“It’s difficult to know what you remember, is it what actually happened? Or is it the story that you’ve told and re-told and polished like a gemstone over the course of years, like something that has lustre but is as lifeless as a stone? If it weren’t for my dreams…if it weren’t for the thump I feel here in my chest, the tightness in my throat…and the trembling of my body, I wouldn’t know that what I’m telling you is true.” – China, aka Josephine Star Iron

In a remote, almost unpopulated area adjacent to Argentina’s pampas, China Iron, the main character and speaker in this small epic, grew up believing that she was “born an orphan,” never having known her mother. A light-haired baby girl, “obviously someone’s bastard child,” China was brought up as a virtual slave by a woman known as Las Negra, then married off to Martín Fierro, a gaucho-singer who won her in a card game and by whom she had two sons before reaching the age of fourteen. Now, in 1872, her husband has been conscripted by the army, along with all the other young men of the outpost, and China has decided to take off, not in search of her sometimes violent husband, but in search of a life. Leaving her babies with an elderly couple, she joins with Liz, a red-haired Scottish woman whose husband Oscar was conscripted before he could take possession of land he had planned to purchase and develop. Liz, with an oxcart, supplies, and clothing from her previous life abroad, is about to set off across the pampas in her cart to find and rescue Oscar, and she is happy to have some company.

In a remote, almost unpopulated area adjacent to Argentina’s pampas, China Iron, the main character and speaker in this small epic, grew up believing that she was “born an orphan,” never having known her mother. A light-haired baby girl, “obviously someone’s bastard child,” China was brought up as a virtual slave by a woman known as Las Negra, then married off to Martín Fierro, a gaucho-singer who won her in a card game and by whom she had two sons before reaching the age of fourteen. Now, in 1872, her husband has been conscripted by the army, along with all the other young men of the outpost, and China has decided to take off, not in search of her sometimes violent husband, but in search of a life. Leaving her babies with an elderly couple, she joins with Liz, a red-haired Scottish woman whose husband Oscar was conscripted before he could take possession of land he had planned to purchase and develop. Liz, with an oxcart, supplies, and clothing from her previous life abroad, is about to set off across the pampas in her cart to find and rescue Oscar, and she is happy to have some company.

The trip for China, an abused 14-year-old who has never left her community, offers visions of a natural world which she has never before seen or imagined – and the author recreates this in such glorious, precise detail that many readers will be stunned. The contrast between China’s reactions and those of the relatively sophisticated Liz, with her wardrobe of silk, are enhanced here by “the brightness of the light” on the pampa. As China explains it, “In [the] pampa, life is in the air. Even celestial, sometimes; far from the shack that had been my home, the world was paradise.” During their early travels across the dry land, Liz becomes a teacher for China, providing words and names for birds and animals, explaining the basics of geography, and creating some sense of security. “It was like we were secreting fine threads to make a shell or carapace,” China observes, “woven together like a kind of house made not from spider’s silk, straw, mud, or the leathery shell of a crab, but gradually formed from the loops of words and gestures.”

As she begins to gain confidence in a future she has never imagined, including a new sexual freedom she has never expected, she also starts to consider Liz to be more than just a mentor, and when Liz suggests that she cut off her hair to look like a young boy, for safety, she does so without a qualm. When Rosario, a young gaucho, appears on the pampa a bit later, accompanied by a thousand head of cattle, he seems almost as naive as China, and he joins China, her dog, and Liz on the trip to Indian country, wanting only to escape the action at the fort they have to pass before arriving at their destination. They soon learn that Rosario himself has a violent past history, the result of a terrible upbringing. As they ride, Liz’s stories of Frankenstein and Oliver Twist soon become part of China’s travels, and as Liz is an artist whose father copied the work of J. M. W. Turner, she exposes China to some of his paintings and visions of the “modern” world in works like “Snow Storm – Steam-Boat off a Harbour’s Mouth,” and “Rain, Steam, and Speed – The Great Western Railway.”

Their first hint of the future takes place when Estreya, the dog, begins barking very early in the morning, and they discover six bodies ahead – four men, a woman, and a child, murdered and left for the carrion birds. Now close to the fort, Liz gets out the clothing she has brought for the staff she expects to have at the estancia she and Oscar had planned to build, and China quickly becomes a young English “gentleman,” and Rosario becomes a proper “servant.” Before long they are at the entrance to the fort, meeting the Colonel, José Hernández.

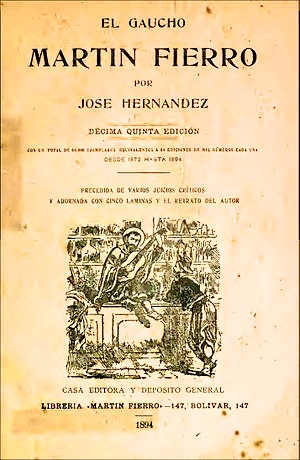

It is in this section that the label of “miniature epic” starts to take hold for foreign readers. Names which would be recognizable to Argentinians, suddenly come to life as characters here, even for those from other cultures reading this in another language. Col. Hernández, depicted as an intolerant and violent drunk, is shown to be a parody of the José Hernández who wrote the poetic epic “Martín Fierro,” which, coincidentally, also happens to be the name of China’s cruel husband. Her “Martín Fierro” has spent much of his life reviling Hernández, whom he claims stole that epic from him and continues to take undeserved credit for it. According to Hernández, “[Fierro] never appreciated what I did for him by taking some of his songs and putting them in my book. I took his voice, the voice of the voiceless…to the whole country, to the big smoke of Buenos Aires, which is always ripping us off.” China recognizes the several verses he recites, and realizes that in stealing from her husband, he also stole from her. “I decided then and there that I wouldn’t leave the fort empty-handed: justice would be done.”

