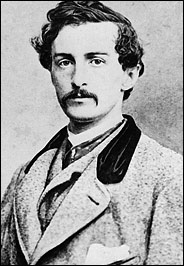

“An actor had no repose. He did not even exist, unless he kept moving, and the nature of his own existence was something he had never been able to face, even in sleep. So he had a discontinuous mind…in which nothing had either cause or consequence…The whole world was one unique event, himself, and everything [in it] a play.”—John Wilkes Booth, on Good Friday, just before the assassination.

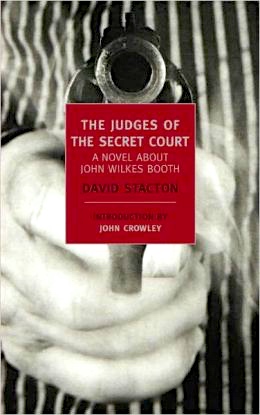

In 1963, author David Stacton was listed by Time Magazine as one of “the best American novelists of the preceding decade,” his name ensconced among luminaries like John Updike, Philip Roth, Joseph Heller, Ralph Ellison, and Bernard Malamud. Stacton’s novel of The Judges of the Secret Court, the story of the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln and its aftermath, had been published to great acclaim in 1961, when the author was only thirty-seven. Only thirty-nine when he appeared on Time’s list, Stacton had been writing serious literary and historical fiction under the name of David Stacton for more than a decade, alternating his literary novels with potboilers and pulp fiction, many of them published under the name of Bud Clifton. His well-researched historical novels ranged in subject matter and time from early Egypt under Akhenaten and Queen Nefertiti to the career of Wendell Wilkie in the early 1940s, while his potboilers ran the gamut from cowboy novels to murder mysteries set in the present. A prolific author, whose Wikipedia page lists an incredible twenty-three novels published in the eleven years between 1954 and 1965, Stacton has now, sadly, almost completely vanished from American literary history. He died in 1968, at the age of forty-four, when he was just getting started.

In 1963, author David Stacton was listed by Time Magazine as one of “the best American novelists of the preceding decade,” his name ensconced among luminaries like John Updike, Philip Roth, Joseph Heller, Ralph Ellison, and Bernard Malamud. Stacton’s novel of The Judges of the Secret Court, the story of the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln and its aftermath, had been published to great acclaim in 1961, when the author was only thirty-seven. Only thirty-nine when he appeared on Time’s list, Stacton had been writing serious literary and historical fiction under the name of David Stacton for more than a decade, alternating his literary novels with potboilers and pulp fiction, many of them published under the name of Bud Clifton. His well-researched historical novels ranged in subject matter and time from early Egypt under Akhenaten and Queen Nefertiti to the career of Wendell Wilkie in the early 1940s, while his potboilers ran the gamut from cowboy novels to murder mysteries set in the present. A prolific author, whose Wikipedia page lists an incredible twenty-three novels published in the eleven years between 1954 and 1965, Stacton has now, sadly, almost completely vanished from American literary history. He died in 1968, at the age of forty-four, when he was just getting started.

