“I’m not asking you, reader, to step back in time. I’m asking you to stay happily where you are in the twenty-first century, looking back. We like to dream the costume drama of Edwardian times, all fine clothes, glittering jewels and clean sexy profiles – but we are less drawn to the twenty years between the wars. Understandably. Limbless ex-servicemen beg for alms on hard-hearted city streets while hysterical flappers, flat-chested, dance and drink champagne in Mayfair nightclubs.”—author’s commentary as the novel opens.

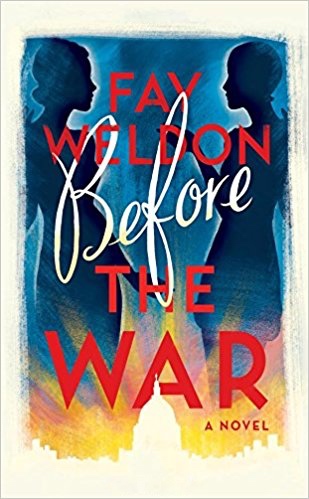

Having announced that this book will not be a “costume drama,” author Fay Weldon sets her story between 1922 and 1939, the period between the two world wars. While this is not a pure drawing room comedy, neither is it a story of postwar darkness – a story of families dealing with the deaths of their fathers and sons and the difficulties in supporting their families. Here Weldon’s characters are the elite and educated survivors from that Edwardian period, which shaped their thinking, behavior, and pocketbooks and which has left them out of touch with the real world as they now live in the war’s aftermath. Both satiric and ironic, the plot proves also to be very funny and cleverly revealing of social values. Sir Jeremy Ripple now runs a publishing house but likes to think of himself as a communist. Adela, his wife, the granddaughter of a Princess and niece of an Earl, is the money behind his company, and she still adheres to all the habits and behaviors of the upper class. Only Vivvie, their daughter, “large, ungainly, five foot eleven inches tall, and twenty years old,” seems to have much realization of how the world works – and her conclusion is that small, pretty girls are the ones lucky in love.

Having announced that this book will not be a “costume drama,” author Fay Weldon sets her story between 1922 and 1939, the period between the two world wars. While this is not a pure drawing room comedy, neither is it a story of postwar darkness – a story of families dealing with the deaths of their fathers and sons and the difficulties in supporting their families. Here Weldon’s characters are the elite and educated survivors from that Edwardian period, which shaped their thinking, behavior, and pocketbooks and which has left them out of touch with the real world as they now live in the war’s aftermath. Both satiric and ironic, the plot proves also to be very funny and cleverly revealing of social values. Sir Jeremy Ripple now runs a publishing house but likes to think of himself as a communist. Adela, his wife, the granddaughter of a Princess and niece of an Earl, is the money behind his company, and she still adheres to all the habits and behaviors of the upper class. Only Vivvie, their daughter, “large, ungainly, five foot eleven inches tall, and twenty years old,” seems to have much realization of how the world works – and her conclusion is that small, pretty girls are the ones lucky in love.

In what amounts to a twist on the typical comedy of manners, the author creates a series of absurd, even life-changing, events which these privileged people face, their only resources being those behaviors which are familiar to them. Amidst the turmoil of the story lines that evolve, the author also begins to insert herself, and by the time the “Intermission” rolls around, the reader, who is already beginning to wonder about these characters, suddenly begins to have serious questions about “the author” who is telling this story. This author/narrator claims to have known Adela well, since she “lived with her as a writer for five of her teenage years, over three novels which took place between 1900 and 1905,” up to the time when Adela was seventeen, part of Weldon’s “Love and Inheritance” series (2012 – 2013). Now, twenty more years have “passed,” and the “author” now claims to have recognized twenty-year-old Vivvie, waiting at a train station, as Adela’s daughter. As she “gets to know Vivvie” through her story, the narrator/author is surprised that Vivvie’s mother Adela has turned out to be “a selfish bitch” who nevertheless believes herself to be a good person. This author/ narrator also, somewhat naively, violates the “rules” of plotting by telling us within the first ten pages that a character with whom we will eventually develop sympathy dies, even telling us how the death occurs and how soon into the future it will take place. “Naïve” is the last word anyone would use to describe an author like Fay Weldon, and as she creates this comedy of manners, her unreliable narrator, her casual tone, and feigned naivete are a combination which proves to be both original and irresistible.

