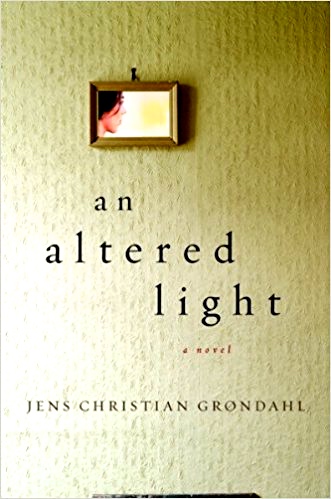

Note: This novel, published in English in 2005, was SHORTLISTED for the IMPAC Dublin Award, the biggest prize in the literary world.

“Irene Beckman is to be divorced…That’s all she knows. She’s no longer one with that life. How long has it been like that? She doesn’t know, doesn’t know any more. There’s no more knowing. There is her own life, but she doesn’t know it. Not yet. There is no ‘we.’ Her unknown self. That is what there is. And the way ahead. Unknown.”

A 56-year-old lawyer in Copenhagen, Irene Beckman discovers that after more than thirty years, she is being divorced. Her husband Martin has fallen in love with another woman, and the “light” by which she views her life has now been “altered.” Every aspect of her existence, which she has taken for granted, has changed, and she must now figure out who she really is. In the hands of Grondahl, this age-old story takes on new life as Irene reminisces about the past and how she met Martin when she was a 17-year-old au pair in Paris, tells about her parents and their relationship, mourns for her unknown twin brother who died at birth, shares stories about her children, explores her present life, and tries to plan for the future. Her “journey to self-discovery” takes on added importance when her mother, facing surgery from which she thinks she may not recover, gives Irene a journal from her own early years. In it she tells of her meeting with a Jewish cellist during the war, his escape to Sweden, and her marriage to his best friend. The secrets that pervade people’s lives—her mother’s, her own, Martin’s—Irene learns, are as much a part of their relationships and later lives as the events they share with others. Ultimately, each person’s view of selfhood, personal origins, and ultimate destiny is viewed through a combination of events kept secret and events shared.

A 56-year-old lawyer in Copenhagen, Irene Beckman discovers that after more than thirty years, she is being divorced. Her husband Martin has fallen in love with another woman, and the “light” by which she views her life has now been “altered.” Every aspect of her existence, which she has taken for granted, has changed, and she must now figure out who she really is. In the hands of Grondahl, this age-old story takes on new life as Irene reminisces about the past and how she met Martin when she was a 17-year-old au pair in Paris, tells about her parents and their relationship, mourns for her unknown twin brother who died at birth, shares stories about her children, explores her present life, and tries to plan for the future. Her “journey to self-discovery” takes on added importance when her mother, facing surgery from which she thinks she may not recover, gives Irene a journal from her own early years. In it she tells of her meeting with a Jewish cellist during the war, his escape to Sweden, and her marriage to his best friend. The secrets that pervade people’s lives—her mother’s, her own, Martin’s—Irene learns, are as much a part of their relationships and later lives as the events they share with others. Ultimately, each person’s view of selfhood, personal origins, and ultimate destiny is viewed through a combination of events kept secret and events shared.

Though the novel is introspective and analytical, it is also firmly grounded in realistic detail, which keeps Irene’s in-depth exploration of her feelings from appearing to be self-indulgent or sentimental. Dry humor is injected into the narrative through Irene’s friend Ursula, a flamboyant psychologist who gives parties in which various guests lay bare their souls. “Here everything was displayed for public deliberation—divorces, vibrators and the horrors of the world. Maybe it was yet another price [to be paid], in addition to loneliness…” Characters at these gatherings speak in jargon-filled pronouncements, with one person described as “using words you can switch on and insert in your ear.” Eventually, Irene wonders if she has “just spent the past week “overproblematizing” her own ambivalence to the point of total dysfunctionality? Instead of rolling up her sleeves and getting on with the grief process?”Ultimately, Irene’s search for truth expands beyond her immediate crisis, and she sets off on a journey to Austria and Yugoslavia and an exploration of the larger issues of identity caused by the Holocaust and its aftermath. The close, personal focus on Irene’s character broadens, and the novel becomes more plot-based, the latter action connected to Irene’s domestic problems through the theme of identity.