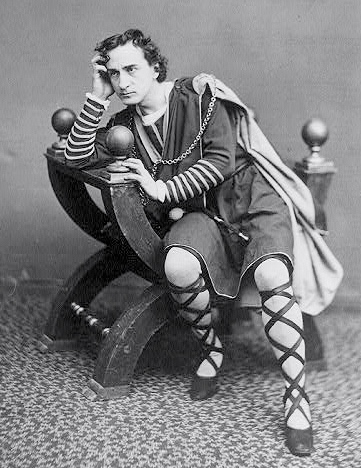

Now republished by New York Review Books Classics, Stacton’s The Judges of the Secret Court, the only one of his novels currently in print, provides readers with a sense of what they have been missing, unknowingly, all these years – and this novel is a wonder. Filled with real characters acting like real people as they deal with the aftermath of the surrender of Gen. Robert E. Lee on April 9, 1865, and the ensuing tumult, the novel shows through its characters the continuing resentments between the North and the South, as it recreates all the tensions and the growing horror of the times. Several characters share their personal points of view to give verisimilitude throughout the novel. When, just six days after Lee’s surrender, on Good Friday, twenty-seven-year-old southerner John Wilkes Booth shoots President Abraham Lincoln at Ford Theatre and escapes into the countryside, trying to reach the South where he expects to be celebrated as a hero, the reader understands why. The author provides much background for Booth, from an acting family, whose own father was mentally unbalanced – and, not incidentally, a bigamist. Wilkes Booth’s older brother Edwin, the most successful actor in the family, had been the primary support of the family, and Wilkes was clearly jealous. The author spends little time on the assassination itself, disposing with it in two sentences: “Opening the door, [Booth] slipped inside, took out his derringer, cocked it, and shot the President. The time was 10:15.”

Part II begins as Booth, with broken bones in his leg after his leap from Lincoln’s box to the stage, works his way through the countryside, trying to reach the South. As the limits of his plans become obvious, even to him, he reminds himself that he is an actor, and he must not be underestimated, no matter how injured or ill he becomes. Everyone with whom he has any contact, no matter how innocent s/he may be, however, becomes a potential co-conspirator. The newly sworn President, Andrew Johnson, tries to maintain order during the emergency, but he must jockey for power with an unusually aggressive Secretary of War, Edwin Stanton, whom we watch as he immediately establishes martial law, giving himself unprecedented powers to pursue the murderer and anyone he considers to be a “co-conspirator,” no matter how innocent. As the search for Booth evolves and continues, the author develops all the characters and their backgrounds, leading to Booth’s final realization that he is trapped. “He was going to die. This was not a performance… Did they not realize it had all been a game?”

As Part III begins, Edwin Booth, Wilkes’s brother in New York, realizes that “it was the poor people down in Washington who had to bear the brunt of [the] guilt…Even if innocent, even if spared mere human malice, they were still caught up in the inexorable malice of events…It was less a process than a parable. He could only watch.” Stanton’s craven machinations, his determination to have show trials, to deny habeas corpus ( a tactic permitted during military emergencies), and to have military trials instead of civilian trials, all affect the reader’s understanding of what has happened. The novel becomes more and more compressed and more involving as the action comes to its conclusion. Part IV is a moving commentary on military justice and the power of those in control.

The trials of several well-developed characters, innocently caught up in the swirl of events, people who have no real evidence against them and who would undoubtedly have been declared innocent if civilian trials were held, become victims of Stanton’s ambition, and readers would have to have a heart of stone not to respond to the predicament of a boarding house owner who is unwittingly caught in the action.

Ultimately, the reader is left with the thought that in this amazingly vivid saga of the aftermath of President Abraham Lincoln’s death, many of the real people involved were playing roles. The author himself had changed his name legally from Arthur Lionel Kingsley Evans to David Derek Stacton, for reasons unknown. John Wilkes Booth regarded himself as a hero, in the dramatic sense, after his assassination of the President, and was surprised when there was no great, climactic outpouring of support for him. President Andrew Johnson inspires sympathy, especially when the extent of Sec. of War Edwin Stanton’s machinations are revealed, and Stanton ultimately becomes even more of a villain than Wilkes Booth in this real-life drama. The author is careful to keep his well-researched details accurate, and the only “fudging” of the facts that I found came with Edwin Booth’s desire to keep a portrait of John Wilkes Booth by John Singer Sargent in his apartment after Wilkes’s death. The only portrait I have found of Booth by John Singer Sargent is actually a portrait of Edwin Booth himself, not of his brother. Sensitive and well-researched, this is a do-not-miss historical novel.