In what amounts to a twist on the typical comedy of manners, the author creates a series of absurd, even life-changing, events which these privileged people face, their only resources being those behaviors which are familiar to them. Amidst the turmoil of the story lines that evolve, the author also begins to insert herself, and by the time the “Intermission” rolls around, the reader, who is already beginning to wonder about these characters, suddenly begins to have serious questions about “the author” who is telling this story. This author/narrator claims to have known Adela well, since she “lived with her as a writer for five of her teenage years, over three novels which took place between 1900 and 1905,” up to the time when Adela was seventeen, part of Weldon’s “Love and Inheritance” series (2012 – 2013). Now, twenty more years have “passed,” and the “author” now claims to have recognized twenty-year-old Vivvie, waiting at a train station, as Adela’s daughter. As she “gets to know Vivvie” through her story, the narrator/author is surprised that Vivvie’s mother Adela has turned out to be “a selfish bitch” who nevertheless believes herself to be a good person. This author/ narrator also, somewhat naively, violates the “rules” of plotting by telling us within the first ten pages that a character with whom we will eventually develop sympathy dies, even telling us how the death occurs and how soon into the future it will take place. “Naïve” is the last word anyone would use to describe an author like Fay Weldon, and as she creates this comedy of manners, her unreliable narrator, her casual tone, and feigned naivete are a combination which proves to be both original and irresistible.

The event which begins the action for these drawing room people living in a new world is engineered by Vivvie Ripple, the twenty-year-old “giantess” daughter of Jeremy and Adela Ripple. Vivvie has decided to marry, and though she has no immediate prospects, she is smart enough to see that with her inheritance, she can probably make a kind of deal which a potential husband would find attractive. Vivvie wants to marry Sherwyn Sexton, a thirty-three-year-old Douglas Fairbanks look-alike, six inches shorter than she, and as he works at Ripple and Company, Publishers, and is anxious to get his own first novel published, she hopes that her proposal to him will appeal to his desire to quit his job so he can write full-time. Neither of them expects that this relationship, more a mutually beneficial merger than a true marriage, will be exclusive, but it will accomplish much of what they want as individuals. This not the clear-cut and simple story that it may seem, of course. Complications regarding Vivvie’s inheritance, which includes an entire town in the mountains of Bavaria; Vivvie’s relationship with her mother, who has been excluded from the will which benefits Vivvie; her parents’ own affairs and lovers; and the fact that Vivvie may be pregnant long before she should be, add to the fun of this story.

The wedding and its details are classic, as are the plans for Vivvie’s future. They are, in fact, so intriguing to one of Sherwyn’s “friends,” a writer, that he reveals them all in detail, years later, in his only novel, VICE REWARDED. Somerset Maugham attends Vivvie’s wedding, which has been planned by his decorator wife Sylvie, though the Oysters Rockefeller which were served were seen as “a fashion too far, style before content and what did one do with the little sticks once the oysters were chewed.” The honeymoon to Vivvie’s Alpine village in their new yellow three-litre Bentley Tourer, a gift from Adela and Sir Jeremy, provides time for Sherwyn to write and a way for the two to get to know each other. Gradually, the characters become more complex, and the reader soon learns just how hateful Adela can be, how ignorant Sir Jeremy is, and how venal some of the other characters are. It seems to be every man for himself and every woman for herself – and if two people are competing for the same lover, well, let the most aggressive and obvious win. Eventually, the perceived parentage of several people and the casual attitudes toward parental responsibilities among others make the comedy more pointed than lighthearted, as the author clearly feels that these issues among the upper classes are taken far too lightly.

Rothenburg ob der Tauber, a small Bavarian town, similar to the one Vivvie owns and where she spent her honeymoon.

Fay Weldon is at her peak here, and this novel is one of her most enjoyable. She makes her characters “real,” despite their reliance on family and wealth to solve their problems, and her “solutions,” especially in the conclusion, become part of a surprising grand finale. By giving dates for each of her short sections, Weldon alternates present, past, and future, to keep the story understandable, with the details presented when they are needed to advance the action and/or kept hidden to build suspense. Ultimately, the novel succeeds brilliantly as a satire of a genre – the comedy of manners – which is, by definition, partly satiric, a double whammy in terms of witty entertainment.