Though the novel is introspective and analytical, it is also firmly grounded in realistic detail, which keeps Irene’s in-depth exploration of her feelings from appearing to be self-indulgent or sentimental. Dry humor is injected into the narrative through Irene’s friend Ursula, a flamboyant psychologist who gives parties in which various guests lay bare their souls. “Here everything was displayed for public deliberation—divorces, vibrators and the horrors of the world. Maybe it was yet another price [to be paid], in addition to loneliness…” Characters at these gatherings speak in jargon-filled pronouncements, with one person described as “using words you can switch on and insert in your ear.” Eventually, Irene wonders if she has “just spent the past week “overproblematizing” her own ambivalence to the point of total dysfunctionality? Instead of rolling up her sleeves and getting on with the grief process?”Ultimately, Irene’s search for truth expands beyond her immediate crisis, and she sets off on a journey to Austria and Yugoslavia and an exploration of the larger issues of identity caused by the Holocaust and its aftermath. The close, personal focus on Irene’s character broadens, and the novel becomes more plot-based, the latter action connected to Irene’s domestic problems through the theme of identity.

Ljubljanica River, Slovenia, formerly part of Yugoslavia, to which Irene travels late in the novel.

Those who enjoy novels of self-analysis will love this one, which is leavened with dry humor but which also makes important points about how much we can expect a relationship to bear when the individuals involved do not truly know or reveal their “inner selves.” But it also makes the point that a relationship must not completely subsume the individuals, that there are private places and events which are also important, and that one must always be ready to begin again, if necessary. Every aspect of this novel, every detail, helps keep the novel focused, thematically. Irene’s jogging along the same path each morning parallels her life. The references to mass graves in the Balkans and ethnic cleansing parallel later scenes regarding the Holocaust. Her journey to Vienna and Yugoslavia parallel journeys taken by other characters at other times. When she eventually picks up a hitchhiker who does not speak her language, she feels a remarkable kinship with him. “For you everything is still undecided, for me it’s already too late,” she thinks. But then she realizes, “It is still the same beginning. Life is ceaselessly altering, and there isn’t a place in the world where we belong. Beginnings have no arrival, no final destination. Hope is homeless, but indomitable.”

ALSO by Grondahl: OFTEN I AM HAPPY

Photos, in order: The author’s photo is from https://forfatterweb.dk/

The photo of Ljubljanica River in Slovenia, formerly part of Yugoslavia, is from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ljubljana

