domestic lives, family, and friendships. Ginzburg herself, an active anti-fascist, was a survivor of World War II in Italy, having escaped military arrest and imprisonment by using a pen name while she and her husband ran an anti-Fascist newspaper. Though her husband was violently arrested and tortured to death in 1944, leaving her to care for their three children, she soldiered on. In her dozen or so post-war novels, including this one, she remains remarkably controlled in her writing, avoiding strong flights of emotion, and the tendency to blame politics for the big issues in people’s personal lives, postwar. This allows some of her characters the kind of privacy one might allow a friend who does not care to share details of traumatic experiences.

n this newly reprinted Italian classic by Natalia Ginzburg, originally published in Italy in 1961, Elsa, an unmarried young woman of twenty-seven, realistically depicts her own life, the lives of her family, and the social scene of a small, unnamed town in Italy during and after World War II. As the only first person speaker in the novel, Elsa guides the action in three chapters, giving personal insights and a sense of honesty to the day-to-day activity of which she is part. Four other chapters, concentrating on the points of view of other characters, emerge from her parents’ generation – their prewar lives illustrating where they have started and their postwar lives revealing the effects that fascism, socialism, communism, and the partisanship of wartime have made on their domestic lives, family, and friendships. Ginzburg herself, an active anti-fascist, was a survivor of World War II in Italy, having escaped military arrest and imprisonment by using a pen name while she and her husband ran an anti-Fascist newspaper. Though her husband was violently arrested and tortured to death in 1944, leaving her to care for their three children, she soldiered on. In her dozen or so post-war novels, including this one, she remains remarkably controlled in her writing, avoiding strong flights of emotion, and the tendency to blame politics for the big issues in people’s personal lives, postwar. This allows some of her characters the kind of privacy one might allow a friend who does not care to share details of traumatic experiences.

Elsa’s tendency to cherish privacy is revealed in her three chapters, which detail her life with her mother, her family, and with Tommasino, a character whose role is not fully developed until late in the novel. Characteristically of Ginzburg, she introduces his name early – in Chapter Three – when Giuliana Bottiglia, one of Elsa’s female friends, visits, shares the romantic details of a Yul Brynner film, comments on a recent party Elsa’s family did not attend, then tries to engage Elsa in conversation about “Tommasino,” with whom Elsa was seen at night in a bar by two other young women. Giuliana persistently “leads” Elsa with hints, then gets angry because Elsa will admit and share nothing: “You do not tell me anything anymore,” Giuliana complains. “I used to be your friend,” she continues, “[Now] we talk about silly little things. I bore you, I know it.” Then the topic changes and Giuliana’s attempt to obtain gossip from Elsa is abandoned.

The remaining four chapters provide background information regarding the older generation during and after the war. Most prominent among this generation and its descendants is the De Francisci family, which still owns a chemical-spewing cloth factory, even postwar, and still employs a large number of residents including Elsa’s father, who is the accountant, and their friend Bottiglia, a lawyer, who is the manager. The De Franciscis, known locally as the “Balotta” family, answer to the nickname given to the eldest member of the family, Old Balotta, or Little Ball, a short, stout man with a big paunch, “as round as round, which overflowed above the waist of his trousers.” A socialist, Old Balotta and his family provide most of the action here – and are the source of much of the gossip – within the community. Their five children play active roles in the social life of the younger generation and are the source of information about the war and just about everything else. Gemmina, the oldest daughter, falls in love with Nebbia, and enjoys hiking in the mountains with him, and his later death in wartime echoes throughout the novel. Vincenzino, a poor student, failed his father’s goals when he majored in engineering, instead of economics, which would have helped his father in the cloth factory. His marriage to Caté is a highly detailed, personal disaster.

Mario, the third child, disappoints Old Balotta, when he goes to Munich and marries Xenia, a Russian girl, there, then returns to Italy with her. Raffaella, the fourth child, “behaved like a rowdy boy”and enjoyed playing tricks on people. Living in the mountains during the war, she helped the partisans. It is the youngest son, Tommasino, who becomes linked with Elsa, thereby connecting her life, otherwise undeveloped here, with the lives of the Balottas as they deal with the war and their escapes from the war to the countryside. Purillo, an adopted son of Old Balotta, is a fascist, but he remains loyal to his adoptive father long enough to help him physically escape danger in town, before he, too, disappears. Still others are already out of the country, including Elsa’s sister, who married and went to live in South Africa, and her brother, who is working in Venezuela.

Italian author Natalia Ginzburg (1916 – 1991), Turin, Italy, circa 1990. (Photo by Leonardo Cendamo/Getty Images)

Unusual to the point of being unique, or almost unique, Voices in the Evening deals with the growth of fascism in Italy, World War II, and the postwar conditions – big, complex subjects – but these issues become almost peripheral to the everyday gossip and personal stories on which the main characters and the community depend for their daily lives. The issue of moving from their local towns and cities for parts of the war and its aftermath is treated almost casually, with more attention paid to love and its complications, gossip, and personal tales than to the big subject of Italy during the war. By changing the focus so significantly, the author is able to gain some dark humor while developing a creeping horror of the way in which these people allow their personal issues to camouflage the dramatic changes taking place throughout the country. As one character sums it up late in the novel: “The others, all those who have lived in this village before me. It seems to me that I am only their shadow.”

ALSO by Natalia Ginzburg: THE DRY HEART and HAPPINESS, AS SUCH

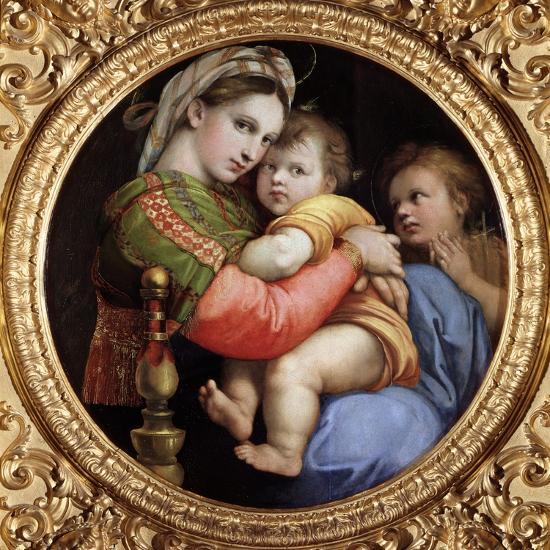

Photos. Elsa has a copy of “The Madonna of the Chair,” by Raphael in her bedroom at home. https://www.allposters.com

The old cloth factory, perhaps similar to that of Old Balotta, is from https://www.abandonedamerica.us

Many residents escaped to the Italian countryside and mountains during WW2. This is Bagnoregio. https://www.fodors.com

The author’s photo by Leonardo Cendamo is from https://www.gettyimages.com