ALSO by Fay Weldon: CHALCOT CRESCENT, KEHUA!

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appeared in http://www.independent.co.uk/

Somerset Maugham’s portrait is from http://medicablogs.diariomedico.com/

The three-litre Bentley Tourer is found on https://commons.wikimedia.org

Rothenburg ob der Taurer is a small Bavarian town similar to the town which Vivvie owned. https://www.britannica.com/

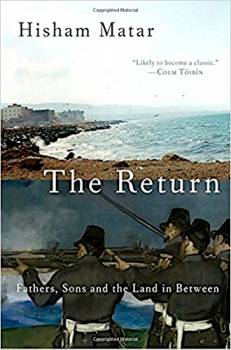

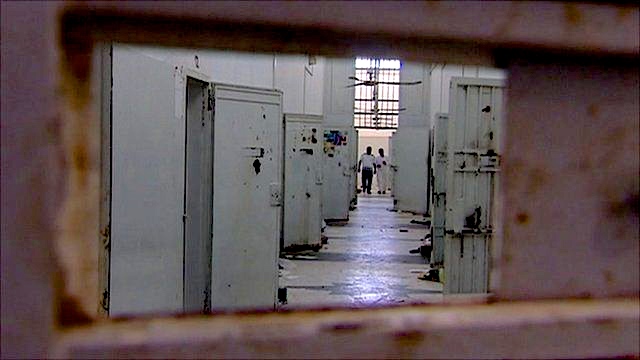

In this memoir, Hisham Matar at last tells his own story and the aftermath of his father’s disappearance and detention at the Abu-Salim Prison, one of the most vicious prisons in the world under Muammar Qaddafi in Libya. In his two novels prior to this memoir, he has dealt with some of the issues from a fictional point of view. His debut novel from 2006, In The Country of Men, tells the story of a young boy living in Tripoli, Libya, while his father works with the resistance to oust Qaddafi. With a mother who drowns her sorrows in alcohol, and a father who is often away, the boy grows up lonely and lost. Matar’s second novel,

In this memoir, Hisham Matar at last tells his own story and the aftermath of his father’s disappearance and detention at the Abu-Salim Prison, one of the most vicious prisons in the world under Muammar Qaddafi in Libya. In his two novels prior to this memoir, he has dealt with some of the issues from a fictional point of view. His debut novel from 2006, In The Country of Men, tells the story of a young boy living in Tripoli, Libya, while his father works with the resistance to oust Qaddafi. With a mother who drowns her sorrows in alcohol, and a father who is often away, the boy grows up lonely and lost. Matar’s second novel,

Junichiro Tanizaki (1886 – 1965), one of Japan’s most accomplished novelists, takes a new direction in this novel, his last. Here, in 1937, he describes the lives and cultures of a succession of Japanese house maids in a financially successful household. The novel’s time frame, 1937 – 1962, is obviously a time in which Japan faced some of its most dramatic changes, and these changes, as described by Tanizaki, were at least as dramatic sociologically as they were historically during this period. The class system was being dismantled, local languages and dialects were changing, movement from the countryside to the city and back was becoming relatively common, and a sense of independence among young women was emerging. Tanizaki saw it all, and while a previous novel, The Makioka Sisters, focused on those who lived comfortable lives, this novel focuses on those who helped make the lives of those people as comfortable as they were. These were the people who saw and dealt with the greatest changes – the maids who lived “below stairs,” as translator Michael P. Cronin describes them in his Afterword.

Junichiro Tanizaki (1886 – 1965), one of Japan’s most accomplished novelists, takes a new direction in this novel, his last. Here, in 1937, he describes the lives and cultures of a succession of Japanese house maids in a financially successful household. The novel’s time frame, 1937 – 1962, is obviously a time in which Japan faced some of its most dramatic changes, and these changes, as described by Tanizaki, were at least as dramatic sociologically as they were historically during this period. The class system was being dismantled, local languages and dialects were changing, movement from the countryside to the city and back was becoming relatively common, and a sense of independence among young women was emerging. Tanizaki saw it all, and while a previous novel, The Makioka Sisters, focused on those who lived comfortable lives, this novel focuses on those who helped make the lives of those people as comfortable as they were. These were the people who saw and dealt with the greatest changes – the maids who lived “below stairs,” as translator Michael P. Cronin describes them in his Afterword.