It is in this section that the label of “miniature epic” starts to take hold for foreign readers. Names which would be recognizable to Argentinians, suddenly come to life as characters here, even for those from other cultures reading this in another language. Col. Hernández, depicted as an intolerant and violent drunk, is shown to be a parody of the José Hernández who wrote the poetic epic “Martín Fierro,” which, coincidentally, also happens to be the name of China’s cruel husband. Her “Martín Fierro” has spent much of his life reviling Hernández, whom he claims stole that epic from him and continues to take undeserved credit for it. According to Hernández, “[Fierro] never appreciated what I did for him by taking some of his songs and putting them in my book. I took his voice, the voice of the voiceless…to the whole country, to the big smoke of Buenos Aires, which is always ripping us off.” China recognizes the several verses he recites, and realizes that in stealing from her husband, he also stole from her. “I decided then and there that I wouldn’t leave the fort empty-handed: justice would be done.”

Author Gabriela Cabezón Cámara continues the quests of her various characters in this miniature “epic” through to their conclusions and new lives. The iteration of the Martín Fierro story is however, a dark satire, in part. The “heroes” here, while they do have goals, feel smaller-than-life, and while they do embody the values of their cultures, those cultures – of poverty, repression of women (like China, the main character here), and the growth of a nation through violence, rather than through strong cultural values – are not examples one would hold up as worthy of imitation by a nation. The line is a fine one in many places here, as this “epic” unfolds, recreating people fighting the very real problems of a very real life rather than embodying the myths and legends of the past, and the conclusion in which China and some of her companions finally find their goals fully realized is far from the glorious triumph of Odysseus and Achilles. The novel is gorgeously written in its depiction of nature and the countryside, the characters are lively, the cultural history is fascinating, and the use of the Martín Fierro “epic” history puts the lives of these characters into a far more universal perspective than a straight adventure story could come close to emulating. As China concludes from her little piece of heaven, “I wish you could see us; but no one will. We know how to leave as if vanishing into thin air….”

Photos. The wild pampas cats appear on https://www.zooborns.com Photo Credit: Bioparque M’Bopicua

J. M. W. Turner’s painting, “Rain, Steam, and Speed,” is in the National Gallery. https://en.wikipedia.org

The José Hernández portrait appears on https://en.wikipedia.org

The Martín Fierro epic, published in 1872, is shown in https://en.wikipedia.org

The author’s photo may be found on https://www.pagina12.com.ar

The photo of the carancho and the chimango may be found on https://www.pinterest.es

autobiographical novel of his early life and family in Gjirokastra, Albania, author Ismail Kadare focuses primarily on his mother, “the center of his universe” for his early years.

autobiographical novel of his early life and family in Gjirokastra, Albania, author Ismail Kadare focuses primarily on his mother, “the center of his universe” for his early years.

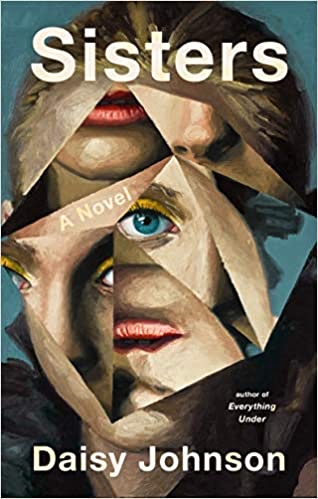

y Olson’s arresting cover art does not inspire new readers to investigate this book, the descriptions in the novel’s epigraph certainly will.

y Olson’s arresting cover art does not inspire new readers to investigate this book, the descriptions in the novel’s epigraph certainly will.

Ten pages into this novella, which Muriel Spark claimed was her favorite among all her novels, the fate of main character Lise is not in doubt. Lise will be dead before the book ends.

Ten pages into this novella, which Muriel Spark claimed was her favorite among all her novels, the fate of main character Lise is not in doubt. Lise will be dead before the book ends.

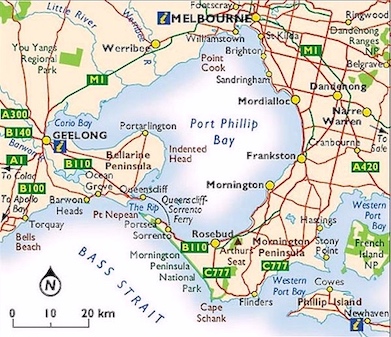

When Kate Keddie and her daughter Mia go to the Melbourne International Airport to surprise her husband John, a physician who is returning from London where he was at a conference, she is shocked when he does not show up.

When Kate Keddie and her daughter Mia go to the Melbourne International Airport to surprise her husband John, a physician who is returning from London where he was at a conference, she is shocked when he does not show up.