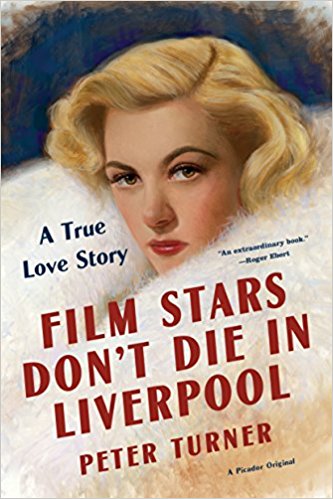

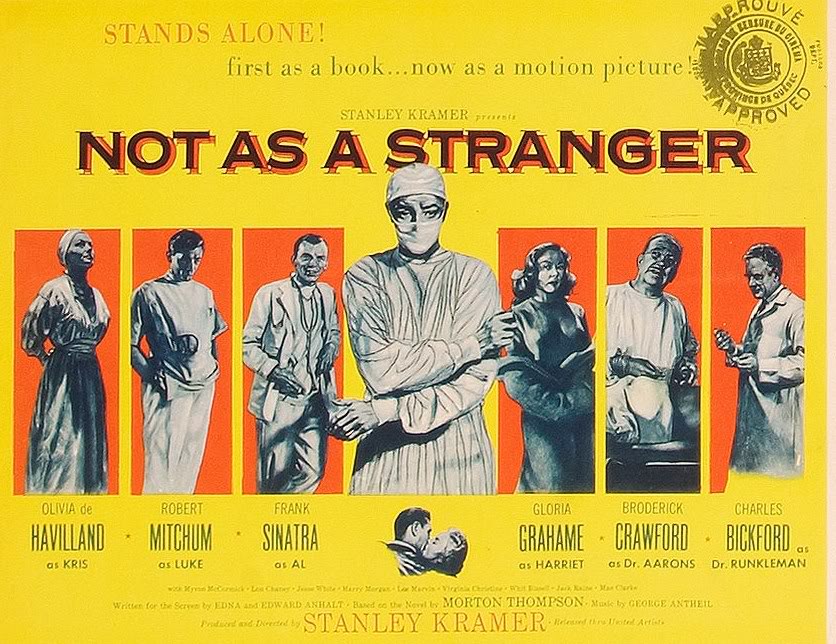

Peter Turner, who befriended Hollywood Oscar winner Gloria Grahame in 1979, was then a twenty-seven-year-old budding actor in England, and Grahame was fifty-five, a four times married American actress who had won the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress in 1952 for “The Bad and the Beautiful.” Their twenty-eight-year age difference became irrelevant as they came to know each other and Turner found he was able to keep Grahame on an even keel and to inspire her to perform her acting duties. Eventually, the two traveled and explored New York, a place new to Turner, a resident of Liverpool, as Grahame showed him the places to go and the things to do there. When, after two years, she suddenly ended all contact with him, refusing to explain anything or answer any of his messages by phone or mail, he was forced to go on with his life, his relationship with Grahame just a memory. As the novel opens, Turner is suddenly contacted by Grahame months later about getting together, and he soon discovers that she broke off her relationship with him and ended all contact because she was seriously ill and did not want to be a burden. Now, however, he realizes that she needs help – and quickly. A physician is recommending that she seek hospitalization, but she is adamantly opposed to it. Instead she wants to visit with his large family in Liverpool and stay with them until she feels better.

Peter Turner, who befriended Hollywood Oscar winner Gloria Grahame in 1979, was then a twenty-seven-year-old budding actor in England, and Grahame was fifty-five, a four times married American actress who had won the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress in 1952 for “The Bad and the Beautiful.” Their twenty-eight-year age difference became irrelevant as they came to know each other and Turner found he was able to keep Grahame on an even keel and to inspire her to perform her acting duties. Eventually, the two traveled and explored New York, a place new to Turner, a resident of Liverpool, as Grahame showed him the places to go and the things to do there. When, after two years, she suddenly ended all contact with him, refusing to explain anything or answer any of his messages by phone or mail, he was forced to go on with his life, his relationship with Grahame just a memory. As the novel opens, Turner is suddenly contacted by Grahame months later about getting together, and he soon discovers that she broke off her relationship with him and ended all contact because she was seriously ill and did not want to be a burden. Now, however, he realizes that she needs help – and quickly. A physician is recommending that she seek hospitalization, but she is adamantly opposed to it. Instead she wants to visit with his large family in Liverpool and stay with them until she feels better.