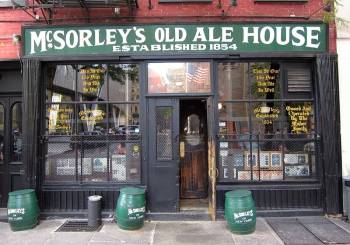

Try, for a moment, to imagine going into the attic of a house occupied by members of your family for one hundred sixty-three years. Old paintings, documents, photographs, small sculptures, war-time hats and helmets, and all manner of other memorabilia fill it from floor to ceiling, and everything there reminds you of the major events which have affected you and those closest to you. Few of us are lucky enough to have such a family attic, but McSorley’s Old Ale House in the East Village of New York City has acquired that status for thousands of customers who have visited it for over a century and a half. Established in 1854 and billed as “the oldest bar in New York city,” McSorley’s, an Irish ale house, serves only dark and light ale, never wine or hard liquor. Owned and operated by only three families during its entire history, McSorley’s has existed continuously at the same location in the East Village since its inception, and many of its employees have been there for decades.

Try, for a moment, to imagine going into the attic of a house occupied by members of your family for one hundred sixty-three years. Old paintings, documents, photographs, small sculptures, war-time hats and helmets, and all manner of other memorabilia fill it from floor to ceiling, and everything there reminds you of the major events which have affected you and those closest to you. Few of us are lucky enough to have such a family attic, but McSorley’s Old Ale House in the East Village of New York City has acquired that status for thousands of customers who have visited it for over a century and a half. Established in 1854 and billed as “the oldest bar in New York city,” McSorley’s, an Irish ale house, serves only dark and light ale, never wine or hard liquor. Owned and operated by only three families during its entire history, McSorley’s has existed continuously at the same location in the East Village since its inception, and many of its employees have been there for decades.

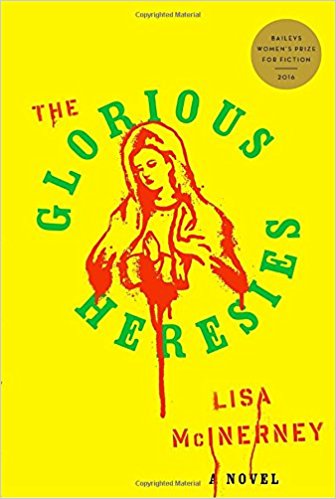

The prose of Irish debut novelist Lisa McInerney is so musical that even the horrors of characters living barebones existences in the drug-infested underworld of Cork begin to feel engaging. Here McInerney creates families and friends, enemies and predators, and lovers and their betrayers as they all try to survive the forces working against them. Their possibilities of flourishing within this fraught atmosphere are practically nil. Many characters use drugs and alcohol to make their lives more bearable, and most still have hope for a future in which they can find some level of happiness. These characters come to life – and in some cases, death – within a society which exists on its own terms, a dark society outside the dominantly Catholic mainstream, with its own rules about what is right, what is tolerated, and what requires repentance and/or punishment. Many of McInerney’s characters are aware of the ironies in their lives, as Maureen Phelan’s confession to a priest at the beginning of this review reveals, and her intentional humor in places throughout the novel provides respite for readers who might begin to weary of the sad, inner battles her characters face.

The prose of Irish debut novelist Lisa McInerney is so musical that even the horrors of characters living barebones existences in the drug-infested underworld of Cork begin to feel engaging. Here McInerney creates families and friends, enemies and predators, and lovers and their betrayers as they all try to survive the forces working against them. Their possibilities of flourishing within this fraught atmosphere are practically nil. Many characters use drugs and alcohol to make their lives more bearable, and most still have hope for a future in which they can find some level of happiness. These characters come to life – and in some cases, death – within a society which exists on its own terms, a dark society outside the dominantly Catholic mainstream, with its own rules about what is right, what is tolerated, and what requires repentance and/or punishment. Many of McInerney’s characters are aware of the ironies in their lives, as Maureen Phelan’s confession to a priest at the beginning of this review reveals, and her intentional humor in places throughout the novel provides respite for readers who might begin to weary of the sad, inner battles her characters face.