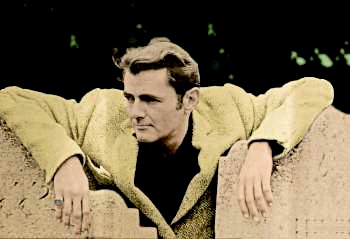

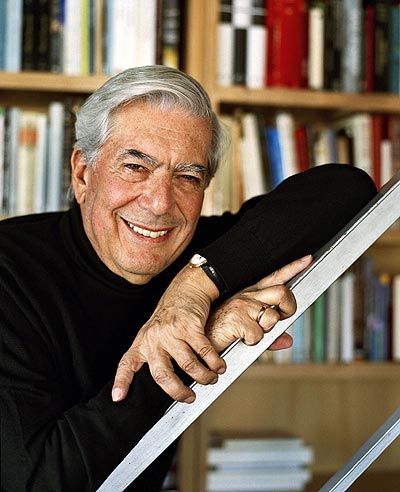

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on http://richard-t-kelly.blogspot.com/

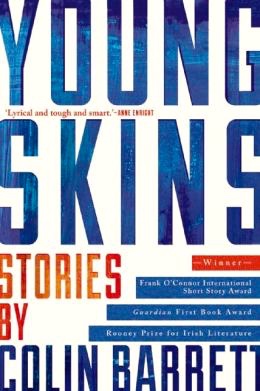

John Wilkes Booth’s photo is from http://www.nytimes.com

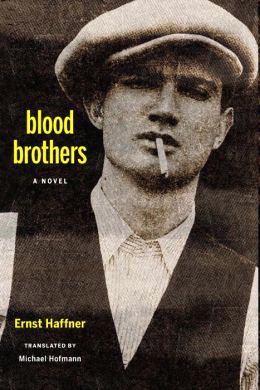

Edwin Booth, as Hamlet, is shown on http://en.wikipedia.org

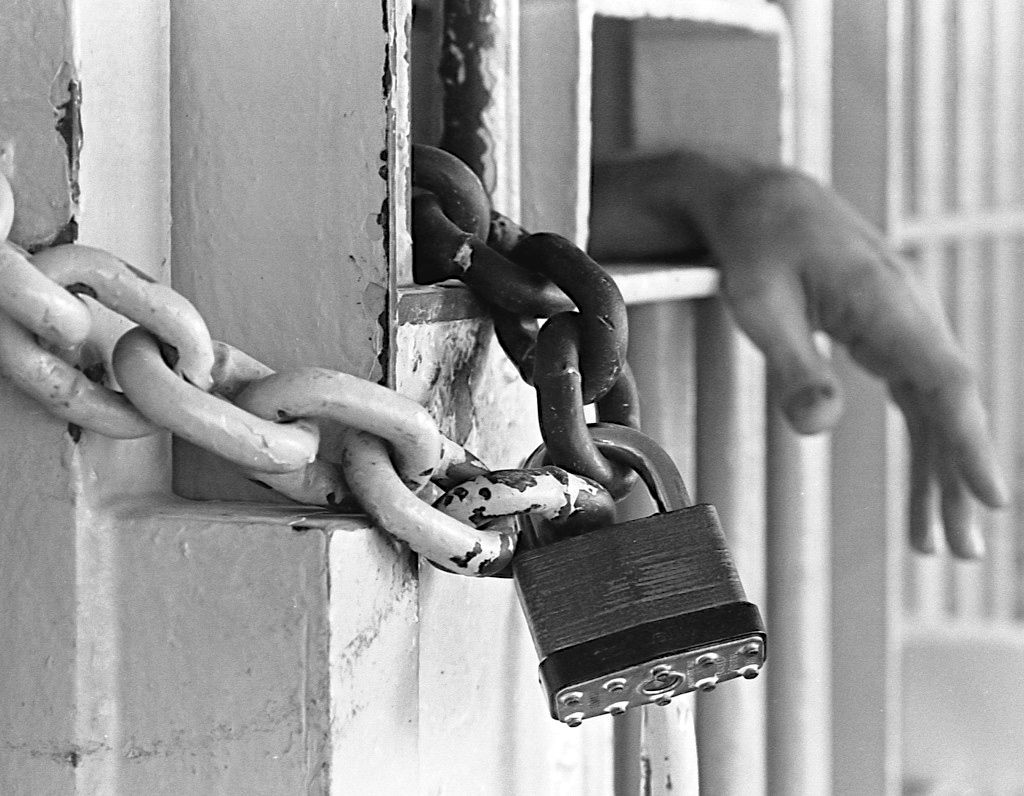

The Ford Theatre, Presidential Box, appears on http://www.nytimes.com