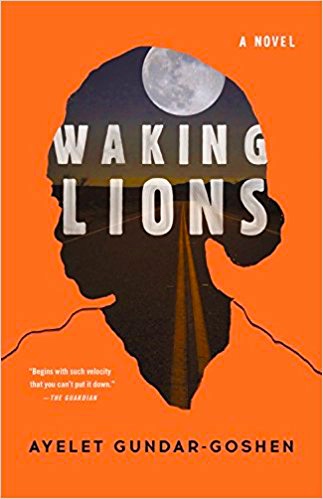

An award-winning Israeli screenwriter and WINNER of Israel’s Sapir Prize for best debut fiction, Ayelet Gundar-Goshen may find a much larger audience with this new novel, her first one to be translated into English. Critics have been busy trying to describe her work, with many calling it literary fiction because of the excellence of the prose style and the complex development of her themes. Others, however, carried away by the action and its consequences, have described it as a thriller. And, since Gundar-Goshen is a clinical psychologist using this novel to explore the ways in which some people can sometimes suppress feelings of guilt, if given enough motivation to do so, the novel may also be described as an intense psychological novel. If one considers the author’s screenwriting experience, the novel sets itself up as a possible precursor to a dramatic film – its colorful characters and the variety of populations in the exotic Israeli desert ideal for a unique film, yet another possibility for this book.

An award-winning Israeli screenwriter and WINNER of Israel’s Sapir Prize for best debut fiction, Ayelet Gundar-Goshen may find a much larger audience with this new novel, her first one to be translated into English. Critics have been busy trying to describe her work, with many calling it literary fiction because of the excellence of the prose style and the complex development of her themes. Others, however, carried away by the action and its consequences, have described it as a thriller. And, since Gundar-Goshen is a clinical psychologist using this novel to explore the ways in which some people can sometimes suppress feelings of guilt, if given enough motivation to do so, the novel may also be described as an intense psychological novel. If one considers the author’s screenwriting experience, the novel sets itself up as a possible precursor to a dramatic film – its colorful characters and the variety of populations in the exotic Israeli desert ideal for a unique film, yet another possibility for this book.

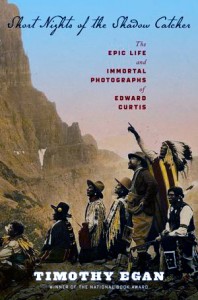

The scale, scope, and significance of this magnificent biography by National Book Award-winner Timothy Egan are only slightly eclipsed by the immense scale, scope, and significance of the work of his subject, photographer Edward Curtis (1868 – 1952). Curtis, at age twenty-eight, took his first photograph of a Native American when he did a portrait of “Princess Angeline,” an aged woman who was the last surviving child of Chief Seattle, for whom the American city was named. By 1896, when Curtis took this photo, it was illegal for Princess Angeline and other Native Americans to live within the city named for her father, and Curtis was all too aware of that sad reality. This woman was not only homeless in the traditional sense, she was bereft of the culture and belief system in which she had spent her entire life. By 1900, Native American tribes, nation-wide, had been devastated by disease and the superior weapons of the whites who wanted their land, and they now “owned” and occupied a mere two percent of the lands they had originally possessed. The small amount of land they had was in no way suited to their long cultural traditions, with the bison on which they depended for their food and skins all but wiped out and the land given to them completely unsuitable for their sustenance. Many starved to death on “their own” lands.

The scale, scope, and significance of this magnificent biography by National Book Award-winner Timothy Egan are only slightly eclipsed by the immense scale, scope, and significance of the work of his subject, photographer Edward Curtis (1868 – 1952). Curtis, at age twenty-eight, took his first photograph of a Native American when he did a portrait of “Princess Angeline,” an aged woman who was the last surviving child of Chief Seattle, for whom the American city was named. By 1896, when Curtis took this photo, it was illegal for Princess Angeline and other Native Americans to live within the city named for her father, and Curtis was all too aware of that sad reality. This woman was not only homeless in the traditional sense, she was bereft of the culture and belief system in which she had spent her entire life. By 1900, Native American tribes, nation-wide, had been devastated by disease and the superior weapons of the whites who wanted their land, and they now “owned” and occupied a mere two percent of the lands they had originally possessed. The small amount of land they had was in no way suited to their long cultural traditions, with the bison on which they depended for their food and skins all but wiped out and the land given to them completely unsuitable for their sustenance. Many starved to death on “their own” lands.